Comanche Nation and "Manifest Destiny": A Guide for Pre-Service Teachers

What is it?

“Manifest Destiny” — the idea that the U.S.-Americans had a religious certainty that would settle the breadth of the North American continent from coast to coast — has become a kind of shorthand for explaining the expansion of the United States. This notion has also been reinforced by many U.S. History textbooks. The reality, as is often the case with history, is quite a bit more complicated. This guide provides resources to help teachers support students as they consider Manifest Destiny more critically. Not only did territorial expansion have many causes and motivations, it was not destined in any sense.

Key Points

- The activities outlined here will take one 90-minute period or two 45-minute periods. It is appropriate for a high school U.S. history classroom, but can be modified for a variety of learners.

- Students will analyze, interpret, and evaluate primary sources.

- Students will learn to critically analyze the term "Manifest Destiny" and learn more about the history of Comanche people in the American Southwest.

Manifest Destiny in Textbooks

Many U.S. history textbooks frame the territorial expansion of the United States before the Civil War using the idea of “Manifest Destiny.” For example, in McGraw Hill’s United States History and Geography Unit 7 that covers 1820-1848 is titled “Manifest Destiny.” The unit also presents the expansion of the United States as more or less inevitable rather than a result of specific choices made by people in the past, thereby reinforcing rather than critiquing the premise of Manifest Destiny. When Native Americans are mentioned in the unit, they tend to be portrayed as an obstacle to this process. Teachers can encourage students to question the idea of Manifest Destiny and to reconsider how this narrative is being framed by their textbook by engaging with sources and historical scholarship that presents a more complex picture.

In the Classroom

Warm Up - Reframing Manifest Destiny

To encourage students to question the way the textbook frames the territorial expansion of the United States as Manifest Destiny provide the two images linked below for student to compare:

Image one: https://www.loc.gov/item/97507547/

Image two: https://iltf.org/get-involved/

The first image, the 1872 painting American Progress by John Gast, will likely already be familiar to students as it is used in many textbooks often in the same chapter that deals with “Manifest Destiny”. The second image is from the web page of a Native land rights advocacy organization the Indian Land Tenure Foundation. Titled “Reversing Manifest Destiny” it explains the mission of the organization while also commenting on Gast’s painting and the concept of Manifest Destiny. While students examine these images have them consider the following questions:

- What similarities do you notice between the two images?

- What differences do you notice?

- What story do you think each image is trying to tell?

- Why do you think the Indian Land Tenure Foundation decided to use an image based on Gast’s painting?

Comanche Nation in the Southwest

To better understand this period in American history, students can explore the history of Indigenous people who were already living in the West at the time “Manifest Destiny” was first introduced. In 1845, when columnist John O’Sullivan coined “Manifest Destiny,” a large part of the West was controlled by the politically and economically formidable Comanche, which actively thwarted expansion efforts on multiple fronts. One historian, Pekka Hämäläinen, even goes as far as calling the Comanches an “empire”. Hämäläinen writes, “For a century, roughly from 1750 to 1850, the Comanches were the dominant people in the Southwest, and they manipulated and exploited the colonial outposts in New Mexico, Texas, Louisiana, and northern Mexico to increase their safety, prosperity, and power.”

It is important to note that not all historians agree with Hämäläinen’s argument and reject the idea that Comanches or any other Indian groups constituted an “empire” at this time. Indigenous historians including Ned Blackhawk and Jameson Sweet and scholar Delphine Red Shirt argue that using the term “empire” distorts Indigenous history and culture and does not properly account for the effects of U.S. colonialism on Indigenous communities. Sweet wrote specifically that “Forcing the ‘empire’ label onto the Comanche was inaccurate and misguided”.

So whether there was a Comanche Empire is a topic of debate among historians, but the consensus among historians is that the Comanche were a formidable power in the American Southwest. This is not the impression that readers would get from U.S. history textbooks, however. In the McGraw Hill textbook, a small section deals with Native Americans and then only focuses on the Northern Plains. Meanwhile in three other sections titled “The Hispanic Southwest,” “Independence for Texas,” and “The War With Mexico,” the Comanches are mentioned only in passing and only in the context of attacks on white settlements. In both these instances, the Comanches are mentioned along with the Apache, so no independent treatment is provided for students about this group that shaped the Southwest for over a century.

Source Activities

Source Activity 1: Comanche Strategy

The Comanches mastered a divide and conquer style of politics and consistently played their rivals against each other. After warring on and off with the Spanish colony of New Mexico in the 1770s and 1780s, for example, the western Comanche leader, Ecueracapa, signed a peace treaty with the military governor of New Mexico, Juan Batista de Anza in 1786. As part of the treaty, the Comanche joined forces with Spain to attack their mutual rivals the Apaches in New Mexico. The results of one such battle are depicted in the source below.

Primary Source #1

[Comanche pictograph map of the Battle of Sierra Blanca, 1787]. | Library of Congress

https://www.loc.gov/item/2014590059/

It is important for historians of Indigenous people to use sources created by the Indigenous people themselves whenever possible. This map is one such source. The map was drawn after the battle by a Comanche participant and then it was sent to Governor Anza as the official record of the altercation. The key below the map, the letters A-G with Spanish text, was added by Spanish officials to interpret the map. Together they relate how many Comanche warriors were involved in the battle, how many on each side were killed, and how many people and horses were captured. Anza certified the document himself — signing and dating the document July 30, 1787 on the bottom.

The source is also significant for being a rare example of a source created by a Comanche from this period that has survived to the present day.

When using this map to students teachers can ask them to consider what this source created by Comanche people can tell us about the Comanche. Remind students to keep in mind that the source provides only the information that this group of Comanches wanted the government of Mexico to know.

Questions for students to consider:

- Why do you think the Comanches recorded this information and sent it to the governor of Mexico?

- How might the Comanches stand to benefit from the result of this battle?

- This map was created in 1787, one year before the U.S. Constitution was ratified and over 50 years before “Manifest Destiny” was first used. In what ways does this source make us reconsider what was happening in the American West at this time?

Source activity 2: Geography

By the 1840s, Comanchería, as the territory the Comanches controlled was called, stretched from Sante Fe in the West to San Antonio in the East. In the North, it stretched to approximately the Arkansas river in the North and in the South to the Pecos river. While powerful, the Comanche also remained “hidden” in a sense. The Comanches allowed and even sometimes encouraged settlements in their territory, but then also gained economically from those territories through raids and trade. Thus maps of the period tended to downplay the range of territory that the Comanche controlled.

Primary Source #2:

A new map of Texas, Oregon and California. 1846 https://www.loc.gov/item/00561203/.

For students to gain a better understanding of the geography of the Comanche influence in the Southwest, have them analyze this map. So that the students can zoom in on parts of the map this activity would work best on a computer - either as a whole class with the map projected on a screen or individually or in pairs with personal laptops or tablets.

First, draw their attention to the area shaded green and labeled “Texas” in the bottom part of the map. Zoom in or have students zoom in and examine this area closely. The Comanche controlled region at the time the map was made extended roughly to the following:

Eastern border - Warrenton on the Red River

Western border - Santa Fe in the West

Northern border - Arkansas River

Southern Border - Pecos River

Key questions:

- What evidence is on the map that the Comanches lived in this region?

- Would they conclude from that map that the Comanches controlled the territory? Why or why not?

- Students could additionally find the same area on a map in the textbook from this chapter - Are the Comanches are mentioned at all?

Source Activity 3: Trade Network and Economic Power

The Comanche’s power in the Southwest was fueled by a vast trade network that connected various American markets. This trade network featured a supply chain that provided horses and mules to the growing Euro-American settlements in Missouri, Arkansans, Illinois, Kentucky, and Tennessee. In addition to livestock, the Comanche traded bison hides from animals they hunted on the prairie which were highly sought after by buyers in cities on the east coast of the United States. In addition to these exports, the Comanche imported goods from all over the continent. Staples like maize from New Mexico, molasses from New Orleans, and coffee and wheat flour from the United States. Blankets were imported from Navajo country and metal goods such as kettles, pans, and knives came from eastern U.S. cities. Vast supplies of weapons too entered Comancheria in the form of lead, powder, and muskets which further bolstered the Comanches ability to conduct raids into Mexico and Texas.

A key part of this trading network and a key part of the Comanches success overall was the ability to acquire and trade horses. To give students a sense of how horses fit into the culture of the Comanche and other Southern Plains groups have them examine this collection of sources from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian https://americanindian.si.edu/exhibitions/horsenation/trading.html

Questions to consider about these sources:

Choose one of the sources in the NMAI gallery to examine in detail

- What purpose did the object serve?

- What details do you notice?

- What evidence is there that this object took a long time to create?

- What evidence is there that this object took expertise to create?

- What do these sources tell us about how the Comanches along with the Pueblo, Navajo, Apache, Ute, and Shoshone valued horses?

In discussing this vast Comanche trading network with students, teachers could return to the 1846 map (Primary Source #2) or any other map from their textbook and see if they can locate Bent’s Fort. On the 1846 map it is obscured by shading but it can be found on the Arkansas River on the northern edge of Comanchería. Bent’s Fort was a U.S. military fort but it also served as a trade hub for the trade goods listed above coming into and flowing out of Comanchería. Students could then find locations like New Orleans, New Mexico, Navajo country to appreciate the reach and extent of this trade.

Along with examining the map and considering the trade that centered at Bent’s Fort, Students could also examine a drawing of the fort itself:

Drawing of Bent’s Fort, 1859 https://www.loc.gov/item/2004661632/

Land Theft and Extermination of the American Bison

The United States did eventually expand into Comanchería, but this expansion could not be called Manifest Destiny. Instead it was a drawn out process that met with fierce resistance from the Comanche and relied on the purposeful extermination of almost an entire species of animal. After the end of the Civil War in 1865, the U.S. government turned its attention to settling the west and devoted increased military resources to accomplish this goal. To open up the land for settlers, the U.S. planned to designate tracts of land as reservations for Native Americans to live on. Another goal of this policy was to assimilate Native Americans into white-U.S. culture and to end the practices associated with hunting and religious practices.

One group of reservations would be for Indians of the northern plains, the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, Northern Arapahoes and Crows, and would be located in the Black Hills of the Dakota Territory. Another group of reservations would be for the Indians of the Southwest and southern plains, including the Comanches, Kiowas, Naishans, Southern Cheyenne, and Southern Arapahoes, and would be located in what is today western Oklahoma.

In 1867, the Medicine Lodge Treaty officially created the southern reservations. The Comanches and several allied groups agreed to the terms but had their own interpretation of what those terms meant. The treaty also granted bison hunting rights to the Comanche in the region south of the Arkansas River. These hunting grounds extended beyond the reservation tract and to the Comanches thinking that meant that this land had not been ceded. Comanche made use of the reservation but only seasonally — raiding and hunting in the spring, summer, and fall and then returning to the reservation in the winter. Thus while the U.S. government sought to end the way of life of the Comanche and other southern plains Native people, the Comanches instead incorporated the reservation into their seasonal migration. With bison to hunt the Comanche did not need the support of the U.S. government that the reservation represented.

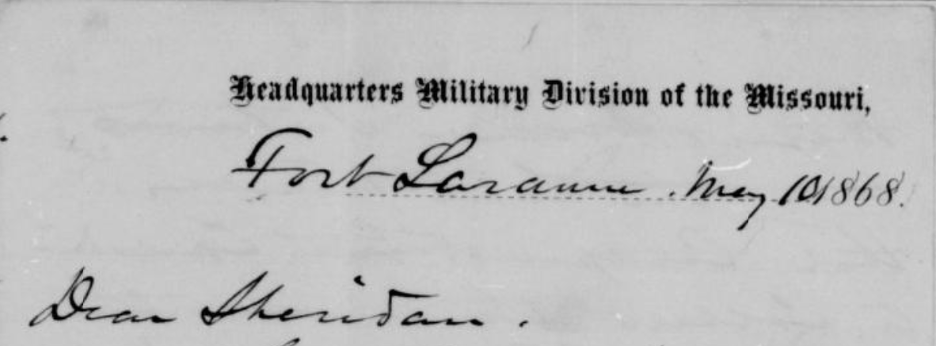

Unable to control the Comanches using military force, the U.S. government’s response was to eliminate their means of support: the bison. Beginning in 1868, under the direction of Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman and his subordinate Gen. Philip Sheridan, the U.S. Army actively engaged in the mass killing of bison and encouraged private hunters by organizing hunting excursions and even supplying firearms when requested

.

Primary Source #4

Sherman to Sheridan, 10 May 1868, The Papers of Philip H . Sheridan, microfilm reel no. 17, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC (hereafter Sheridan Papers)

https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss39768.017_0007_0246/?sp=4

https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss39768.017_0007_0246/?sp=5

https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss39768.017_0007_0246/?sp=6

By some estimates, this campaign resulted in the killing of 31 million American bison between 1868 and 1881. Some were harvested for their valuable hides or meat, but many were just left to rot. The purpose was to deny the resource to the Native people. Thus deprived of their primary source of food and their most valuable trade good, the Comanche were unable to mount as formidable a military force as they had in the pre-Civil War period. As historian David D. Smits argues: “In the end, the frontier army’s well-calculated policy of destroying the buffalo in order to conquer the Plains Indians proved more effective than any other weapon in its arsenal.” Under the charismatic leadership of Quanah Parker, however, the Comanches continued to hold out against efforts by the U.S. Army to confine them to the reservation. Not until September 28, 1874 with the Battle of Palo Duro Canyon, part of what was known as the Red River Wars, were the Comanche forces defeated.

Born in 1845 to a Comanche leader (Peta Nocona) and an Anglo American mother (Cynthia Ann Parker), Quanah Parker was not only an effective and resourceful military leader but was also representative of the Comanche’s flexible understanding of race and tendency to incorporate captives into their society.

Primary Source #5

[Quanah Parker, Comanche Indian Chief, full-length portrait, standing, facing front, holding feathers, in front of tepee] | Library of Congress

https://www.loc.gov/item/89714963/

Questions to ask about this source:

- Why do you think Quanah Parker chose to present herself in traditional Native clothing.

- What might have been his reasons for this choice?

Comanche Nation Today

Despite the efforts of the U.S. government to undermine the Comanches, the Comanche Nation still exists today with approximately 17,000 enrolled tribal members. The Comanche Nation Constitution ratified in 1966, declares that the mission of the Comanche Nation is to:

“1. To define, establish and safe guard the rights, powers and privileges of the tribe and its members.

2. To improve the economic, moral, educational and health status of its members and to cooperate with and seek the assistance of the United States in carrying out mutual programs to accomplish these purposes by all possible means.

3. To promote in other ways the common well-being of the tribe and its membership.

The headquarters for the Comanche Nation is located in southwestern Oklahoma in a town called Lawton. In 2007, the Comanche National Museum and Cultural Center opened in Lawton. https://www.comanchemuseum.com/index.html

Manifest Destiny - Additional Approaches

Other sources to explore

An important source for understanding the history of Indigenous people are the collected stories passed down from ancestors. A Comanche man, Francis Joseph Attocknie, collected the stories of his grandfather and great grandmother passed their ancestor, Ten Bears, who was a Yamparika Comanche leader who lived from 1790 to 1872. Attocknie compiled these stories in the book The Life of Ten Bears: Comanche Historical Narratives. Attocknie writes of these collected stories:

The greatest and most reliable source of Comanche history was the enjoyable, time-passing evening sessions of storytelling by wise, ancient, and loving grandfathers and grandmothers. Those story sessions entertained as well as taught. Sometimes there would be more than one person holding the session; a visiting ancient one might collaborate or add bits here and there, or just audibly agree to the account as it unwound and held spellbound its listeners, both young and adult. Repetition never bored the enthralled listeners. In fact, the young, especially, often asked for repeats of favorite accounts of certain events or stories. These stories, too, often had musical tones as the storyteller interspersed the accounts with an appropriate song that had a place in the telling of an account.

Other lessons

“How Did Six Different Native Nations Try to Avoid Removal?” National Museum of the American Indian

An excellent lesson plan about the strategies that six American Indian nations tried to avoid removal from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. Afterwards students select a case study and closely examine the sources that tell a story of removal.

https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/removal#titlePage

The Stanford History Education Group (SHEG) has put together a great activity with primary sources that demonstrates the multiple motivations behind expansion as well as sources from those at the time who opposed this expansion. https://sheg.stanford.edu/history-lessons/manifest-destiny

Other approaches

In addition to incorporating an activity on the Comanches, there are a number of other ways teachers can help students understand the complexity behind Manifest Destiny and territorial expansion. Students can, for example, consider the writings of John L. O’Sullivan, the columnist who coined the term Manifest Destiny, in their historical context. O’Sullivan was an enthusiastic advocate of westward expansion, and used Manifest Destiny in a column advocating for the United States to annex the then independent republic of Texas in 1845. The very fact that O’Sullivan was trying to make the case for annexation implies strongly that not everyone agreed with his position. Clearly not everyone in the United States at the time felt that the United States had a moral obligation to expand. O’Sullivan himself gives more than one rationale for expanding, noting that a U.S. that spread across the continent would engender the “immense utility to the commerce of the world” which hints that there were also economic reasons to support expansion.

Teachers might introduce a unit on Manifest Destiny by playing this brief audio clip (~5 minutes), a group of historians explain what Manifest Destiny means and how they approach the topic with students. https://www.r2studios.org/show/consolation-prize/season-2-trailer-what-is-manifest-destiny/

The terminology might be difficult for some students, but even if not used in the classroom the clip is helpful for teachers looking for a brief but scholarly perspective on Manifest Destiny.

Teachers could also have students search Manifest Destiny on Google Books Ngram Viewer <https://books.google.com/ngrams/>. This search engine charts the frequencies of any word or phrase using a yearly count found in printed sources that have been digitized by Google. The graph shows that the term was used increasingly in the 1840s through the 1850s. Teachers could ask students why they think that was the case. It seems to suggest that rather than describing that the Manifest Destiny served as a justification after the expansion occurred. https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=manifest+destiny&year_start=1800&year_end=2019&corpus=en-2019&smoothing=3

General Tips for Teaching Controversial Subjects

- Center activities on primary sources. Primary sources are tangible evidence that allow students to engage directly with history. These primary sources in particular were preserved and digitized by the Library of Congress because they were deemed important to the history of the United States.

- Discussion and analysis of these sources can be wide ranging, but within each class those discussions can always be turned back to the source itself.

- The sources are also, by definition, only pieces of a puzzle. They bring us closer to understanding the past but there is always room for doubt and uncertainty.

- Questions, Observations, and Reflections should come from students. These are primarily student-directed learning activities. It is the instructor's role to create a space for inquiry and empower students to drive the inquiry.

- It may help to remind students at the outset that it is normal for different individuals to come to different conclusions, even when we are looking at the same sources. Further, it would be strange if we all agreed completely on our interpretations. This can normalize the strong reactions that can come up and enables educators to discuss the goal of historical research, which is to hopefully go beyond the realm of individual perspective to access a fuller understanding of the past that takes multiple perspectives into account.

- Teaching historical topics that involve violence and other trauma can be traumatic for some students as well. Providing students with previews of what content will be covered and space to process their emotions can be helpful. The following video series from the University of Minnesota contains further tips for teaching potentially traumatic topics: https://extension.umn.edu/trauma-and-healing/historical-trauma-and-cultural-healing.