Schooled in Court Cases

The U.S. Supreme Court both looks to and sets precedents in handing down decisions that affect the fabric of American life and ideals—including the workings of U.S. schools. Match these descriptions of U.S. Supreme Court rulings on schools with the names of the cases.

1. Runyon v. McCrary, 1976: Private schools may not discriminate on the basis of race.

The Court decided that the 1871 Civil Rights Act gave the federal government power to override private as well as state-supported racial discrimination.

2. Epperson v. Arkansas, 1968: Prohibiting the teaching of evolution in public schools is unconstitutional.

The Court took on the case despite the fact that the state of Arkansas had never attempted to enforce its statute against teaching evolution.

3. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 1954: Racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional.

State laws that had set up "separate but equal" schools for black students and white students were overturned, because such schools were "inherently unequal," and so violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

4. Meyer v. Nebraska, 1923: Prohibiting the teaching of foreign languages in grade schools is unconstitutional.

A Nebraska law had prohibited the teaching (before high school) of any subject to any child in any language other than English. The plaintiff was a parochial school teacher who had taught German to one of his students.

5. Abington School District v. Schempp, 1963: Requiring the reading of Bible verses in public school classrooms is unconstitutional.

A Pennsylvania State law had required public schools to open each day with a reading, without comment, of 10 Bible verses.

6. Pierce v. Society of Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, 1925: Parents may send their children to private schools rather than public schools.

The State of Oregon had been on the verge of forcing all children to attend public schools in order to encourage immigrants' assimilation.

7. Engel v. Vitale, 1962: Requiring the recitation in public schools of an official school prayer is unconstitutional.

A Hyde Park, New York, school had opened each school day with a prayer addressed "Almighty God," which the Court held violated the Establishment Clause of the 1st Amendment (extended to the individual states by the 14th Amendment).

8. United States v. Virginia, 1996: Excluding either gender from any public school is unconstitutional.

The Court ruled that the Virginia Military Institute had not demonstrated a persuasive reason for excluding women, and so violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

9. Wisconsin v. Yoder, 1972: Parents may refuse to send their children to school after 8th grade if it violates their religious beliefs.

Amish parents had taken their children out of school after 8th grade, for religious reasons, and state authorities had attempted to force them to attend high school.

10. Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, 1969: Student protest is protected by 1st Amendment freedom of speech.

The protest in question was students' wearing of black armbands with peace symbols during the Vietnam War.

For more on major U.S. Supreme Court cases, try a search in our Website Reviews, using the topic "Legal History" or the keywords "Supreme Court." Search results will include websites like Oyez: U.S. Supreme Court Multimedia, which features audio files, abstracts, transcriptions of oral arguments, and written opinions covering more than 3,300 Supreme Court cases, and Landmark Supreme Court Cases, which looks at 17 major court cases from a teaching perspective.

For more on major U.S. Supreme Court cases, try a search in our Website Reviews, using the topic "Legal History" or the keywords "Supreme Court." Search results will include websites like Oyez: U.S. Supreme Court Multimedia, which features audio files, abstracts, transcriptions of oral arguments, and written opinions covering more than 3,300 Supreme Court cases, and Landmark Supreme Court Cases, which looks at 17 major court cases from a teaching perspective.

Or search by individual court case. A search for keywords "Brown Board of Education" using our general search (see the top righthand corner of the screen) produces websites (such as the University of Michigan's Digital Archive: Brown v. Board of Education), online history lectures, museums and historic sites, and other related resources.

Also check out our blog's roundups of resources on the Supreme Court: Our Courts Especially for Middle School Students and The Supreme Court: Connections Between Past and Present.

- "The old Supreme Court chambers in the Capitol building," Harper's Weekly, May 21 (1910): 8.

- Oyez Project, Oyez: U. S. Supreme Court Media (accessed August 27, 2009).

- Supreme Court Historical Society (accessed August 27, 2009).

Oysters became a high-demand source of protein and nutrition following the Civil War. With the rise of industry and of shipping by rail, canneries and corporate oyster farming operations sprang up on both coasts, eager to supply the working class, and anyone else who wanted the tasty shellfish, with oysters shipped live or canned. In San Francisco, a center of oyster piracy, the boom years of the oyster industry corresponded, unsurprisingly, with those of the oyster industry—both took off in 1870, as the state began allowing major oyster farming operations to purchase the rights to underwater bay "land" (traditionally common property), and petered off in the 1920s, as silt and pollution disrupted the bay's ecosystem.

Oysters became a high-demand source of protein and nutrition following the Civil War. With the rise of industry and of shipping by rail, canneries and corporate oyster farming operations sprang up on both coasts, eager to supply the working class, and anyone else who wanted the tasty shellfish, with oysters shipped live or canned. In San Francisco, a center of oyster piracy, the boom years of the oyster industry corresponded, unsurprisingly, with those of the oyster industry—both took off in 1870, as the state began allowing major oyster farming operations to purchase the rights to underwater bay "land" (traditionally common property), and petered off in the 1920s, as silt and pollution disrupted the bay's ecosystem. At 15, Jack London bought a boat, the Razzle Dazzle, and joined the oyster pirates of San Francisco Bay to escape work as a child laborer. London wrote about his experiences in his semi-fictional autobiography, John Barleycorn, and used them in his early work, The Cruise of the Dazzler, and in his Tales of the Fish Patrol. The latter tells the story of oyster pirates from law enforcement's perspective—after sailing as an oyster pirate, London switched sides himself, to hunt his former compatriots.

At 15, Jack London bought a boat, the Razzle Dazzle, and joined the oyster pirates of San Francisco Bay to escape work as a child laborer. London wrote about his experiences in his semi-fictional autobiography, John Barleycorn, and used them in his early work, The Cruise of the Dazzler, and in his Tales of the Fish Patrol. The latter tells the story of oyster pirates from law enforcement's perspective—after sailing as an oyster pirate, London switched sides himself, to hunt his former compatriots. The working class romanticized oyster pirates as Robin-Hood-like heroes, fighting back against the new big businesses' private control of what had once been common land. Traditionally, underwater "real estate" was commonly owned—anyone with a boat or oyster tongs could fish or dredge without fear of trespassing. Following the Civil War, states began leasing maritime "land" out to private owners; and the public protested, by engaging in oyster piracy, supporting oyster pirates, scavenging in tidal flats and along the boundaries of maritime property, and, occasionally, engaging in armed uprisings.

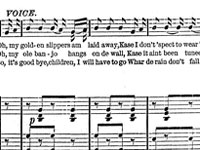

The working class romanticized oyster pirates as Robin-Hood-like heroes, fighting back against the new big businesses' private control of what had once been common land. Traditionally, underwater "real estate" was commonly owned—anyone with a boat or oyster tongs could fish or dredge without fear of trespassing. Following the Civil War, states began leasing maritime "land" out to private owners; and the public protested, by engaging in oyster piracy, supporting oyster pirates, scavenging in tidal flats and along the boundaries of maritime property, and, occasionally, engaging in armed uprisings.  The opera satirized Governor William Evelyn Cameron's second raid against oyster pirates in the Chesapeake Bay, on February 27, 1883. Cameron had conducted a very successful raid the previous February, capturing seven boats and 46 dredgers, later pardoning most of them to appease public opinion—which saw the pirates as remorseful, hard-working family men. His second raid, in 1883, went poorly. Almost all of the ships he and his crews chased escaped into Maryland waters, including the Dancing Molly, a sloop manned only by its captain's wife and two daughters (the men had been ashore when the governor started pursuit). The public hailed the pirates as heroes and ridiculed the governor in the popular media—the Lynchberg Advance, for instance, ran a

The opera satirized Governor William Evelyn Cameron's second raid against oyster pirates in the Chesapeake Bay, on February 27, 1883. Cameron had conducted a very successful raid the previous February, capturing seven boats and 46 dredgers, later pardoning most of them to appease public opinion—which saw the pirates as remorseful, hard-working family men. His second raid, in 1883, went poorly. Almost all of the ships he and his crews chased escaped into Maryland waters, including the Dancing Molly, a sloop manned only by its captain's wife and two daughters (the men had been ashore when the governor started pursuit). The public hailed the pirates as heroes and ridiculed the governor in the popular media—the Lynchberg Advance, for instance, ran a  Oyster piracy highlights the class tensions that sprang up during post-Civil War industrialization. Big business and private ownership began to drive the economy, shaping the lives of the working class and changing long-established institutions and daily patterns. Young people such as Jack London turned to oyster piracy as an escape from the new factory work—and the working class chaffed against the loss of traditional maritime common lands to business owners.

Oyster piracy highlights the class tensions that sprang up during post-Civil War industrialization. Big business and private ownership began to drive the economy, shaping the lives of the working class and changing long-established institutions and daily patterns. Young people such as Jack London turned to oyster piracy as an escape from the new factory work—and the working class chaffed against the loss of traditional maritime common lands to business owners.

Rubella

Rubella Diphtheria

Diphtheria  Smallpox

Smallpox  Polio

Polio The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website provides resources on (largely present-day) health and health practices, but its

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website provides resources on (largely present-day) health and health practices, but its

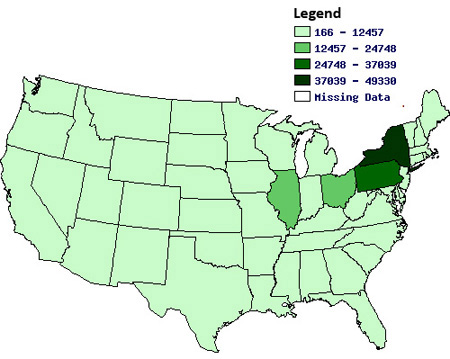

The map of the 1920 concentration of manufacturing establishments was generated by the University of Virginia Library's

The map of the 1920 concentration of manufacturing establishments was generated by the University of Virginia Library's

In 1790, federal marshals collected data for the first census, knocking by hand on each and every door. As directed by the U.S. Constitution, they counted the population based on specific criteria, including "males under 16 years, free White females, all other free persons (by sex and color), and slaves." There was no pre-printed form, however, so marshals submitted their returns, sometimes with additional information, in a variety of formats.

In 1790, federal marshals collected data for the first census, knocking by hand on each and every door. As directed by the U.S. Constitution, they counted the population based on specific criteria, including "males under 16 years, free White females, all other free persons (by sex and color), and slaves." There was no pre-printed form, however, so marshals submitted their returns, sometimes with additional information, in a variety of formats.

True. Or at least, he is recorded as doing so in colonist Robert Beverley's 1705 The History and Present State of Virginia, today a major resource in early Virginian and colonial history. Beverley gives a full account of Pocahontas's story (though historians debate its accuracy). According to Beverly, in England,

True. Or at least, he is recorded as doing so in colonist Robert Beverley's 1705 The History and Present State of Virginia, today a major resource in early Virginian and colonial history. Beverley gives a full account of Pocahontas's story (though historians debate its accuracy). According to Beverly, in England, False. Upon coming to the throne in 1891—following the death of her brother, King Kalakaua—Queen Lili'uokalani appointed Victoria Ka'iulani Cleghorn, her half-Scottish half-Hawaiian niece, as Crown Princess of Hawaii. Born in 1875 and educated in the UK, Ka'iulani spent the latter part of her short life advocating for the restoration of her country's independence. She died of illness in 1899, at the age of 23—shortly after the U.S. officially annexed Hawaii. The Hawaiian royal line continues today, but Ka'iulani was the last princess appointed while the monarchy held political power.

False. Upon coming to the throne in 1891—following the death of her brother, King Kalakaua—Queen Lili'uokalani appointed Victoria Ka'iulani Cleghorn, her half-Scottish half-Hawaiian niece, as Crown Princess of Hawaii. Born in 1875 and educated in the UK, Ka'iulani spent the latter part of her short life advocating for the restoration of her country's independence. She died of illness in 1899, at the age of 23—shortly after the U.S. officially annexed Hawaii. The Hawaiian royal line continues today, but Ka'iulani was the last princess appointed while the monarchy held political power.  False. The imperial family objected to the opening of Japan—which had kept its borders largely shut to outsiders for centuries—to the U.S., but the imperial princess' marriage did not take place until several years after the shogun concluded a second treaty, this one with the first U.S. Consul General to Japan, Townsend Harris. The shogunate, essentially a monarchy made up of warrior-rulers, had long held the power of government in Japan, while the traditional monarchy of the imperial family had become largely ceremonial. However, the shogunate's agreeing to open the country to Westerners in the treaties of 1854 and 1858 created a political divide between supporters of the shogun and of the emperor; Kazunomiya's marriage to Iemochi in 1862 was meant to bridge this divide.

False. The imperial family objected to the opening of Japan—which had kept its borders largely shut to outsiders for centuries—to the U.S., but the imperial princess' marriage did not take place until several years after the shogun concluded a second treaty, this one with the first U.S. Consul General to Japan, Townsend Harris. The shogunate, essentially a monarchy made up of warrior-rulers, had long held the power of government in Japan, while the traditional monarchy of the imperial family had become largely ceremonial. However, the shogunate's agreeing to open the country to Westerners in the treaties of 1854 and 1858 created a political divide between supporters of the shogun and of the emperor; Kazunomiya's marriage to Iemochi in 1862 was meant to bridge this divide. To read Robert Beverley's full account of the life of Pocahontas, refer to pages 25-33 of his The History and Present State of Virginia

To read Robert Beverley's full account of the life of Pocahontas, refer to pages 25-33 of his The History and Present State of Virginia

1915

1915 1925

1925 1917 (Note the military accents.)

1917 (Note the military accents.) 1905.

1905. 1935.

1935. 1910.

1910. 1940.

1940. 1895.

1895. 1955.

1955. 1960.

1960.

[Question 1] The first photograph of either a president or a first lady broadcasting from the White House is of Mrs. Hoover. She began national broadcasts in 1929, even setting up a practice room in the White House where she could "improve [her] talkie technique." Many of her broadcasts were made from President Hoover's country retreat, Camp Rapidan, where she often devoted her programs to speaking to young people, urging girls to contemplate independent careers and boys to help with the housework. Mrs. Hoover had a degree in geology from Stanford University, as did her husband. She had accompanied him to China for two years, where he hadsupervised the country's mining projects. She later used the Mandarin Chinese she learned then to communicate with her husband privately when they were in the presence of others.

[Question 1] The first photograph of either a president or a first lady broadcasting from the White House is of Mrs. Hoover. She began national broadcasts in 1929, even setting up a practice room in the White House where she could "improve [her] talkie technique." Many of her broadcasts were made from President Hoover's country retreat, Camp Rapidan, where she often devoted her programs to speaking to young people, urging girls to contemplate independent careers and boys to help with the housework. Mrs. Hoover had a degree in geology from Stanford University, as did her husband. She had accompanied him to China for two years, where he hadsupervised the country's mining projects. She later used the Mandarin Chinese she learned then to communicate with her husband privately when they were in the presence of others. [Question 4] Julia Grant, although it happened after her husband was no longer president. Mrs. Grant went down the Big Bonanza silver mine in Virginia City, Nevada with her husband after hearing that he had wagered that she would be afraid to go. The Grants, along with their son, Ulysses, Jr., visited the mine on October 28, 1879, more than two years after Grant had left office. The mine's fabulous production of silver during the Civil War had done much to undergird the Government's financial credit internationally. Lucy Hayes later descended into the same mine with her husband, President Rutherford Hayes. On May 21, 1935, Eleanor Roosevelt made the national news by visiting the Willow Grove coal mine in Bellaire, Ohio, to observe the working conditions of the miners.

[Question 4] Julia Grant, although it happened after her husband was no longer president. Mrs. Grant went down the Big Bonanza silver mine in Virginia City, Nevada with her husband after hearing that he had wagered that she would be afraid to go. The Grants, along with their son, Ulysses, Jr., visited the mine on October 28, 1879, more than two years after Grant had left office. The mine's fabulous production of silver during the Civil War had done much to undergird the Government's financial credit internationally. Lucy Hayes later descended into the same mine with her husband, President Rutherford Hayes. On May 21, 1935, Eleanor Roosevelt made the national news by visiting the Willow Grove coal mine in Bellaire, Ohio, to observe the working conditions of the miners. [Question 7] Lyndon Johnson, with his wife Lady Bird on one side and Jackie on the other, was sworn in aboard Air Force One less than two hours after JFK's assassination. The ceremony was delayed to wait for Jackie to arrive. The most famous photograph of the event has Jackie in the foreground, standing in a pink suit still stained with her husband's blood, with LBJ in the center with his hand upraised taking the oath, and with Lady Bird in the background.

[Question 7] Lyndon Johnson, with his wife Lady Bird on one side and Jackie on the other, was sworn in aboard Air Force One less than two hours after JFK's assassination. The ceremony was delayed to wait for Jackie to arrive. The most famous photograph of the event has Jackie in the foreground, standing in a pink suit still stained with her husband's blood, with LBJ in the center with his hand upraised taking the oath, and with Lady Bird in the background.