In 1900, the news reached the public all in print. The newspapers were at the height of their power and influence. They were inexpensive and ubiquitous throughout the country. It was their Golden Age, before newsreels, commercial radio, television, or the internet. The publishers and editors of the largest metropolitan daily newspapers of that time had enormous political and social influence. They became celebrities in their own right—including men such as Joseph Pulitzer, William Randolph Hearst, and Joseph Medill—who inherited the same notoriety that had attached itself in the preceding generation to Horace Greeley, James Gordon Bennett, and Charles Anderson Dana.

The Newspaper and Newsmagazine Business in 1900

George Rowell's American Newspaper Directory for 1900 and the Pettingill Advertising Agency's National Newspaper Directory and Gazetteer show that about 40 newspapers (at least in their Sunday editions) had a circulation of over 100,000, and that the largest newspapers were generally clustered in New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, and St. Louis. Competition for readers (and consequently for advertising revenue), especially among these largest newspapers, was fierce.

Competition for readers (and consequently for advertising revenue), especially among these largest newspapers, was fierce.

Rowell's Directory calculated that there were more than 20,000 different newspapers published in the United States (including dailies, weeklies, monthlies, and quarterlies) in 1900. Rowell's detailed listings show a large number of small newspapers serving even tiny hamlets and rural communities. They also show that a very large proportion of the regular papers clearly labeled themselves politically, either as Democrat, Republican, Independent, or Socialist. There were also many special interest newspapers—published in German or Yiddish or Swedish, for example, or published in quasi-magazine format, perhaps as infrequently as monthly, for such niche markets as women (fashion or homemaking); farmers; gardeners; Sunday School pupils; or members of particular occupations, fraternal or ethnic organizations, or religious denominations. Many of these mixed feature articles with news of the day. Typical of these were Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper and Harper's Magazine.

Cooperation and Competition

In 1900, newspapers shared news with one another. Papers across the country had long had the practice of exchanging copies of their papers by giving subscriptions to the editors of other papers upon request. Editors would scan through all the papers they received and would often clip articles and reprint them in their next editions (most often with attribution). Beginning with the formation of the Associated Press around 1850, newspapers began forming news-gathering cooperatives, whereby stories investigated by and reported in some of the largest newspapers, like The New York Herald and The Chicago Tribune, would be cabled to affiliated newspapers, which would run them simultaneously. By 1900 there were a handful of such cooperatives. Individual newspapers, depending on their financial resources, also had bureaus or single correspondents in cities around the country and abroad, and assigned reporters to travel to cover stories far afield.

Each edition typically operated on a 24-hour news cycle, which may not seem long, but it is leisurely compared to radio and TV news broadcasters.

Many cities were served by at least 2 competing daily newspapers—with the competitors each sympathetic to a different political party or published at the opposite end of the day. Each edition typically operated on a 24-hour news cycle, which may not seem long, but it is leisurely compared to the schedules of radio and TV news broadcasters, or reporters working on internet news sites today, who report and then update stories virtually from the time the news first breaks.

Yellow Journalism

Compared with broadcast journalism—or with the truncated editions of newspapers of today—the news cycle of 1900 often allowed reporters to develop their stories with more background and perspective. Compared to newspapers of the 1850s, however, readers in 1900 often complained of how reporters' and editors' reliance on the constantly chattering telegraph and telephone had seemingly turned the assembled news into a large unfermented mash, where the trivial and the important sat side by side. This had only increased by 1900, and was amplified by a literary fashion, which both affected and was affected by journalistic writing, toward realism and the reporting or muckraking of the corrupt, the sordid, and the everyday. As a result, the tone of the news—or, one might say, the objects that the newspapers felt called upon to report—had begun to change.

The trivial and the important sat side by side.

Joseph Pulitzer at The New York World and William Randolph Hearst at The New York Journal had begun to deploy teams of investigative reporters who tagged along on police calls and interviewed and reported the observations of bystanders and victims. They aggressively pumped witnesses at the scene and followed their own leads into back alleys and to criminal informants, very much in the style of detectives. This was a novel way of getting a news story. Many people felt that a line of propriety was being crossed, although it certainly made "good copy," in the sense that it sold well. Paradoxically, perhaps (because of the assumed moral judgment that motivates such muckraking), newspaper editors and publishers at the time made a point of disavowing any moral dimension to news writing and insisted that they were simply bringing to light things that were hidden.

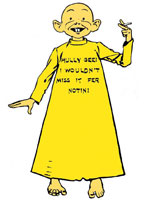

In 1900, the Spanish-American War had recently ended. It was around that conflict that Pulitzer and Hearst pushed an aggressive array of journalistic tactics to an extreme. The New York Press accused them of what it called "yellow journalism," informally linking their trafficking in exaggeration, rumors, lurid imagery, and sensationalism (as well as clandestine tactics to file stories that bypassed military censors on the telegraph lines) to the mischievous "Yellow Kid" comic character that ran in both papers.