While there are isolated instances of African Americans serving in the Confederate ranks, there is overwhelming evidence that this small number represents rare and exceptional cases: historian David Blight estimates that the number of black soldiers in the Confederate ranks was fewer than 200. That small number represents some partial companies of slaves training as soldiers discovered by Union forces after the fall of Richmond. One reason that only a handful of blacks fought for the Confederacy is that until the last weeks of the war, the Confederate Congress expressly forbade arming enslaved African Americans, who made up the vast majority of the black population in the South. Given white southerners' longstanding fears of a slave uprising (fears intensified by a few abortive attempts in the first half of the 19th century and exacerbated to the point of hysteria by John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry in 1859), the acute resistance of Confederates to arming blacks is understandable. Putting muskets in the hands of enslaved African Americans presented more than simply a concrete threat—embracing the notion that blacks could serve as soldiers in the same fashion as whites threatened deeply-held Southern ideas of race-based honor and masculinity. As Confederate Secretary of State Robert Toombs put it, "The day the army of Virginia allows a negro regiment to enter their lines as soldiers, they will be degraded, ruined, and disgraced."

Opposition to African American soldiers was passionate on both sides. The notion of fighting alongside blacks violated many deeply-held beliefs of white Northerners and Southerners alike.

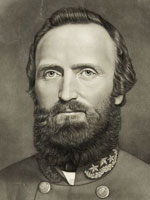

Northerners were scarcely more enthusiastic about arming African Americans than their Southern counterparts. For the first year and a half of the war, Abraham Lincoln's administration eschewed the enlistment of black troops, fearful of a public backlash. Not until Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, did the Union Army begin to enroll African Americans in its ranks; even then, the decision proved deeply controversial, particularly among Northern Democrats. The Confederacy did not seriously entertain the idea of arming enslaved African Americans until a full year later, when the war situation in the South had grown much more desperate. In January 1864, months after the defeats at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Patrick Cleburne (one of the most successful combat commanders in the Confederate Army) circulated a proposal to arm the slaves. Northern successes on the battlefield, Cleburne argued, threatened the South with "the loss of all we now hold most sacred—slaves and all other personal property, lands, homesteads, liberty, justice, safety, pride, manhood." Sacrificing the first, Cleburne held, could save the rest; the Confederacy could check Union advances by recruiting an army of slaves and guaranteeing freedom "within a reasonable time to every slave in the South who shall remain true to the Confederacy." A dozen of Cleburne's subordinates backed his proposal.

Lee wrote a letter to a Confederate congressman characterizing the plan as "not only expedient but necessary."

To most Southerners, however, Cleburne's plan was appalling. The prospect of arming the slaves struck one division commander as "revolting to Southern sentiment, Southern pride, and Southern honor." A brigade commander suggested that accepting enslaved African Americans as soldiers would "contravene the principles upon which we fight." Sensing the potential for the debate to cause dangerous dissension within the ranks, Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered the generals to cease the discussion. Debate over the decision to arm enslaved African Americans resurfaced many months later, as the Confederacy's situation grew progressively more dire both on and off the battlefield. When another similar proposal reemerged it carried the imprimatur of Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of Northern Virginia and perhaps the most revered figure in the South. In February 1865, Lee wrote a letter to a Confederate congressman characterizing the plan as "not only expedient but necessary." Even with Lee's support, though, the bill proved deeply divisive. It was not until March 13, 1865, just weeks before Lee's surrender, that the Confederate Congress passed legislation allowing for the enlistment of black soldiers. The two companies discovered by Union troops after the fall of Richmond never went into battle. Opposition to African American soldiers was passionate on both sides. The notion of fighting alongside blacks violated many deeply-held beliefs of white Northerners and Southerners alike. In the Union army, African Americans served in segregated regiments under white officers; many were used for menial tasks rather than fighting, and those that went into combat suffered abuse from their white comrades and were often singled out as targets by their Confederate foes. Nevertheless, the vast majority of African American troops fought bravely and with distinction, and by the end of the war, their actions in combat had begun to change the assumptions of at least some of their comrades regarding the fitness of blacks for battle. Despite their demonstrated fighting ability, it was nearly another full century before the United States Army finally desegregated individual units.