Stonewall Jackson and the Battle of Chancellorsville

Question

Why did Stonewall Jackson think that his army could fight all night long after the Battle of Chancellorsville?

Answer

Confederate General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson was one of the chief architects of the stunning Confederate victory at the battle of Chancellorsville, Virginia, on May 2, 1863. Along with overall Confederate commander Robert E. Lee, Jackson devised a daring plan that divided the numerically inferior southern army and then marched Jackson’s men far around the Union army to strike unsuspecting northern troops on their extreme right flank. Northern soldiers were caught almost completely unawares and quickly succumbed to panic and rout, resulting in one of the most striking tactical victories of the war. Jackson, eager to follow up the initial success by mounting an extremely rare nighttime attack, reconnoitered the Union lines by the light of a full moon the evening of the battle. It was his last act as commander.

Though the men of his corps were undoubtedly exhausted after the day’s fighting, there was reason to believe that they would summon the will for a follow-up attack. Jackson’s men had already proved themselves capable of feats of endurance far beyond what most Civil War-era units could accomplish. During their famed 1862 campaign in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, Jackson’s men marched over 400 miles during a four-week stretch (including one 57-mile march in 51 hours) and fought six battles that month, repeatedly confounding Union generals’ attempts to defeat them. That the troops in Jackson’s command managed these feats under extremely difficult conditions—many had poor equipment, insufficient rations, and suffered from dysentery and other chronic conditions—renders their achievements even more remarkable, and helps explain why Jackson’s infantry became known as his “foot cavalry.” Their record as some of the most battle-hardened troops in the Army of Northern Virginia may have led their commander to believe they could renew the attack even after a grueling day of battle. (Jackson also may have anticipated a relative advantage over his Union opponents, whose troops were not only exhausted from the day’s hard fighting but also suffering from low morale due to the chaos of their defeat earlier in the day.)

Night attacks like the one Jackson contemplated at Chancellorsville were extremely rare during the Civil War not because of fatigue but because of the difficulty of fighting in the dark. Even under the best of conditions, Civil War battles were chaotic and confusing affairs: absent modern communications technologies, regiments depended on brightly-colored flags and uniforms to distinguish friend from foe. Even in daylight, troops sometimes mistook friendly regiments for enemy units: the thick, heavy smoke produced by Civil War firearms hung close to the ground, obscuring lines, and in the first years of the war many units on both sides employed nonstandard uniforms. Nighttime amplified these problems, making it nearly impossible to determine the position of friendly and enemy units. The increased threat of so-called “friendly fire” casualties represented a powerful disincentive to mount nighttime operations.

Jackson himself became the best-known Civil War victim of friendly fire. While scouting the Union lines at Chancellorsville by moonlight on horseback with his aides, Confederate pickets mistook his party for northern troops and fired several volleys into the group. Jackson himself was struck by musket balls and mortally wounded: surgeons amputated his left arm in an attempt to save his life, but pneumonia set in and the famous general died eight days after the battle.

For more information

Maps of the Chancellorsville Campaign, in the American Civil War Atlas assembled by West Point.

Explanation of The Battle of Chancellorsville at the website of the Civil War Preservation Trust.

Bibliography

Images:

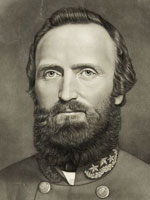

Print engraving of Stonewall Jackson. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

"Battle-field of Chancellorsville Trees shattered by artillery fire on south side of Plank Road near where Gen. Stonewall Jackson was shot," photograph, 1865. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.