The Standardization of American English

Why did American colonists spell so poorly?

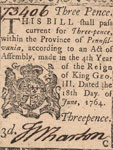

Although colonial Americans did not spell consistently, we should not assume that they were careless writers. The invention of the printing press and the Reformation’s encouragement of literacy helped to standardize spelling, but European nations and their colonies only slowly established consistent spelling rules. As late as the Revolution, the mix of cultures and languages and the small but growing number of presses slowed the progress of spelling standards in America.

Not all residents of Anglo-America used English as their first language. The British colonies contained French- and German-language schools, and many Americans read non-English newspapers and attended non-English religious services. In 1751, for example, Benjamin Franklin expressed concern about the proliferation of German-language newspapers, legal documents, and street signs in culturally diverse Pennsylvania. Even after the Revolution, a significant number of Americans continued to speak a native language other than English. In 1777 the Articles of Confederation were printed in French, and the Continental Congress printed some proceedings in German. According to the 1790 census, about 20% of the new nation’s population spoke a language other than English as their first language. Because of the assortment of languages in the new nation, residents placed little emphasis on standardization of spelling.

In the early republic, however, language became an important consideration in creating a culturally distinctive nation. As they tried to create their own identity, a few Americans began to distinguish American language from English through changes in spelling and punctuation. One of the biggest proponents of language reform was Noah Webster, a New England lawyer and scholar. Webster argued that even the smallest regional differences in spelling and pronunciation could turn into political difference, resulting in dangerous factions. He traveled around the U.S. giving lectures about standardizing the English language, and in his travels he met Benjamin Franklin, who shared Webster’s concerns about language reform. Franklin proposed deleting the letters c, w, y, and j and adding six new letters to the American alphabet. Webster, however, did not like the idea of adding or subtracting letters, but rather he wanted to simplify the spelling of words—changing favour to favor, for example, or replacing the -re with -er in centre/center and theatre/theater, in order to match spelling with pronunciation. Webster’s speller, which he first published in 1783, and his American Dictionary of the English Language (1828) helped to facilitate homogenization. Also in this time period, printers began to standardize spelling in order to make the printing process more efficient.

Not all of Webster’s standardization ideas took. For example, words such as “through,” “bureau,” and “laugh” are still not spelled as they sound. Moreover, American reformers instituted spelling standards gradually. Manuscripts from the 19th and 20th centuries still reveal irregular spelling, although we can attribute much of that to inconsistent access to education and uneven educational standards. Luckily these days we have spell check!

Dillard, J.L. A History of American English. New York: Longman Publishing, 1992.

Simpson, David. The Politics of American English, 1776-1850. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Websites of Interest:

Film Study Center, Harvard University, “How to Read 18th Century British-American Writing.” DoHistory.org. Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media.

Noah Webster biography at the Noah Webster House website.

Baron, Dennis E. Grammar and Good Taste: Reforming the American Language. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1982.

Lepore, Jill. A Is For American: Letters and Other Characters in the Newly United States. New York: Vintage Books, 2003.

Webster, Noah. The Autobiographies of Noah Webster. Edited by Richard M. Rollins. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1989.