What is it?

Crop It is a four-step hands-on learning routine where teachers pose questions and students use paper cropping tools to deeply explore a visual primary source.

Rationale

In our fast-paced daily activities we make sense of thousands of images in just a short glance. Crop It slows the sense-making process down to provide time for students to think. It gives them a way to seek evidence, multiple viewpoints, and a deeper, more detailed, understanding before determining the meaning of a primary source.

Description

This routine helps young students look carefully at a primary source to focus on details and visual information and use these to generate and support ideas. Students use evidence from their “crops” to build an interpretation or make a claim. Crop It can be completed as part of a lesson, and can be used with different kinds of visual sources (for example cropping a work of art, a poem, or a page from a textbook).

Teacher Preparation

- Print a collection of primary sources related to the unit or topic under study. The collection may include:

-

- various types of sources that include images, such as photographs, cartoons, advertisements, and newspaper articles. Consider images that challenge students to use varying amounts of background knowledge and vocabulary, or that can be read by students working on different reading levels;

- sources representing different perspectives on the topic;

- sources depicting the people, places, and events that will be tested in a unit;

- sources representing perspectives that are missing from the textbook’s account.

- Print enough copies so each student can have one source: it’s fine if some students have the same image.

- Print and cut out enough Crop It tools so that each student has a set of two tools.

- Prepare to display a series of questions either through a PowerPoint presentation or on chart paper.

In the Classroom

Step One: Choose an Image

Ask students to choose a source from the collection that either:

-

- connects to an experience that you have had;

- relates to something that you know a lot about, and/or

- leaves you with questions.

*Note: other criteria may be substituted such as choose an image that relates to a question you have about the unit, relates to your favorite part of this unit, or that represents the most important topic or idea of this unit.

Step Two: Explore the Image

Crop the image to the part that first caught your eye. Think: Why did you notice this part? Crop to show who or what this image is about. Think: Why is this person or thing important? Crop to a clue that shows where this takes place. Think: What has happened at this place?

- Pass out a set of two Crop It tools to each student. Demonstrate how to use the Crop It tools to focus on a particular piece of a source. Students can make various sizes of triangles, rectangles, and lines to “crop” or focus attention on an important part of the source.

- Invite students to carefully explore their image by using the tools. Pose a question and ask students to look carefully and “crop” to an answer. For example, ask students to:

- (See Question Sets Handout for additional sample questions.) Invite students to revise their answer by choosing another crop that could answer the same question. Encourage students to consider: if they could only have one answer, then which crop would be best? Why? Allow students to look at the crops of other students. Students can explain their crop to a partner. Or ask students to place their source and crop on their desk, and invite students to silently walk around and notice the different types of evidence that students used to answer the same question.

Step Three: Identify the Evidence

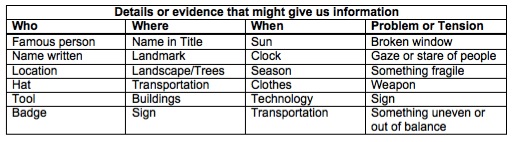

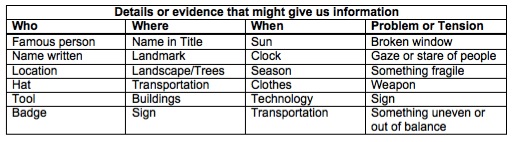

Collect the types of evidence students cropped on large chart paper by asking them to recall the different types of details that they cropped. These charts encourage students to notice details and can be used later, when adding descriptions to writing or as supports for answers during class discussions. The charts might look like the example below and will constantly grow as students discover how details help them build meaning.

Step Four: Close the Lesson

Conclude the lesson by asking students what they learned about the topic related to the collection. Ask them to reflect on what they learned about looking at sources, and when in their life they might use the Crop It routine to understand something.

Common Pitfalls

Avoid asking too many questions during Step Two: Explore. Keep the questions and the cropping moving fairly quickly so students stay engaged and focused on their primary source. To increase the amount of thinking for everyone, don’t allow students to share their own crops with a partner or the class right away. Ask students to revise their own crop by trying different ideas before sharing.

Example

See Image Set Handout for samples that you might use with this strategy. These images represent some events key to understanding the Great Depression of the 1930s (e.g., FDR’s inauguration and the Bonus Army’s march on Washington) and could be used to review or preview a unit of study.