What Is It?

KWL Guides—what do I know, what do I want to know, what have I learned—offer a straightforward way to engage students in historical investigation and source analysis.

Rationale

Using KWL guides in elementary history classes empowers students and teachers.

- KWL guides engage students via a simple format. They place the students' observations, questions, and knowledge development at the center of exploring historical sources. Students are able to connect new knowledge to prior knowledge, and generate and investigate questions.

- Most elementary teachers are familiar with KWL guides to structure inquiry in various subjects, from literature to science, but analyzing primary historical sources can be a new experience, leaving teachers hesitant to incorporate them in their teaching. Applying the KWL approach to primary source analysis encourages teachers to adopt a constructivist approach to history instruction, as it taps their confidence in using a familiar strategy to teach a new subject.

Description

The KWL chart is a metacognition strategy designed by Donna Ogle in 1986. It prompts students to activate prior knowledge, generate questions to investigate, and inventory the new knowledge that emerges from investigation. The acronym stands for: K: students identify what they already KNOW about a subject. W: students generate questions about what they WANT to learn about the subject. L: students identify what they LEARNED as they investigated. In lower elementary history studies, the entire class looks at projected images or documents and together fills out a KWL chart. In the middle grades teachers may model the process. Once students gain proficiency, they are allowed to work in pairs or groups. Primary sources can be incorporated at various times during a history lesson. Teachers may use them to introduce a unit or to expand a student's understanding and empathy for a topic. Directions below describe how to use the KWL primary source analysis during a unit, but they are easily adapted to use at the start of a unit.

Teacher Preparation

- Choose a source to explore with your students. Books in school or public libraries also offer historical images and documents.

Source Subject When seeking images, artifacts, or written documents that align with your history unit, consider four ways that primary sources enhance history learning:

- Motivate historical inquiry

- Supply evidence for historical accounts

- Convey information about the past

- Provide insight into the thoughts and experiences of people in the past ()

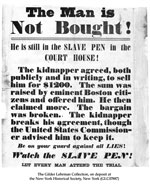

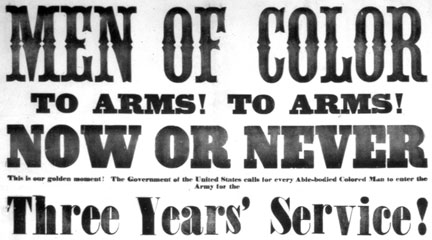

Your source should match one or more of these criteria; they are not mutually exclusive. You may find a source that you believe will motivate your students' learning and it also provides a vivid, intriguing glimpse into the experiences of people in the past. Or you may choose to examine with your class a source cited as evidence in one of the historical accounts that you read together, and then discover the source conveys additional information about your topic. Source Format In terms of primary sources, elementary schoolchildren often engage most successfully with visual images, especially pictures that feature children or dramatic action. Don't discount written documents, however, especially in the middle grades, although you might need to abridge a lengthy document or model the process of paraphrasing with short excerpts.

- Copy the source to an overhead transparency or into a file for an LCD projector. You can give students their own copies to view at their desks and put in their history folders, and post one on the class's history timeline.

- Decide when you will examine the source. To scaffold source explorations, schedule them between reading historical fiction and/or nonfiction to provide context.

- Decide how to display and write on the class KWL chart. Using a transparency is fine, but could limit ongoing student access to the chart. ]KWL charts can be constructed on poster boards, whiteboards, or butcher paper for permanent display; these can be added onto as you explore other elements of your history unit. The posted chart is a visual reminder of students' growing prior knowledge as they move on to investigate other sources. When they are asked to interpret new sources, they can reference what they have studied previously. For students working in groups, make copies of the KWL chart for all students.

In the Classroom

1. Review the class's history learning to this point. Have students take turns walking and talking sections of your unit timeline, or ask students to brainstorm important themes they have explored thus far. In middle elementary, ask students to pair up and explain to another student what they learned the previous day. For lower elementary, call on students at random to share their thoughts with the whole class. 2. Following this review, explain that students can explore more about (the unit topic) by studying an information source from the actual time of the historic event. To illustrate this idea, contrast the date of the source you are examining with the copyright date of a fiction or nonfiction book you have read to your class. Eventually, at the end of this activity, you will return to the book and help your students understand how its author may have examined primary sources as s/he prepared to write it. 3. Introduce the KWL chart with knowledge questions as a guide to explore a source. If you have not used a KWL before, or if students are not familiar with the format, explain what the letters stand for and how they help us look closely at a source of information, make a list of what we already know about the source, and ask questions to help us learn more. 4. Model the KWL process with the entire class. Project a source via LCD or overhead projector. Conduct the K portion of your KWL (what do I think I already know about this source). After students carefully read or view the source, brainstorm a list of things they know about the image, artifact, or document. To help students activate their knowledge, structure interactions with sources by asking:

What/who do you think is in the source? (inventory the objects in an image or the components of a written source) What do you think is happening? (summarize the action or meaning) When do you think it is happening? Why do you think it is happening? Why do you think someone created the source in the first place? How did you come up with your answers? If people appear in the document or image, how do you think they felt?

5. Conduct the W portion (what do I want to know and how can I find out more). Ask students to:

Brainstorm aspects of the source they are uncertain about Brainstorm a list of questions about the source itself Brainstorm how they might find answers to their questions

6. Conduct the L portion of your KWL (what I've learned about or from this source).

Seek answers to the questions, or return to them as you investigate other sources and topics for your history unit and as answers emerge from those explorations. If you decide to investigate some questions right away, have the entire class work together, or divide students into groups and assign each group a question to investigate. Groups can use such research resources as the internet, school media center, or oral history interviews. Give the groups any books related to their question. When you send groups to the media center/library, alert your media specialist in advance so s/he may assist students with their searches. This activity is an excellent way to introduce or reinforce the use of search engines, tables of contents, and indexes to locate information. Update the guide by inventorying what your students have learned about the source and about the larger history topic by studying this source.

7. Brainstorm and take inventory of remaining unanswered questions raised by students while investigating the source.

Common Pitfalls

Extend learning for better readers. Ask them to decipher and summarize the document. They can then share their results with the rest of the class. If you determine a document is too difficult for any of your readers to decipher, create a simpler version for students to study.

- Copying images. Sometimes it's difficult to get a good copy. File size and type vary and may affect the quality of a reproduced image. If you find an image you want to use but it does not copy clearly, try using Google or another internet image search engine to locate that image in a different format or size.

- Selecting documents. When a document is only available in an original handwritten form, deciphering it can pose a challenge for teachers as well as students. Try to find documents that have been transcribed into readable type.

- Some documents are beyond the comprehension level of those students who read at or below grade level. If you want to use a source that fits this scenario, try the following:

- A common pitfall in executing KWL is the inclination to close discussion following the L step. Authentic learning exploration begins and ends with questions. When teachers demonstrate that it's natural and desirable to have ongoing questions, they send the message that questions are a crucial part of education. Asking questions doesn't indicate a lack of knowledge, but is evidence of an active mind. To honor questioning as the foundation of learning, KWL should perhaps add a fourth step: Q.

Example

KWL Image Exploration: Segregated Public Places The history of Jim Crow laws in the U.S. is the history of segregated neighborhoods, schools, public areas, hotels, restaurants, marriage, transportation—essentially every aspect of daily life. Though these practices were outlawed by civil rights legislation in the 1960s, their legacy of poverty and prejudice persists. It is essential that today's students not only learn the history of segregation but care about its aftereffects. Photos of Whites Only and Colored signs on water fountains, restrooms, waiting rooms, and entrances to buildings are powerful resources that engage student empathy for the African American experience under Jim Crow. This KWL photo analysis is most effective when preceded by explorations of pre-slavery African cultures, slavery, the Civil War, the 13th and 15th Constitutional Amendments, and sharecropping. As the first activity that explores segregation laws, it illustrates the reality of separate public accommodation as humiliating, degrading, and a clear signal that not all people were considered equal in America.

Acknowledgments

Credit for first using KWL as a historical source analysis guide goes to the second- and third-grade teachers who piloted the Bringing History Home curriculum at the Washington Community School District in Washington, Iowa. These teachers came up with KWL as a simple alternative to the NARA historical analysis guides. I am, as always, deeply indebted to BHH teachers for their innovative, inspired ideas.

These four effective uses of primary sources are identified by Keith Barton in Barton, K. "Primary Sources in History: Breaking Through the Myths," Phi Delta Kappan Vol. 86 Issue 10 (2005): 745-753.