Joe Jelen: Old Newspapers Find a Home in New Technology

Increasingly, people are turning to online outlets for their daily news (see Pew Research Center’s State of the Media Report). In fact, when I watch students interact with newspapers, they almost seem to treat newspapers as quaint. The reality is that newspapers remain great records of history, and today’s newspapers continue to reflect society's concerns and values. Social studies teachers should continue to teach students how newspapers are laid out and how effective news stories are written.

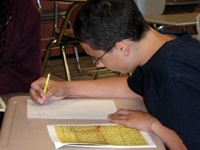

Consider putting an old newspaper in the hands of students. It does not need to be a special newspaper to hold significant information for students to analyze. While it would be neat for students to hold the front page of the Washington Post from the day Neil Armstrong stepped foot on the moon or Pearl Harbor was attacked, “atmosphere” newspapers can be just as illuminating and cheaper to obtain. An “atmosphere” newspaper can come from the era of World War I, World War II, or the space race, but not have a specific notable headline. These newspapers can be bought online from sites like eBay or online dealers for less than five dollars, more for older newspapers.

If laying hands on an actual old newspaper seems unnecessary, there are plenty of sites that will help you find articles related to your desired era of study. Chronicling America is part of the Library of Congress’s collection and contains searchable newspaper pages from 1860 to 1922. The Google News Archive contains a searchable database of many newspapers, largely from the 20th and 21st centuries. Finally, this site contains a great collection of Civil War-era copies of Harper’s Weekly.

In addition, many newspapers like the New York Times maintain a searchable archive of old articles, some viewable for free and others for a fee. However, many of these same types of big newspaper archives can be searched using subscription services from your school library.

While there are lots of ways to use your local newspaper in the classroom, there are a few sites that stand out for bringing newspapers from around the world to your computer.

Newspapermap.com displays a clickable map of available online newspapers from around the world. The site also offers to translate foreign newspapers. I've found that students get a sense of population distribution in the world and language distribution using this map.

The Newseum has a cool map that displays the day’s front pages from around the world. This can provide students an opportunity to see what makes news in different parts of the world and different parts of the United States.

In a history classroom, students could compare a newspaper today with a newspaper from 25, 50, or 100 years ago. This comparison can be a jumping-off point to several important conversations with students, perhaps even ending with predictions of what news will look like 25 years from now. Likely when students compare newspapers of today with newspapers of the past they will find that there was more paper dedicated to a newspaper (paper costs have increased over time, condensing newspaper size). Students will also find more wire stories, more local news, and more color printing in the newspapers of today.

Another lesson idea to help students practice summarizing main ideas is to cover up the headlines of a few articles and have students develop their own. Students can share their headlines aloud or post headlines anonymously on a wall to gauge understanding as a whole class.

To better understand the past, perhaps students could categorize articles from an old newspaper. Students could categorize according to bias vs. unbiased articles (or categorize by different types of bias), or articles dealing with the federal government vs. state government. This largely depends on the lesson objective.

Finally, students could rewrite newspaper articles with new information or using additional eyewitness accounts. By rewriting articles students are forced to detect bias or corroborate additional sources with their assigned newspaper article. For effect, students can create their own newspaper clippings using this site.

Newspapers offer students a unique glimpse into the past and, alongside new technology, offer fun ways to better understand past, present, and future.

Historian John Buescher has more suggestions for finding archived newspaper articles online, and our Website Reviews can guide you to even more options. Professor John Lee reminds readers that students (and teachers) may have scrapbooked newspaper articles in their homes, as well.

And don't feel limited to the articles! A close reading of a newspaper illustration, photograph, or cartoon can reveal just as much, as 4th-grade teacher Stacy Hoeflich demonstrates.