Today's textbooks represent a system of learning and knowledge transfer that is centuries old and sorely outpaced by modern technologies. Digital textbook providers are changing the textbook paradigm but, of course, adoption is the key. Do we dare take a new direction with the authorship and delivery of educational resources? We cannot afford not to.

Traditional textbooks are often expensive, rigid, and difficult to update. It is not unusual for these texts to be out of date before they go to the book binder, leaving many students learning from outdated materials that cannot be customized, individualized, or leveraged for multimedia.

Take, for example, an article in the San Francisco Chronicle on June 29, 2011, reporting that at a local school four blue recycle bins were found filled with hundreds of unused workbooks that ranged in price from $10 retail to about $24 each. The books were supplemental English and math workbooks that came in a set with textbooks supplied by publishers. The school principal explained that districts or schools typically sign multi-year contracts with textbook publishers, which provide one set of textbooks and supplemental workbooks for every student each year. Sometimes, teachers choose not to use the student workbooks. In other cases, schools might switch midstream to a newer textbook that more closely aligns to the questions on state standardized tests, and the result is that many of the workbooks go unused.

How can we, in good conscience, accept this waste when school districts are faced with ever-tightening budgets? How much longer can we let our students suffer the consequences of outdated resources?

This is just one example of how schools deal with outdated learning materials but I assure you similar examples exist throughout the country. How can we, in good conscience, accept this waste when school districts are faced with ever-tightening budgets? How much longer can we let our students suffer the consequences of outdated resources?

CK-12 was founded in 2007 with the mission of reducing textbook costs worldwide. The fact that schools across the world are facing these textbook dilemmas fuels the CK-12 team's commitment to eradicate such waste and to provide high-quality, standards-aligned open-source FlexBooks.

Why Digital?

Quality, of course, is a critical part of the textbook equation. Unlike the rigidity of traditional textbooks, the flexibility of digital textbooks allows teachers to easily update content for accuracy and relevancy. For example, a U.S. history teacher using digital learning resources can easily update content related to September 11th with information covering the 2011 capture of Osama Bin Laden.

Perhaps the most compelling argument for digital textbooks is that they allow teachers to create scaffolded learning tools for students. We know that one text does not fit all. With digital textbooks, the materials can be adapted as needed by teachers to enhance the learning experience for students.

Unlike the rigidity of traditional textbooks, the flexibility of digital textbooks allows teachers to easily update content for accuracy and relevancy.

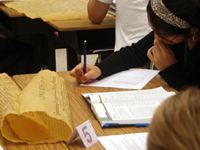

CK-12 and Leadership Public Schools [LPS], a network of four urban charter schools in the Bay Area, have forged a compelling digital textbook partnership that is making a measurable difference for students in need. Together, we created customized College Access Readers featuring embedded literacy supports to help bridge the achievement gap for an urban student population whose majority enter 9th grade reading between 2nd- and 6th-grade levels with math skills at the same levels.

LPS is using Algebra College Access Readers and FlexMath, an online Algebra support and numeracy remediation approach developed by LPS in partnership with CK-12 Foundation. LPS Richmond has also integrated immediate-response data with clickers.

Recent semester exams showed 92% at or above grade level, triple their performance last year and four times that of neighboring schools. This progress is particularly notable in a school in one of the highest poverty communities in California, Richmond's Iron Triangle.

So yes, the time for digital textbooks is here. The supply of quality digital textbooks is growing, as is the evidence of their positive impact. Now school administrators need to ensure their schools have the technology infrastructure and the appropriate teacher training in place to achieve widespread digital textbook adoption. Our teachers and students cannot afford for us to wait any longer.