American Personalities: Uncle Sam and Lady Liberty

Uncle Sam and Lady Liberty—for over a century, these two characters have personified the United States and popular conception of the nation’s ideals. Answer these questions about the roles these characters have played, including soldier, tyrant, police officer, financier, judge, deity, and champion of the oppressed.

1. What characters have political cartoonists used to represent the English counterparts to Uncle Sam and Lady Liberty?

c. John Bull and Britannia.

Wearing breeches and a Union Jack waistcoat, John Bull once served as the symbol for the British everyman, but evolved into a symbol of the country as a whole. Both Britannia, the goddess-like female figure of England, and John Bull often appeared in political cartoons with Uncle Sam or Columbia—another name for Lady Liberty.

Wearing breeches and a Union Jack waistcoat, John Bull once served as the symbol for the British everyman, but evolved into a symbol of the country as a whole. Both Britannia, the goddess-like female figure of England, and John Bull often appeared in political cartoons with Uncle Sam or Columbia—another name for Lady Liberty.

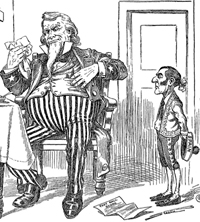

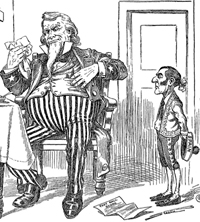

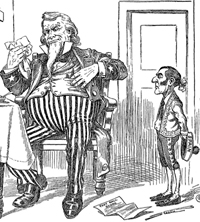

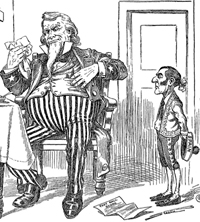

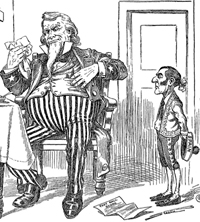

2. This version of Uncle Sam appeared in a Denver Evening Post cartoon in November 1898. Uncle Sam is usually drawn as a skinny character. Why is he fat here?

b. He has just finished consuming overseas territories, such as Hawaii, Puerto Rico and the Philippines.

In a spree of imperialism, the United States, represented by Uncle Sam, has "consumed" Hawaii (annexed to the U.S. on July, 1898), as well as Puerto Rico and the Philippines (though the Treaty of Paris and the acquisition of these as territories was still in debate in November 1898). Now, Uncle Sam turns to the figure of Spain—the cartoon's caption has him say, "Now, young man, I'll attend to your case." With the Spanish-American War over, the glutted U.S. prepares to attend to Spain itself, not just its colonies.

In a spree of imperialism, the United States, represented by Uncle Sam, has "consumed" Hawaii (annexed to the U.S. on July, 1898), as well as Puerto Rico and the Philippines (though the Treaty of Paris and the acquisition of these as territories was still in debate in November 1898). Now, Uncle Sam turns to the figure of Spain—the cartoon's caption has him say, "Now, young man, I'll attend to your case." With the Spanish-American War over, the glutted U.S. prepares to attend to Spain itself, not just its colonies.

3. When did political cartoonists draw Uncle Sam as a self-appointed global policeman?

d. During the "Imperialist" phase of U.S. foreign affairs, beginning prior to the Spanish-American War.

In the years leading up to the Spanish-American War and the U.S. metamorphosis into an imperialist world power, Uncle Sam was often drawn as a police officer. However, cartoonist Thomas Nast had already pictured Uncle Sam as a cop on the beat, policing U.S. political corruption, as early as 1888.

In the years leading up to the Spanish-American War and the U.S. metamorphosis into an imperialist world power, Uncle Sam was often drawn as a police officer. However, cartoonist Thomas Nast had already pictured Uncle Sam as a cop on the beat, policing U.S. political corruption, as early as 1888.

4. When Uncle Sam first appeared, he was drawn to resemble:

a. An old gentleman in knee breeches.

For several decades, Uncle Sam was indistinguishable from an earlier character, Brother Jonathan, who also represented the U.S., superceding Yankee Doodle. By the middle of the 19th century, the same figure-by then clad in striped pants, short jacket, and top hat—was sometimes called Uncle Sam and sometimes Brother Jonathan. By about 1875, "Brother Jonathan" had mostly disappeared.

For several decades, Uncle Sam was indistinguishable from an earlier character, Brother Jonathan, who also represented the U.S., superceding Yankee Doodle. By the middle of the 19th century, the same figure-by then clad in striped pants, short jacket, and top hat—was sometimes called Uncle Sam and sometimes Brother Jonathan. By about 1875, "Brother Jonathan" had mostly disappeared.

5. When Columbia first appeared, she most closely resembled:

a. The goddess of liberty, Libertas.

Often depicted in the French Revolution, Libertas wore a soft "liberty" or "Phrygian" cap. As Columbia, she could also wear feathers on her head, a reference to Native Americans, or a star or crown. The name "Columbia" fell out of popularity after World War I, and the character gained the names "Miss Liberty" or "Lady Liberty."

Often depicted in the French Revolution, Libertas wore a soft "liberty" or "Phrygian" cap. As Columbia, she could also wear feathers on her head, a reference to Native Americans, or a star or crown. The name "Columbia" fell out of popularity after World War I, and the character gained the names "Miss Liberty" or "Lady Liberty."

The Library of Congress, as part of its American Treasures exhibit, looks at the history of the famous "I Want You" World War I image of Uncle Sam. It also showcases an image, by the same artist, of Lady Liberty.

Uncle Sam and Lady Liberty have appeared regularly in political cartoons since their creation. Vassar College's 1896: The Presidential Campaign includes a subsection just for cartoons containing Uncle Sam, as does Leo Robert Klein's The Red Scare (1918-1921) (see "Uncle Sam" under subject headings). Even Dr. Seuss took his turn drawing Uncle Sam: Try June 1942 in Dr. Seuss Went to War: A Catalog of Political Cartoons. You might also try a search for the term "uncle sam" in the New York Public Library's Digital Archive.

Once you've found some resources picturing these iconic personifications, take a look at Understanding and Interpreting Political Cartoons in the History Classroom for models of classroom use.

- "Have Your Answers Ready," 1917, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Collection (accessed November 12, 2009).

- James Baillie, "Uncle Sam and his servants" (New York: 1844), Prints and Photographs Collection, Library of Congress (accessed November 12, 2009).

visible each November, blazed with extraordinary strength. The falling stars caught the attention of people throughout North America, and many Lakota bands chose the shower as the event to stand for the year. Later in the 1800s, ethnologist Garrick Mallery (1831-1894) identified the pictures as standing for the meteor shower, allowing scholars to match the years of the winter counts with the European calendar.

visible each November, blazed with extraordinary strength. The falling stars caught the attention of people throughout North America, and many Lakota bands chose the shower as the event to stand for the year. Later in the 1800s, ethnologist Garrick Mallery (1831-1894) identified the pictures as standing for the meteor shower, allowing scholars to match the years of the winter counts with the European calendar. introduced peg calendars to the Native peoples of Alaska so that they could track the holy days of the Russian Orthodox Church. Russian contact with Alaskan cultures began in the 1700s, and settlement of the region, accompanied by cultural exchange, continued until 1867, when the U.S. purchased Alaska from the Russians. Peg calendars remained in use into the 20th century.

introduced peg calendars to the Native peoples of Alaska so that they could track the holy days of the Russian Orthodox Church. Russian contact with Alaskan cultures began in the 1700s, and settlement of the region, accompanied by cultural exchange, continued until 1867, when the U.S. purchased Alaska from the Russians. Peg calendars remained in use into the 20th century. to record the passing of time in this manner. However, the use of calendar sticks was not limited to the Winnebago. Other Native American groups throughout North America used sticks, including the Pima, the Osage, and the Zuni. The markings on sticks and their daily and ceremonial use varied from region to region and people to people.

to record the passing of time in this manner. However, the use of calendar sticks was not limited to the Winnebago. Other Native American groups throughout North America used sticks, including the Pima, the Osage, and the Zuni. The markings on sticks and their daily and ceremonial use varied from region to region and people to people. one beginning around the summer solstice (June 20th or 21st) and the other with the winter solstice (December 21st or 22nd). After the winter solstice, katsinam, benevolent spirits, visit the Hopi people, personated by Hopi men in masks and costumes. Following the summer solstice, the katsinam leave the Hopi again.

one beginning around the summer solstice (June 20th or 21st) and the other with the winter solstice (December 21st or 22nd). After the winter solstice, katsinam, benevolent spirits, visit the Hopi people, personated by Hopi men in masks and costumes. Following the summer solstice, the katsinam leave the Hopi again. The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History's online exhibit

The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History's online exhibit

In 1790, federal marshals collected data for the first census, knocking by hand on each and every door. As directed by the U.S. Constitution, they counted the population based on specific criteria, including "males under 16 years, free White females, all other free persons (by sex and color), and slaves." There was no pre-printed form, however, so marshals submitted their returns, sometimes with additional information, in a variety of formats.

In 1790, federal marshals collected data for the first census, knocking by hand on each and every door. As directed by the U.S. Constitution, they counted the population based on specific criteria, including "males under 16 years, free White females, all other free persons (by sex and color), and slaves." There was no pre-printed form, however, so marshals submitted their returns, sometimes with additional information, in a variety of formats.

[Question 1] The first photograph of either a president or a first lady broadcasting from the White House is of Mrs. Hoover. She began national broadcasts in 1929, even setting up a practice room in the White House where she could "improve [her] talkie technique." Many of her broadcasts were made from President Hoover's country retreat, Camp Rapidan, where she often devoted her programs to speaking to young people, urging girls to contemplate independent careers and boys to help with the housework. Mrs. Hoover had a degree in geology from Stanford University, as did her husband. She had accompanied him to China for two years, where he hadsupervised the country's mining projects. She later used the Mandarin Chinese she learned then to communicate with her husband privately when they were in the presence of others.

[Question 1] The first photograph of either a president or a first lady broadcasting from the White House is of Mrs. Hoover. She began national broadcasts in 1929, even setting up a practice room in the White House where she could "improve [her] talkie technique." Many of her broadcasts were made from President Hoover's country retreat, Camp Rapidan, where she often devoted her programs to speaking to young people, urging girls to contemplate independent careers and boys to help with the housework. Mrs. Hoover had a degree in geology from Stanford University, as did her husband. She had accompanied him to China for two years, where he hadsupervised the country's mining projects. She later used the Mandarin Chinese she learned then to communicate with her husband privately when they were in the presence of others. [Question 4] Julia Grant, although it happened after her husband was no longer president. Mrs. Grant went down the Big Bonanza silver mine in Virginia City, Nevada with her husband after hearing that he had wagered that she would be afraid to go. The Grants, along with their son, Ulysses, Jr., visited the mine on October 28, 1879, more than two years after Grant had left office. The mine's fabulous production of silver during the Civil War had done much to undergird the Government's financial credit internationally. Lucy Hayes later descended into the same mine with her husband, President Rutherford Hayes. On May 21, 1935, Eleanor Roosevelt made the national news by visiting the Willow Grove coal mine in Bellaire, Ohio, to observe the working conditions of the miners.

[Question 4] Julia Grant, although it happened after her husband was no longer president. Mrs. Grant went down the Big Bonanza silver mine in Virginia City, Nevada with her husband after hearing that he had wagered that she would be afraid to go. The Grants, along with their son, Ulysses, Jr., visited the mine on October 28, 1879, more than two years after Grant had left office. The mine's fabulous production of silver during the Civil War had done much to undergird the Government's financial credit internationally. Lucy Hayes later descended into the same mine with her husband, President Rutherford Hayes. On May 21, 1935, Eleanor Roosevelt made the national news by visiting the Willow Grove coal mine in Bellaire, Ohio, to observe the working conditions of the miners. [Question 7] Lyndon Johnson, with his wife Lady Bird on one side and Jackie on the other, was sworn in aboard Air Force One less than two hours after JFK's assassination. The ceremony was delayed to wait for Jackie to arrive. The most famous photograph of the event has Jackie in the foreground, standing in a pink suit still stained with her husband's blood, with LBJ in the center with his hand upraised taking the oath, and with Lady Bird in the background.

[Question 7] Lyndon Johnson, with his wife Lady Bird on one side and Jackie on the other, was sworn in aboard Air Force One less than two hours after JFK's assassination. The ceremony was delayed to wait for Jackie to arrive. The most famous photograph of the event has Jackie in the foreground, standing in a pink suit still stained with her husband's blood, with LBJ in the center with his hand upraised taking the oath, and with Lady Bird in the background.

When the phonograph's huge potential in the mass distribution of music to the public became clear to Edison, he had his company begin recording and selling cylinders of musical performances. These cylinders, at the beginning, were not made with the intention to be sold to the public, but rather to be played on commercial phonographic machines, like jukeboxes. Even after he began pursuing a mass market for prerecorded music, however, his vision of the true potential of the phonograph seems to have faltered: he oversaw his company's selection of performers, and his library of musical choices was notoriously conservative and uninspired, and he later resisted using the technical innovation of electric recording via a microphone, continuing to use the process of acoustic recording, which required performers to play and sing into a wooden horn that mechanically focused the sound onto the needle that cut the groove in the master cylinder. He also resisted switching from cylinders to discs until 1913, well after other manufacturers had made the switch.

When the phonograph's huge potential in the mass distribution of music to the public became clear to Edison, he had his company begin recording and selling cylinders of musical performances. These cylinders, at the beginning, were not made with the intention to be sold to the public, but rather to be played on commercial phonographic machines, like jukeboxes. Even after he began pursuing a mass market for prerecorded music, however, his vision of the true potential of the phonograph seems to have faltered: he oversaw his company's selection of performers, and his library of musical choices was notoriously conservative and uninspired, and he later resisted using the technical innovation of electric recording via a microphone, continuing to use the process of acoustic recording, which required performers to play and sing into a wooden horn that mechanically focused the sound onto the needle that cut the groove in the master cylinder. He also resisted switching from cylinders to discs until 1913, well after other manufacturers had made the switch. [Question 2] Edison pursued one of the more seemingly trivial applications of the phonograph that he mentioned in his article—the manufacturing of talking dolls. An 1890 article in Scientific American describes a trip to the Edison Company's plant in Orange, New Jersey.[4]

[Question 2] Edison pursued one of the more seemingly trivial applications of the phonograph that he mentioned in his article—the manufacturing of talking dolls. An 1890 article in Scientific American describes a trip to the Edison Company's plant in Orange, New Jersey.[4] The article described a scene in the factory, which must strike a modern reader as strange: This engraving shows the manner of preparing the wax-like records for the phonographic dolls. They are placed upon an instrument very much like an ordinary phonograph, and in the mouth of which a girl speaks the words to be repeated by the doll. A large number of these girls are continually doing this work. Each one has a stall to herself, and the jangle produced by a number of girls simultaneously repeating, "Mary had a little lamb," "Jack and Jill," "Little Bo-peep," and other interesting stories is beyond description. These sounds united with the sounds of the phonographs themselves when reproducing the stories make a veritable pandemonium.

The article described a scene in the factory, which must strike a modern reader as strange: This engraving shows the manner of preparing the wax-like records for the phonographic dolls. They are placed upon an instrument very much like an ordinary phonograph, and in the mouth of which a girl speaks the words to be repeated by the doll. A large number of these girls are continually doing this work. Each one has a stall to herself, and the jangle produced by a number of girls simultaneously repeating, "Mary had a little lamb," "Jack and Jill," "Little Bo-peep," and other interesting stories is beyond description. These sounds united with the sounds of the phonographs themselves when reproducing the stories make a veritable pandemonium.

The University of Georgia's

The University of Georgia's