[Question 1] Tobacco was well known in England before the colonization of Virginia. The Spanish had introduced tobacco to Europe after their earliest voyages to the Caribbean and South America. It had reached England by 1565, when Sir Walter Raleigh acquired the habit of pipe smoking and introduced the English to tobacco. At that time, Spain dominated the new tobacco trade. When the Jamestown colonists arrived in Virginia, there was already a robust British and European demand for tobacco.

The Jamestown colonists first attempted to cultivate the variety of tobacco that was native to Virginia, Nicotiana rustica. But this was harsher and therefore inferior to Nicotiana tabacum, the Caribbean variety that the Spanish had made popular in Europe. In 1612 Englishman John Rolfe brought to the Virginia colony seeds of the milder, "sweet-scented" variety from the West Indies. In the Virginia soil, the seed produced a highly pleasant tobacco whose smoking qualities exceeded that which was grown elsewhere.

[Question 2] 30 acres out of 1000 was not unusual. The growing of tobacco enforced a complicated and stringent regimen on the grower. Weather, geography, and soil conditions had to be just right in order to achieve a good crop. All of these factors were present in the Tidewater region, which had fertile, loamy soil that suited the tobacco plant. The region had a relatively temperate climate and, in most years, received an ideal amount of rainfall. The land was also largely flat and most of it was accessible to the many waterways and tributaries that flowed into the Chesapeake Bay, ensuring relatively easy transport of the crop to the ships that would take it to England. For these reasons, the colonists found it "easy" to grow tobacco. Only seven years after John Rolfe shipped the first crop of Virginia-grown tobacco to England, it had become the colony's main export.

The tobacco plant, however, is quite temperamental and demanding. Even within a single field, the plant would be influenced by the amount of sunlight, minerals, water, and wind. Not all of the field would yield the best tobacco, even in years where there was neither too little rain nor too much. Also, growing tobacco rapidly exhausted the soil's nutrients. Without the addition of fertilizer, three years of growing tobacco was all it took to deplete the soil. The easiest solution was to have available large areas of cheap land so that the grower could shift his fields onto virgin soil when his original plot could no longer sustain his crop. At least in the first decades of the colonial settlements in the area, large tracts of cheap land were precisely what the colonists had, so this, too, made it "easy" for them to cultivate tobacco.

The tobacco plant, however, is quite temperamental and demanding. Even within a single field, the plant would be influenced by the amount of sunlight, minerals, water, and wind. Not all of the field would yield the best tobacco, even in years where there was neither too little rain nor too much. Also, growing tobacco rapidly exhausted the soil's nutrients. Without the addition of fertilizer, three years of growing tobacco was all it took to deplete the soil. The easiest solution was to have available large areas of cheap land so that the grower could shift his fields onto virgin soil when his original plot could no longer sustain his crop. At least in the first decades of the colonial settlements in the area, large tracts of cheap land were precisely what the colonists had, so this, too, made it "easy" for them to cultivate tobacco.

The tobacco planter also needed to have some portion of his land in forest because a large amount of lumber went into making the large barrels or hogsheads in which the tobacco crop was shipped, as well as for constructing his drying barns, cold frames, and drying rods, and for fueling the carefully kept fires in the barns that cured the harvested leaves.

Finally, besides the other factors already mentioned that limited the suitable acreage, the larger the plantation was, the larger was the labor force that was needed, and so additional acres of the plantation also had to be devoted to growing the food that the laborers would eat.

[Question 3] About 2 acres of cleared land, with each acre producing about 5,000 plants. This would require bending over about 50,000 times per growing season. One peculiarity of growing tobacco was the extraordinary amount of labor that was required. Unlike other crops, tobacco requires steps in its cultivation that stretch throughout almost the entire year. And many of these steps require intensive, but delicate, and incessant attention by the grower—preparing the beds, sowing the seeds in cold frames, transplanting the seedlings to hilled rows (all this, it was said, was a process as elaborate as making a lace pillow-case), making almost daily passes through the field to carefully pinch off suckers, pinch back the tops, pick off tobacco hornworms by hand, and harvest the leaves as they matured. The leaves then had to be strung on poles and put in drying barns to cure, where ventilation had to be constantly adjusted and small drying fires constantly watched. Afterwards, the leaves had to be taken down, sorted by size and quality, allowed to become slightly moist to make them pliable again, and packed into hogsheads for shipping out.

[Question 4] 50% or a little more of his wealth was typically in the value of his slaves. By 1700, Virginians were importing huge numbers of slaves to work the tobacco fields (it had begun eighty years before), creating what was for some a lucrative "subsidiary" trade, apart from trade in tobacco itself. As large landholdings became rarer, the nature of tobacco cultivation encouraged the increasing numbers of white farmers who could now only rent land to invest in slaves rather than land: Because the soil would be depleted in just a few years, it made sense to the farmer to invest his capital in the labor he could move to the next plot of rented land that he occupied, rather than in the soon-to-be exhausted land itself.

[Question 5] In some areas slave populations grew from 7% (in 1690) to 35% of the region's population in 1750. It rose to about 40% by the eve of the Civil War.

[Question 6] The colonists couldn't do anything with tobacco (beyond what they smoked themselves) except sell it—they couldn't eat it or feed it to livestock or use it in construction. It was only good for converting into cash, which seemed like a very good thing when they could essentially grow "cash" in their back yards and use it to purchase other things they needed, or to pay taxes or fines. Because there was almost nothing else that the colonists could export to England that the mother country could not produce itself (and of better quality), tobacco was doubly useful to the colonists. Very early on, tobacco became fixed as the stable value of other goods, replacing gold or silver in a culture where they were scarce.

With the very rapid growth of tobacco cultivation in the colonies, however, in just a few years there was too much tobacco being grown and prices for tobacco began to drop. Disruptions in the market in Europe, such as caused by the Thirty Years' War, also contributed to a glut and, consequently, much lower prices. One such price fluctuation in 1660 drove many Tidewater tobacco growers close to bankruptcy. The colonists responded with attempts to limit tobacco production and to ensure the high quality of all the tobacco that was shipped with public warehouses, inspectors, and licensed agents.

Nevertheless, all these measures amplified the amount of control exercised over the tobacco trade. This was a colonial, "mercantile" system, whereby the colonists were required to sell their crop only to England. In return, the growers were "protected" in some ways, but only as long as they continued to supply the crop. Many growers, by the beginning of the 18th century, felt trapped by the system, and looked for ways out of it, such as trying to diversify their crops, or to free their slaves, or to develop trade in other goods, or to develop manufacturing. Yet they needed capital in order to do this, which they could only get by selling tobacco. The dilemma they faced in all this suggested to many of them that the colonies would be better off if they were independent from England.

advances led to the rise of developments around cities. Streetcars, trains, and, later, highways made it possible for workers to commute to urban centers for work and to travel outside of the city for their home life. Suburb development grew exponentially after World War II with the rapid spread of mass-produced housing such as Levittown.

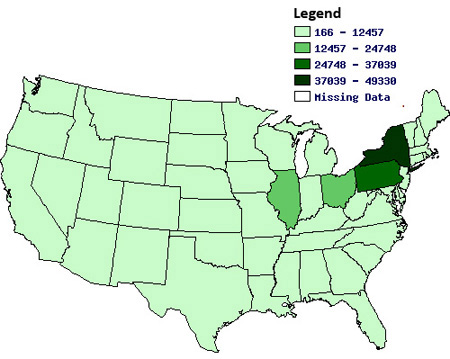

advances led to the rise of developments around cities. Streetcars, trains, and, later, highways made it possible for workers to commute to urban centers for work and to travel outside of the city for their home life. Suburb development grew exponentially after World War II with the rapid spread of mass-produced housing such as Levittown. Americans met their needs by harvesting energy and materials from plants, animals, rivers, and wind. By the 1830s, though, large-scale coal extraction had begun in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and beyond. By the 1910s, more than 750,000 coal miners dug and blasted upwards of 550 million tons of coal a year. Fossil fuels changed daily life in America, from travel to shopping, daily life to leisure. America's industrial ascendancy, however, caused problems for humans and the environment and in 2009, the threat of diminishing supplies is a serious concern.

Americans met their needs by harvesting energy and materials from plants, animals, rivers, and wind. By the 1830s, though, large-scale coal extraction had begun in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and beyond. By the 1910s, more than 750,000 coal miners dug and blasted upwards of 550 million tons of coal a year. Fossil fuels changed daily life in America, from travel to shopping, daily life to leisure. America's industrial ascendancy, however, caused problems for humans and the environment and in 2009, the threat of diminishing supplies is a serious concern.

The map of the 1920 concentration of manufacturing establishments was generated by the University of Virginia Library's

The map of the 1920 concentration of manufacturing establishments was generated by the University of Virginia Library's

The tobacco plant, however, is quite temperamental and demanding. Even within a single field, the plant would be influenced by the amount of sunlight, minerals, water, and wind. Not all of the field would yield the best tobacco, even in years where there was neither too little rain nor too much. Also, growing tobacco rapidly exhausted the soil's nutrients. Without the addition of fertilizer, three years of growing tobacco was all it took to deplete the soil. The easiest solution was to have available large areas of cheap land so that the grower could shift his fields onto virgin soil when his original plot could no longer sustain his crop. At least in the first decades of the colonial settlements in the area, large tracts of cheap land were precisely what the colonists had, so this, too, made it "easy" for them to cultivate tobacco.

The tobacco plant, however, is quite temperamental and demanding. Even within a single field, the plant would be influenced by the amount of sunlight, minerals, water, and wind. Not all of the field would yield the best tobacco, even in years where there was neither too little rain nor too much. Also, growing tobacco rapidly exhausted the soil's nutrients. Without the addition of fertilizer, three years of growing tobacco was all it took to deplete the soil. The easiest solution was to have available large areas of cheap land so that the grower could shift his fields onto virgin soil when his original plot could no longer sustain his crop. At least in the first decades of the colonial settlements in the area, large tracts of cheap land were precisely what the colonists had, so this, too, made it "easy" for them to cultivate tobacco.