1. The term "Jim Crow" originally referred to:

b. A popular burlesque song and theatrical dance number

White actor, singer, and dancer, Thomas D. Rice, wrote and performed "Jim Crow" (sometimes called "Jump Jim Crow" because of the first line of the chorus) in 1829 or 1830. To perform the song, Rice dressed in tattered rags and frolicked comically to impersonate a very low caricature of a black man. His performances became an overnight sensation among white audiences, and he performed all over the country. He then took his act to Britain and France, where it became an even bigger hit.

White actor, singer, and dancer, Thomas D. Rice, wrote and performed "Jim Crow" (sometimes called "Jump Jim Crow" because of the first line of the chorus) in 1829 or 1830. To perform the song, Rice dressed in tattered rags and frolicked comically to impersonate a very low caricature of a black man. His performances became an overnight sensation among white audiences, and he performed all over the country. He then took his act to Britain and France, where it became an even bigger hit.

One dismayed English drama critic in the London Satirist, however, wrote: "Talent is of no country, neither is folly; and were 'Jim Crow' of English creation, we should have assuredly dealt as severely with it as we have now done with the bantling of the new world--perhaps more so, for we would have strangled it in its birth to prevent it begetting any more of its own species to offend the world's eye with their repulsive deformities. The circumstance of its being an exotic, the production of the pestilential marshes of backwood ignorance, has had no effect with us in giving our opinion. There is no concealing the fact, that Jim Crow owes its temporary triumph in this country to one of those lapses of human nature which sometimes occurs, when the senses run riot, and a sort of mental saturnalia takes place." Quoted in "Jim Crowism," Spirit of the Times (New York), February 4, 1837.

2. "Jim Crow cars" were separate railway passenger cars in which blacks were forced to travel, instead of in the passenger cars in which whites took their seats. The term "Jim Crow cars" first came into use:

a. In the mid-1830s, in Massachusetts and Connecticut

Segregated public transportation began in the North before the Civil War. In many parts of the South, a black could not travel at all, unless he or she was accompanying (or accompanied by) a white, or carrying a pass from a white person.

Segregated public transportation began in the North before the Civil War. In many parts of the South, a black could not travel at all, unless he or she was accompanying (or accompanied by) a white, or carrying a pass from a white person.

The inconsistencies themselves bred conflict. One Massachusetts newspaper editor wrote, "South of the Potomac, slaves ride inside of stage-coaches with their masters and mistresses—north of the Potomac they must travel on foot, in their own hired vehicles, or in the 'Jim Crow' car. … What a black man is, depends on where he is. He has no nature of his own; that depends upon his location. Moreover the contradictions that appertain to him, produce corresponding contradictions in the white man. … Seriously, very seriously—do not the incongruities, the strange anomalies, in the condition of the coloured race, clearly show there is terrible wrong somewhere? … The confusion of tongues is terrible; the confusion of ideas is worse." From "Incongruities of Slavery," The Friend, March 26, 1842, quoting the [Worcester] Massachusetts Spy.

3. Among the very first deliberate African American challengers to Jim Crow practices in public transportation was:

b. Frederick Douglass, who refused, in 1841, to give up the first-class seat on the Eastern Railroad he took when he boarded the train at Newburyport, MA, and move to the train's Jim Crow car

Douglass may not have been the very first, but he appears to have been one of the first. African Americans in New England, beginning in late 1839, along with white abolitionists, with some successes, deliberately challenged extra-legal but fairly common Jim Crow accommodations on railroads, on stagecoaches, in churches ("Negro pews"), and in schools. The persistence of Jim Crow practices in the North, however, gave Southern slave-holding whites the opportunity to reproach even abolitionist Northern whites for "not treating their free blacks better."

Douglass may not have been the very first, but he appears to have been one of the first. African Americans in New England, beginning in late 1839, along with white abolitionists, with some successes, deliberately challenged extra-legal but fairly common Jim Crow accommodations on railroads, on stagecoaches, in churches ("Negro pews"), and in schools. The persistence of Jim Crow practices in the North, however, gave Southern slave-holding whites the opportunity to reproach even abolitionist Northern whites for "not treating their free blacks better."

4. After the Civil War, the practice of formally segregating whites and blacks working in Federal Government offices was instituted during the administration of which U.S. President?

c. Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson, who had been born in Virginia, soon after he took office in 1913, began a government-wide segregation of blacks and whites in Federal workplaces, restrooms, and lunchrooms. The policy appears to have been instituted after Wilson's Georgia-born wife Ellen visited the Bureau of Printing and Engraving in Washington and "saw white and negro women working side by side." Wilson's Secretary of the Treasury, William McAdoo (also Georgia-born, and soon to be the Wilsons' son-in-law) took the hint. Shortly thereafter, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury John Skelton Williams issued an order segregating the races in the Bureau. A Washington-wide order, covering all Government offices, followed, and soon all Federal offices everywhere in the country were covered by the same order.

Woodrow Wilson, who had been born in Virginia, soon after he took office in 1913, began a government-wide segregation of blacks and whites in Federal workplaces, restrooms, and lunchrooms. The policy appears to have been instituted after Wilson's Georgia-born wife Ellen visited the Bureau of Printing and Engraving in Washington and "saw white and negro women working side by side." Wilson's Secretary of the Treasury, William McAdoo (also Georgia-born, and soon to be the Wilsons' son-in-law) took the hint. Shortly thereafter, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury John Skelton Williams issued an order segregating the races in the Bureau. A Washington-wide order, covering all Government offices, followed, and soon all Federal offices everywhere in the country were covered by the same order.

White actor, singer, and dancer, Thomas D. Rice, wrote and performed "Jim Crow" (sometimes called "Jump Jim Crow" because of the first line of the chorus) in 1829 or 1830. To perform the song, Rice dressed in tattered rags and frolicked comically to impersonate a very low caricature of a black man. His performances became an overnight sensation among white audiences, and he performed all over the country. He then took his act to Britain and France, where it became an even bigger hit.

White actor, singer, and dancer, Thomas D. Rice, wrote and performed "Jim Crow" (sometimes called "Jump Jim Crow" because of the first line of the chorus) in 1829 or 1830. To perform the song, Rice dressed in tattered rags and frolicked comically to impersonate a very low caricature of a black man. His performances became an overnight sensation among white audiences, and he performed all over the country. He then took his act to Britain and France, where it became an even bigger hit. Segregated public transportation began in the North before the Civil War. In many parts of the South, a black could not travel at all, unless he or she was accompanying (or accompanied by) a white, or carrying a pass from a white person.

Segregated public transportation began in the North before the Civil War. In many parts of the South, a black could not travel at all, unless he or she was accompanying (or accompanied by) a white, or carrying a pass from a white person. Douglass may not have been the very first, but he appears to have been one of the first. African Americans in New England, beginning in late 1839, along with white abolitionists, with some successes, deliberately challenged extra-legal but fairly common Jim Crow accommodations on railroads, on stagecoaches, in churches ("Negro pews"), and in schools. The persistence of Jim Crow practices in the North, however, gave Southern slave-holding whites the opportunity to reproach even abolitionist Northern whites for "not treating their free blacks better."

Douglass may not have been the very first, but he appears to have been one of the first. African Americans in New England, beginning in late 1839, along with white abolitionists, with some successes, deliberately challenged extra-legal but fairly common Jim Crow accommodations on railroads, on stagecoaches, in churches ("Negro pews"), and in schools. The persistence of Jim Crow practices in the North, however, gave Southern slave-holding whites the opportunity to reproach even abolitionist Northern whites for "not treating their free blacks better." Woodrow Wilson, who had been born in Virginia, soon after he took office in 1913, began a government-wide segregation of blacks and whites in Federal workplaces, restrooms, and lunchrooms. The policy appears to have been instituted after Wilson's Georgia-born wife Ellen visited the Bureau of Printing and Engraving in Washington and "saw white and negro women working side by side." Wilson's Secretary of the Treasury, William McAdoo (also Georgia-born, and soon to be the Wilsons' son-in-law) took the hint. Shortly thereafter, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury John Skelton Williams issued an order segregating the races in the Bureau. A Washington-wide order, covering all Government offices, followed, and soon all Federal offices everywhere in the country were covered by the same order.

Woodrow Wilson, who had been born in Virginia, soon after he took office in 1913, began a government-wide segregation of blacks and whites in Federal workplaces, restrooms, and lunchrooms. The policy appears to have been instituted after Wilson's Georgia-born wife Ellen visited the Bureau of Printing and Engraving in Washington and "saw white and negro women working side by side." Wilson's Secretary of the Treasury, William McAdoo (also Georgia-born, and soon to be the Wilsons' son-in-law) took the hint. Shortly thereafter, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury John Skelton Williams issued an order segregating the races in the Bureau. A Washington-wide order, covering all Government offices, followed, and soon all Federal offices everywhere in the country were covered by the same order.

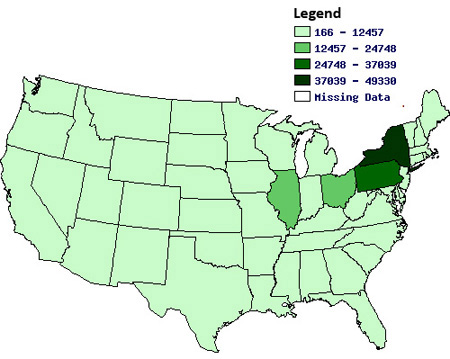

The map of the 1920 concentration of manufacturing establishments was generated by the University of Virginia Library's

The map of the 1920 concentration of manufacturing establishments was generated by the University of Virginia Library's

The statue stands in Kelly Ingram Park in Birmingham, AL. The park, which predates the civil rights movement, was used by Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) as a staging point for nonviolent protests in 1963. Protesters, many of them local schoolchildren, massed here to organize for sit-ins, boycotts, and marches; in the streets around the park, law enforcement officers drenched protestors with fire hoses and menaced them with dogs. Photographs of these events created some of the most enduring images of the movement.

The statue stands in Kelly Ingram Park in Birmingham, AL. The park, which predates the civil rights movement, was used by Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) as a staging point for nonviolent protests in 1963. Protesters, many of them local schoolchildren, massed here to organize for sit-ins, boycotts, and marches; in the streets around the park, law enforcement officers drenched protestors with fire hoses and menaced them with dogs. Photographs of these events created some of the most enduring images of the movement.  The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Park in Seattle, WA, honors the memory of King with an abstract sculpture inspired by his final speech, "I've Been to the Mountaintop." No specific event in the civil rights movement or in King's life took place at this location; like memorials, events, and other observances nationwide, the Memorial Park sculpture, by Seattle artist Robert Kelly, reminds the surrounding community not of specific historical events but of the assumed spirit of King's life and of the civil rights movement.

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Park in Seattle, WA, honors the memory of King with an abstract sculpture inspired by his final speech, "I've Been to the Mountaintop." No specific event in the civil rights movement or in King's life took place at this location; like memorials, events, and other observances nationwide, the Memorial Park sculpture, by Seattle artist Robert Kelly, reminds the surrounding community not of specific historical events but of the assumed spirit of King's life and of the civil rights movement. Sculptor Patrick Morelli's BEHOLD stands in the Peace Plaza in Atlanta, GA. Around the plaza range sites important in the life of Martin Luther King, Jr., including his birth home and Ebenezer Baptist Church, where King preached as co-pastor with his father. Newer sites also surround the statue and plaza: The King Center, the location of King's tomb, founded by King's widow, Coretta Scott King, and the Martin Luther King, Jr. Visitor Center, maintained by the National Park Service.

Sculptor Patrick Morelli's BEHOLD stands in the Peace Plaza in Atlanta, GA. Around the plaza range sites important in the life of Martin Luther King, Jr., including his birth home and Ebenezer Baptist Church, where King preached as co-pastor with his father. Newer sites also surround the statue and plaza: The King Center, the location of King's tomb, founded by King's widow, Coretta Scott King, and the Martin Luther King, Jr. Visitor Center, maintained by the National Park Service. The Martin Luther King, Jr., National Memorial does not yet exist, but the memorial's design has been completed and ground broken, ceremonially, on the proposed site. When finished, the envisioned four-acre memorial will be positioned along the edge of the Tidal Basin, along a sightline stretching from the Lincoln Memorial to the Jefferson Memorial. Difficulties and controversy have dogged the memorial's progress, including backlash when Chinese sculptor Lei Yixin was chosen to carve the nearly-three-story-tall statue of King that will anchor the memorial.

The Martin Luther King, Jr., National Memorial does not yet exist, but the memorial's design has been completed and ground broken, ceremonially, on the proposed site. When finished, the envisioned four-acre memorial will be positioned along the edge of the Tidal Basin, along a sightline stretching from the Lincoln Memorial to the Jefferson Memorial. Difficulties and controversy have dogged the memorial's progress, including backlash when Chinese sculptor Lei Yixin was chosen to carve the nearly-three-story-tall statue of King that will anchor the memorial. The National Park Service's travel itinerary

The National Park Service's travel itinerary