What is it?

Housing disparity is still a challenge many people, including students, face today. This guide provides historical context and primary sources so that students can better understand housing issues in the present-day U.S.

Key points:

- This activity will take one 90-minute period or two 45-minute periods. It is appropriate for a high school U.S. history classroom, but the sources can also inform a government class looking at the policy issue of housing.

- Students will analyze, interpret, and evaluate primary sources related to housing.

- Students will gain a better understanding of the defining characteristics of housing and the historical actors and policies that determine these factors

- Guiding Question: How has housing been provided for people in the U.S. and how has that changed over time?

Introduction

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, initially enacted in 1987 but reauthorized in 2015, ensures that youth facing homelessness can still access quality education and provides resources and assistance for students facing homelessness to succeed in their education. While there is a consensus that education is a fundamental right, housing is still an issue under debate. The purpose of this lesson is to indicate that the concept of housing as a basic right has changed over time. Students should take away that access to housing has not been solely based on individual actions or motives. It is based on various people, laws, ideas, and institutions.

This lesson aims to provide students with an understanding of the defining characteristics of housing and the historical actors and policies that determine these factors. The students should begin formulating the lesson's introduction about the foundations of a home. Have students think about what made those individuals’ houses homes. Another critical objective that teachers should have students think about is the interrelatedness of housing and houselessness. As the lesson will illustrate, housing development is usually coupled with the displacement of groups of people. This should prompt students to think about what happens to individuals when they are removed from places. To explore this interdependency of housing and houselessness, it is best to look at housing reform, which was emphasized during the New Deal. Educators should briefly reference the Great Depression and economic crisis to provide students with a starting point on how housing reform and public housing shifted into the present. The New Deal era demonstrates that concerns surrounding housing and the response to those concerns are displayed through policy and legislation. The reaction to those policies and legislation is through activism and lobbying. By the end of the lesson, students should be able to comprehend this cycle of development and reform, along with its various actors.

Background/Context

While housing has been an issue throughout history, the first federal action to address housing came as a response to the Great Depression in the 1930s. The Great Depression brought about a massive housing crisis and high unemployment rates across the United States. Progressive reformers, as a response, initiated housing reform. The U.S. Housing Act of 1937 provided government funding to build regulated public housing, creating affordable living arrangements for low-income citizens. These new housing structures had racial segregation embedded in their design and coupled with urban renewal initiatives, the deterioration of public housing initiatives would begin after World War II. The Great Migration brought many African Americans to urban areas in the Northeast, West, and Midwest, searching for new opportunities. Due to the increasing number of African Americans in the urban centers and changes in legislation such as Brown v. Board in 1954 and the soon-to-come Civil Rights Act of 1964, housing authorities could no longer preserve the separatist vision of their progressive architects. Policymakers and white residents began to use de facto methods to maintain segregation. Leaving public housing areas in droves as a response, creating a need for more suburban neighborhoods designed to maintain segregation. Additionally, federal subsidies could no longer support the costs of maintaining these public housing buildings. As a result of tenant rent adjustments, housing authorities could no longer sustain quality conditions for tenants, and these buildings often became neglected.

The 1970s and 1980s ushered in significant changes to housing policy in the United States. Concerns about private versus public funding for public housing and a resurgence in attention to homelessness created new policies that shifted American perspectives across racial and class lines. In the 1970s, urban renewal initiatives and policies such as the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 shifted funding for affordable housing from federal responsibility to corporate opportunity. This act established Section 8 housing, which provided housing vouchers that allowed low-income individuals to get government subsidies to live in privately owned properties. However, because of this new shift, many public housing buildings were neglected, and many African Americans and other minority groups, like Latino communities, were still residing in them. In the late 1970s and 1980s, there was an effort to move these residents out of public housing and into new privately owned neighborhoods. The 1986 Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) incentivized private developers to build new housing developments regulated by the state but relieved the federal government from fiscal responsibility. These initiatives, while alleviating the responsibility of the state and federal governments, did not lessen the ongoing poverty issues. By the 1990s, the HOPE VI program was created by Congress to demolish abandoned and neglected public housing and create new “mixed-income” housing developments.

Throughout these efforts, the demolishing of housing and the creation of new neighborhoods always come with the displacement of people. These efforts not only created housing opportunities but also created homelessness. During the 1960s and 1970s, there were areas of placeless people, commonly known as “skid row.” These areas were filled with liquor stores, poorly managed hotels, crime, and disorder. During the 1950s and 1960s, homelessness and these areas were mainly populated by males, but as policy changed over time, there was a rise in women and children facing homelessness in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1987, the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness was created to respond to these changes in homelessness. Continuing these efforts in the 1990s and early 2000s, advocacy increased in combatting homelessness. Many non-profit organizations were forming to relieve issues concerning homelessness and federal policy, such as the Homeless Emergency Assistance Transition to Housing Act, enacted in 2009, to provide funding for homelessness prevention and re-housing. Place and placeness are interdependent. Examining housing and homelessness in the history of the United States involves examining policies, the individuals who create them, and the individuals who are affected by them.

Activity

Bell Ringer

To begin the lesson, students should consider the foundational elements of what constitutes a home. Using a textbook, a selection of reference materials, or even an internet search have students find examples of different homes throughout history; think of Indigenous housing structures, homes of the settlers-colonists during the Westward expansion, or the elaborate houses built by the elite class during the Gilded Age. Students should be able to express commonalities and indicators of defining “home” by the end of the discussion.

Educators should allow students to consider whether housing structures are defined by their permanence and sustainability. Have students name the factors that could have led to temporary housing during earlier periods in U.S. history, such as migrating due to low food sources or natural disasters like fires or floods. There could also have been a lack of safety. Educators should guide students to determine that these first livable structures were built out of a necessity to survive, sheltering individuals and providing protection from elements that would compromise safety. Their permanence was yet to be determined.

Homes began to form when people had the proper devices to ensure their structure could shield them from primary threats and cultivate sustenance. Examples are the ability to farm and raise animals. Most importantly, there was no longer a need to uproot quickly. Have students name a few activities individuals can do when they no longer must worry about these threats. Ask students what some ways these individuals could manage these threats are.

Another significant development in creating permanent housing was property rights and land claims. People began to obtain documentation, such as deeds and titles, contracts, and leases, to represent their residences legally. Due to this, housing is now codified, but the right to housing is still in question. Federal and state governments create policies on how these laws can be enforced. Prompt students to consider the difference between a right to housing versus a right to shelter.

After this brief discussion, this activity will allow students to begin rationalizing their definitions of what constitutes a home.

To clarify the exercise, offer definitions for home. Here are a few definitions:

Example:

A home is a permanent structure used for habitation, procured through legal processes.

Oxford Dictionary

House

- (noun) A building for human habitation, typically and historically one that is the ordinary place of residence.

Home

- (noun/adj.) A dwelling place is a person’s house or abode, the fixed residence of a family or household, and the seat of domestic life and interests.

There are many definitions of house and home. Michael Allen Fox’s chapter “The Many Faces of Home” in Home: A Very Short Introduction suggests that the definition of home depends on linguistics, region, and cultural norms. Fox concludes that the definition of home is flexible and dependent on circumstance. Educators that would like additional information on how to define home should reference Fox’s chapter.

For additional resources on defining home, Habitat for Humanity’s “What Does Home Mean to You” voices the definition of home through various perspectives. This resource can be used as a preliminary source for educators to tie in themes from the discussion.

Step One

First, ask the class: What do you think defines a home?

Step Two

As an entire class or in small groups, use the images below in the Primary Sources section and ask students what characteristics define these types of houses. These images can be printed and put on a board or provided to students. The images can also be projected on the board, or if students have their own digital devices (i.e., laptops, tablets, desktop computers), provide them the links and have them pull the images up on their devices. Students can work individually or in groups according to the teacher's preference.

Educators can arrange these images in any order; however, they should refrain from telling the students what category they would be placed in.

Step Three

Create a list on a whiteboard or have students in groups write down characteristics for each image they think creates a home. For example, in Image #1, students can identify that there are curtains and other items displaying that people reside in the residence.

Conclusion

During the activity, students have become the decision-makers on defining what constitutes a home. This is a common theme throughout the lesson: who defines housing, and who decides who gets to have housing? Historically, actors have been policymakers, activists, and legal apparatuses.

Housing and homelessness are determined by permanence, which is determined by legislation. Legislation establishes ownership and protects residents, enforcing codes and policies to ensure the structure is livable. The policies determine housing rights. Throughout the lesson, students should continue to inquire about how these rights change over time.

Ask students: Who decides what constitutes a home?

Primary Sources: Housing Examples

- Typical Housing in Greenbelt, Maryland- https://www.loc.gov/item/2018699737/

Annotation: These houses should be categorized as homes. Students should be able to identify residency in both homes by examining them. A satellite dish, curtains, and other identifiers provide proof of occupancy. The individual in this home is either the owner or renter, and the structure has gone through a legal process to become a permanent structure. Housing communities in the Greenbelt District were developed during the New Deal Era in 1935 under the United States Resettlement Administration. This administration was designed to resettle farmers and migrant workers affected by the Dust Bowl.

- One of Many Small Ponds Surrounded By Housing Developments in Gilbert, Arizona, a Southern Suburb of Phoenix, Arizona- https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2018702325/

Annotation: The homes in this picture are recently built. This picture was taken in 2018. Students should recognize that these are permanent structures and think about what these homes do to the environment and homes of other organisms. This picture shows a pond and clear signs of human manipulation of this environment. Teachers should guide students to conclude that homes that are this way permanently displace other living things and their habitats while creating new ones for others.

- Housing Development Around a Private Lake in the Northern Reaches of Indianapolis, Indiana- https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016631680/

Annotation: This image is an aerial view of housing development. Have students notice the exclusiveness of this property. It is essential to identify this lake as private. Some indicators show that there are very few entry points into this neighborhood. This is designed for the safety of the community. Students should reference the previous discussion that safety and community building are critical to creating permanence. Also, the concept of privatizing property, such as the lake, relates to the debate on property rights. This lesson will discuss the conversations between policymakers and citizens on whether housing initiatives should depend on government subsidies or become a private corporate venture. Students should begin to acknowledge the differences and outcomes between the two.

- Abandoned Public-Housing Units in the Liberty City Neighborhood of Miami, Florida- https://www.loc.gov/resource/highsm.62362/

Annotation: The housing units in this image were a government-subsidized public housing project built in the 1930s. The housing units, while no longer in use, are the physical representation of the changes in housing reform. These units were once heavily populated during the early stages of housing reform. However, they are vacant over time due to many policy changes.

Primary Source Analysis Activity: Housing Policy

To analyze these sources, divide students into groups and create a station for each primary source, a total of four stations that students will rotate. Students should spend 10 to 15 minutes at each station examining the sources, answering associated questions, and recording them on paper. Each group should have one document to share their answers at the end of this activity. The questions are designed to have students not only think about the material from a historical perspective but also prompt students to think about historical actors involved in creating housing policy changes and homeless assistance reforms. These sources are in chronological order to aid students in analyzing how housing changes over time. During this activity, ensure that students contemplate the relationship of each source and whether it adds to the continuity or change in housing policies and public sentiments. At the end of the activity, reassemble the class and discuss each group’s answers.

A computer or tablet will be needed for this activity.

Step One

To begin this activity, additional information should be provided to frame the required con, specifically with Sources #3 and #4, due to the nature of the sources. As the entire class, educators should review each source, provide background information, and review the specific questions on each source.

Step Two

Divide students into groups, set a timer for 10 minutes, and begin the timer at the start of each rotation. Each station should have instructions for the students, including how to use the source and the associated questions. Students should write a 3-5 sentence answer for each station’s question.

Step Three

After all student groups have completed the activity, the class should reconvene, review each question, and have students share their answers. Educators should revisit the information provided at the start of the activity as needed.

Station One

Educators should print out the Library of Congress’s Public Improvement map and use a computer or tablet to display Mapping Segregation DC’s “Restricted Housing and Racial Change, 1940-1970” map for students to interact.

Source #1

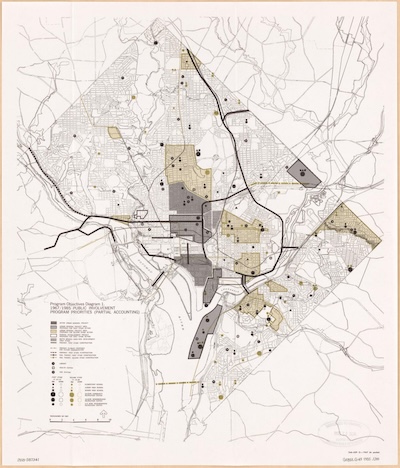

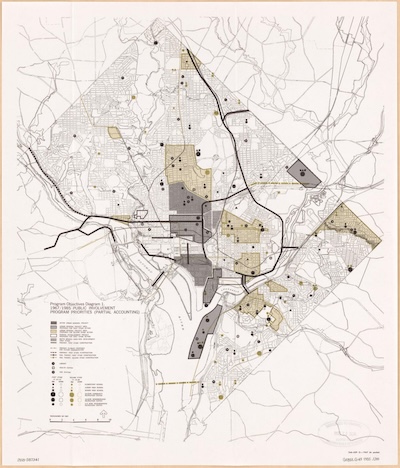

Program objectives diagram 1: 1967-1985 public improvement program priorities (partial accounting) : [District of Columbia]. - https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3851g.ct010988/?r=-0.279,0.116,1.856,0.957,0

This city-planning map displays urban renewal plans in Washington, D.C., created in 1967 to illustrate development plans from 1967-1985. This map shows where new schools will be built, transit systems, parks, and other infrastructure for public improvement. Have students pay attention to where these activities are located. In tandem with this source, have students examine Mapping Segregation DC’s, Restricted Housing and Racial Change, 1940-1970 map, and have students identify who lives in the neighborhoods that will be affected. Choose the layers of the map that coordinate with the time of this development plan. ‘

Questions

- What does “public improvement” mean according to this map?

- What places are being added to the neighborhood?

- What neighborhoods and residents are being affected based on both maps?

Station Two

Educators can print out this source or display it digitally.

Source #2

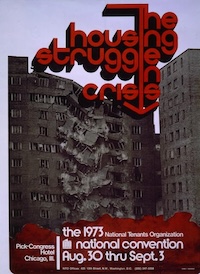

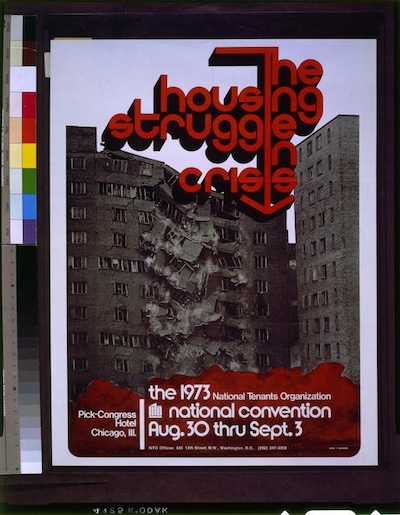

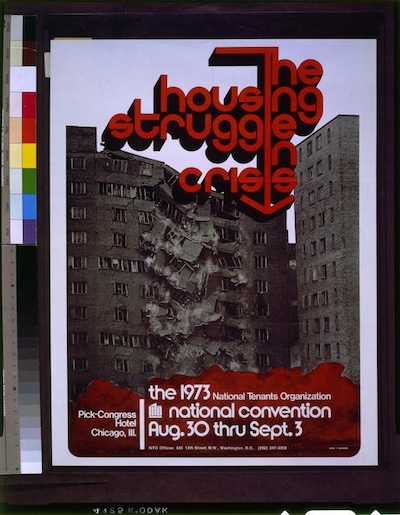

The Housing Struggle in Crisis, National Tenant Organization Poster, 1973- https://www.loc.gov/item/2016649888/

This source is a poster for the National Tenant Organization’s National Convention in 1973, held in Chicago, Illinois. The poster shows an apartment building being demolished. The National Tenant Organization was formed in 1969 to help with tenants' rights issues. The National Tenants Organization vs. HUD (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development) determined that HUD’s restriction in deductions to secondary wage earners resulted in overcharging those tenants. The courts determined that this was a violation and that HUD must carry out the deductions. Students examining this source should contemplate the types and levels of advocacy during housing reform.

Questions

- How does this poster depict issues surrounding housing during the 1970s?

Station 3

Educators should print or display digitally the first page of this source and highlight the excerpt or print out the excerpt of the source placed below.

Source #3

U.S. Reports: Hills, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development v. Gautreaux et al., 425 U.S. 284 (1976). - https://www.loc.gov/item/usrep425284/

Hills vs. Gautreaux was a defining moment in housing reform. This case shows that racial discrimination remained active after the 1964 Civil Rights Act. It prompted housing authorities to create new non-discriminatory housing programs, including Section 8 and integrating Black and White residents. Students should use the excerpt below, and educators should prompt a discussion about the magnitude of why the integration of residence was essential to Americans. This case is twelve years after the Civil Rights Act and in Chicago, which is often not associated with racism as in the American South. Students should identify that racism was nationwide and that the Civil Rights Act, a federal law, did not solve the problem of segregation. While segregation was now illegal, de facto segregation was still prevalent.

Excerpt:

“Respondents, Negro tenants in or applicants for public housing in Chicago, brought separate class actions against the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), alleging that CHA had deliberately selected family public housing sites in Chicago to ‘avoid the placement of Negro families in white neighborhoods’ in violation of federal statutes and the Fourteenth Amendment, and that HUD had assisted in that policy by providing financial assistance and other support for CHA's discriminatory housing projects. The District Court on the basis of the evidence entered summary judgment against CHA, which was ordered to take remedial action. The court then granted a motion to dismiss the HUD action, which meanwhile had been held in abeyance. The Court of Appeals reversed, having found that HUD had committed constitutional and statutory violations by sanctioning and assisting CHA's discriminatory program.”

Questions

- What does this case say about race in public housing during the 1970s?

Station 4

This station should center on the preservation of communities. Educators should be permanently present at this station to guide conversations and answer questions.

Source #4

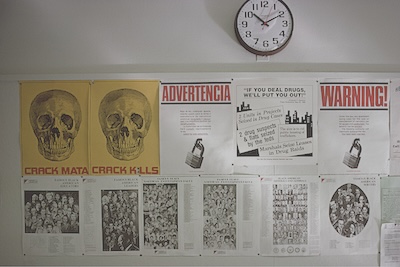

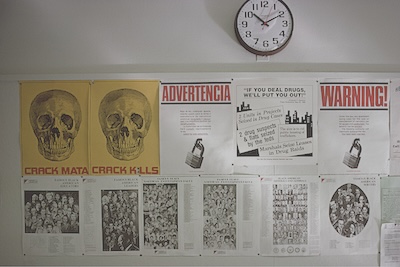

Bulletin board at Johnson Houses, E. 115th St. at Lexington Ave., Harlem, 1989 digital file from original- https://www.loc.gov/resource/vrg.07713/

This is a bulletin board in a public housing project in Harlem, NY. It is filled with advertisements about drug prevention and bulletins that encourage Black success. There is also a sign in Spanish. This primary source shows what some public housing communities faced during this time in these housing projects. This source also shows the dichotomy of the needs of Black and Brown community members. It shows the upliftment and success of the Black and Brown communities while protecting their communities from crime.

During the 1980s, many members of the public believed minority communities were responsible for crime and poor living conditions. The most crucial portion of this source is that it shows an effort of community members to preserve their communities so that they won’t be subjected to urban renewal initiatives. It is also essential for students to note that there wasn’t much improvement in housing between the 1960s and 1980s. Have students identify why that is.

Questions

- How do the posters on this bulletin board speak to the preservation of public housing in the 1980s?

Wrap Up

To conclude this lesson, have students reflect on the difficulty of decision-making and consider who determines housing and houselessness.

Revisit the question in the Bellringer exercise and discuss how answers may have changed or have stayed consistent.

Question: What defines housing? Who decides these defining attributes?

General Tips for Teaching Controversial Subjects

- Center activities on primary sources. Primary sources are tangible evidence that allow students to engage directly with history. These primary sources in particular were preserved and digitized by the Library of Congress because they were deemed important to the history of the United States.

- Discussion and analysis of these sources can be wide ranging, but within each class those discussions can always be turned back to the source itself.

- The sources are also, by definition, only pieces of a puzzle. They bring us closer to understanding the past but there is always room for doubt and uncertainty.

- Questions, Observations, and Reflections should come from students. These are primarily student-directed learning activities. It is the instructor's role to create a space for inquiry and empower students to drive the inquiry.

- It may help to remind students at the outset that it is normal for different individuals to come to different conclusions, even when we are looking at the same sources. Further, it would be strange if we all agreed completely on our interpretations. This can normalize the strong reactions that can come up and enables educators to discuss the goal of historical research, which is to hopefully go beyond the realm of individual perspective to access a fuller understanding of the past that takes multiple perspectives into account.

- Teaching historical topics that involve violence and other trauma can be traumatic for some students as well. Providing students with previews of what content will be covered and space to process their emotions can be helpful. The following video series from the University of Minnesota contains further tips for teaching potentially traumatic topics: https://extension.umn.edu/trauma-and-healing/historical-trauma-and-cultural-healing.