9/11 and Commemoration: A Guide for Pre-Service Teachers

What is it?

For students in high school today the events of September 11 belong to the past, but they may very likely encounter the yearly commemorations of those events on television or social media or they may have seen a physical memorial either in their area or while traveling. The past regularly enters our daily lives in this way and this is distinct from history. This guide explores commemorations, memorials, and monuments of the September 11 attacks to help students identify and recognize how they engage with the past how that process differs from history.

Key points:

- This activity will take one 90-minute period or two 45-minute periods. It is appropriate for a high school U.S. history classroom, but can be modified for a variety of learners.

- Students will analyze, interpret, and evaluate primary sources.

- Students will learn more about the events of September 11 and also how those events exist in public memory.

- Guiding Question: What's the purpose of commemorations and memorials

Introduction

History is the process by which we try to better understand the past, but history is not the only way human beings use the past or make meaning out of past events. This guide looks at another process of remembering the past through commemorations and memorials. Specifically it looks at the commemoration of and memorials to the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States in order to help students identify the differences between commemorating past events and studying those events historically. While the events of 2001 seem quite recent for some of us, they are far enough in the past to begin to be considered as history — especially for students in high school today who are too young to have been alive when these attacks occurred. Analyzing how various commemorations and memorials engage with the past will help students recognize the difference between this engagement and history while also understanding better the place the events of September 11, 2001 in public memory.

Hook/Bellringer

Write on the board: What is a commemoration? Can you think of examples?

If students are struggling with this prompt, add related words that they might be more familiar with such as “memorials” or “monuments”. Explain that memorials and monuments are specific kinds of commemorations. Have students come up with 5-10 examples of their own and have them note what event is being commemorated by the memorial.

Show the following images to prime their memory.

Washington Monument, Washington, D.C. | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2010641711

Aerial view of the Lincoln Memorial, Washington, D.C. | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2010630765

Memorial Day, Vietnam Memorial, Washington, D.C. | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2010630875

Note: Teachers may also want to include memorials and monuments from their community or region.

Background/Context

[This can be read to class, assigned for the class to read ahead of time, or you can substitute another resource such as the FAQ from the National 9/11 Memorial and Museum.]

On the morning of September 11, 2001, a group of 19 men forcibly took control of four separate commercial jet airliners. The first two planes struck each of the World Trade Center's Twin Towers [office buildings with more than 100 floors each] in New York City and a third aircraft struck the Pentagon — the headquarters for the U.S. Department of Defense — in Arlington, Virginia. A fourth aircraft crashed into an open field in Somerset County, Pennsylvania after the passengers and crew, having learned about the earlier attacks via phone calls they were able to make to family and friends, attempted to take control of the aircraft away from the attackers. In all 2,996 people died in the attacks. It was later learned that the attackers were associated with an extremist group, al Qaeda, then based in Afghanistan. The response from the U.S. government led to an invasion of Afghanistan from which troops were only withdrawn in 2021. The attack was also used to justify the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The attacks resulted in changes within the U.S as well, including new laws such as the 2001 Patriot Act, changes to airline security procedures, and even changes to the structure of the federal government with the creation of a new cabinet department, the Department of Homeland Security. The full effects of these attacks are still being felt today both in the U.S. and around the world.

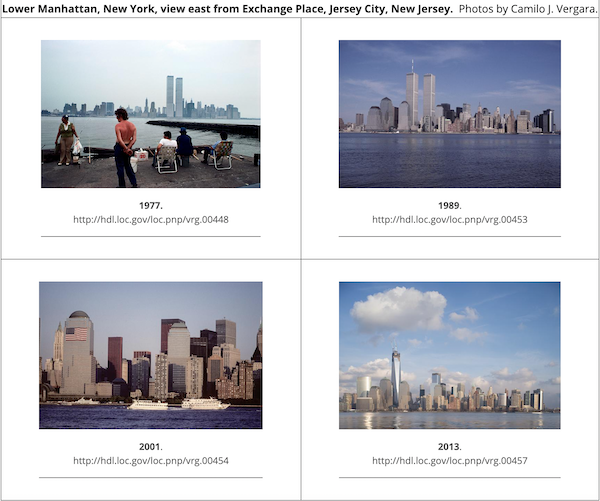

[While you read the above background, you may want to display the images in the blog post below that show the lower Manhattan skyline before and after the attacks.]

The World Trade Centers in an Evolving Skyline | Picture This | blogs.loc.gov/picturethis/2016/09/the-world-trade-centers-in-an-evolving-skyline/

Activity

Have your students examine the images below in the Primary Sources section. This can be done digitally with the links provided below or the sources can be printed out for students to examine physically. Each source is a photograph of a memorial to the September 11 attacks. The memorials come from different locations across the U.S. and were built at different times. Some are informal handmade memorials put in place immediately after the attacks. Others were planned monuments built several years later. Students should examine these sources closely and then work together to sort them into those memorials that were placed at the site of the attacks (either at the World Trade Center Towers in New York, the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, or the field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania). Students should then divide the photos into those that were placed in the immediate aftermath of the attacks (2001-2002) and those that were constructed later (after 2002). Students can make use of the information that accompanies the images on the Library of Congress page to make these determinations about time and location.

This sorting can be done physically with printouts on four tables or desks or digitally with platforms such as Google slides or Padlet.

Once these have been sorted, prompt students to look for patterns by examining the photos closely. Provide the following questions for students to consider as they examine the images:

- What if anything does the memorial communicate about the September 11 attacks?

- What themes do they express or communicate?

- Do they look similar to any other memorials you have seen? Which ones and in what way?

- How do the memorials and commemorations differ by time and location?

These questions could form the basis of a whole class discussion or students could discuss them in groups of 3-5 and report out. If the course is online students could post their responses in a discussion board in their LMS.

Optional Short Essay Assignment for homework (1-2 paragraphs)

What purpose do you think memorials and commemorations serve? What’s their purpose? How might historians engage with the events of September 11? What sources would they use to understand the event and its impact?

Primary Sources

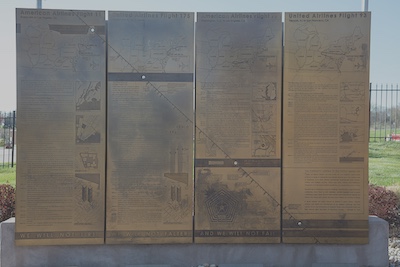

The 9/11 Memorial in Overland Park, Kansas, a Kansas City suburb, includes informational signs about the four aircraft destroyed, and their passengers killed, in the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York, the Pentagon in Washington, and in a hijacking over rural Pennsylvania by terrorists on September 11, 2001 | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2021756265/

Memorial to the brave souls of Flight 93 that crashed in Shanksville, Pennsylvania on September 11, 2001 after a terrorist attack. The plaque was donated by a private citizen named Hebert Erdmenger in 2002. | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2011631500/

Informal tributes posted at the first, temporary memorial site in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, to those who perished on United Flight 93, which crashed during an attempt by passengers to recapture the plane, which had been hijacked by terrorists on 9/11/01 | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2011633153/

Steel beam and rubble from the Twin Towers, displayed at the Milwaukee County War Memorial Center in Milwaukee, Wisconsin | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2016631019/

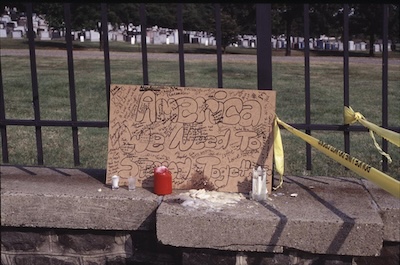

Citizen artwork at an informal memorial to the victims who died on United flight 93 when they attempted to overpower hijackers during the terrorist attacks of 9/11/2001 | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2011634321/

South Bend, Indiana's, 9/11 Memorial, erected by South Bend fire department personnel in St. Patrick's Park | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2016631954/

A piece of steel from the World Trade Center, destroyed by a terrorist attack on Sept. 11, 2001 in New York City. It is displayed as a memorial at the Texas State Cemetery in Austin, Texas| Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2014632438/

Memorial gate, where people from all over the world have left momentos to honor the victims of the September 11, 2001 terrorist hijacking of Flight 93. Shanksville, Pennsylvania| Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2011631553/

Part of an informal memorial to the victims of United Flight 93, which crashed in a nearby field after passengers fought with hijackers who had taken the plane and directed it to Washington during the terrorist attacks of 9/11/2001 | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2011633798/

Part of an informal memorial to the victims of United Flight 93, which crashed in a nearby field after passengers fought with hijackers who had taken the plane and directed it to Washington during the terrorist attacks of 9/11/2001 | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2011633961/

Portland, Maine's, modest memorial to those lost in the terrorist attacks on the United States on 9/11/2001, at Fort Allen Park at the busy harbor on Casco Bay in Maine's largest city | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2017882500/

A rusted steel beam recovered from New York City's fallen World Trade Center that fell during infamous terrorist attacks in 2001 stands at this "9/11" memorial in Gila Bend, Arizona. | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2018663482/

Calatrava's Oculus, a 335-foot-long, spiky-skylighted transportation hub attached to the One World Trade Center memorial in downtown Manhattan (borough) in New York City. The structure, designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava, opened on the 16th anniversary of the terrorist attack that brought down the World Trade Center's "Twin Towers" on what has become known simply as "9/11" - September 11, 2001| Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2018699939/

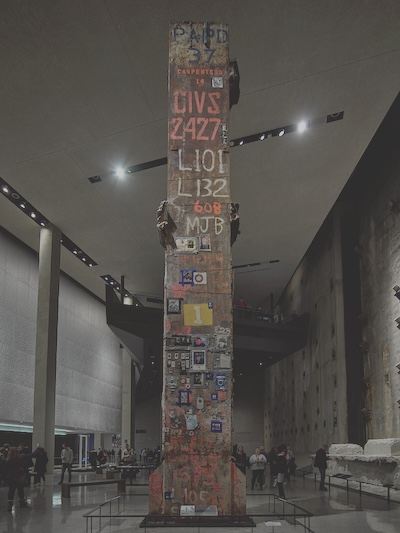

Interior view of the World Trade Center Memorial and Museum in downtown Manhattan (borough) in New York City, built on the site of the terrorist attack that brought down the World Trade Center's "Twin Towers" on what has become known simply as "9/11" - September 11, 2001 | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2018699980/

Interior view of the World Trade Center Memorial and Museum in downtown Manhattan (borough) in New York City, built on the site of the terrorist attack that brought down the World Trade Center's "Twin Towers" on what has become known simply as "9/11" - September 11, 2001 | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2018699981/

Memorial photograph wall of people killed at the World Trade Center Memorial and Museum in downtown Manhattan (borough) in New York City, built on the site of the terrorist attack that brought down the World Trade Center's "Twin Towers" on what has become known simply as "9/11" - September 11, 2001 | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2018700059/

Angel memorial near the Shanksville, Pa., crash site of United Airlines Flight 93, which was highjacked in the September 11th terrorist attacks | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2002717287/

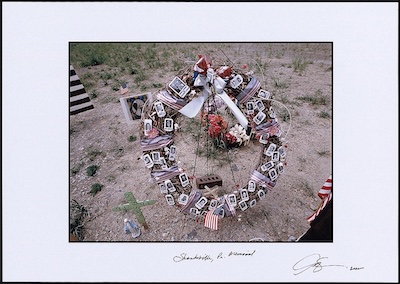

Wreath memorial, Shanksville, Pa., decorated with photographs of the victims of United Airlines Flight 93, which was highjacked in the September 11th terrorist attacks | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2002717288/

Sculptor Sassona Norton's 9/11 Memorial outside the Montgomery County Courthouse in Norristown, Pennsylvania The memorial honors those who died in the events of September 11, 2001, when terrorists attacked New York's World Trade Center, the Pentagon in Washington, and an airliner flying over Pennsylvania The memorial is cast in bronze and features a set of hands that hold a 16-foot piece of twisted steel from the wreckage of the Trade Center| Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2019689991/

A "9/11" memorial at Indiana University of Pennsylvania in the town of the same name, to those killed in three locations in terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001 | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2019691118/

The 93-foot "Tower of Voices" at the Flight 93 National Memorial near Shanksville, Pennsylvania | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/highsm/item/2019690759/

9/11 Memorial at the Pentagon, Pentagon City, Virginia | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2010630812/

Memorial at the Pentagon - Poster | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/afc911000188/

Memorial at the Pentagon-Marine Flag | Library of Congress | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/afc911000187/

Memorial at the Pentagon - Flag 2 | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/afc911000189/

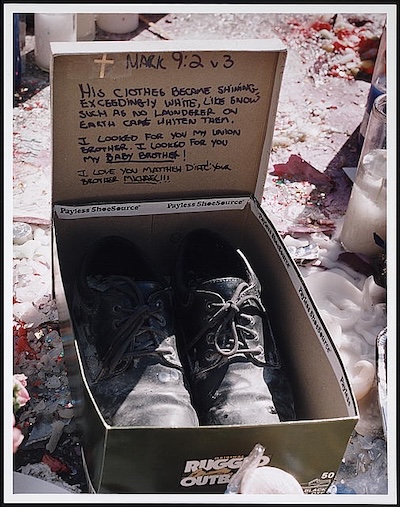

Memorial to Matthew Diaz, a victim of the September 11th terrorist attack on the World Trade Center, New York, N.Y. | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2002717256/

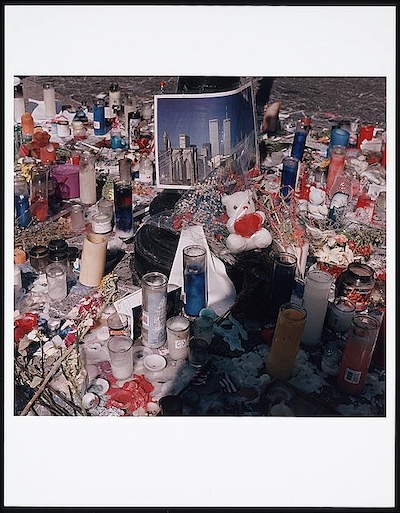

Memorial for the victims of the September 11th terrorist attack on the World Trade Center, New York City; with candles, flowers, mementos, and photo of the twin towers | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2002717255/

General Tips for Teaching Controversial Subjects

- Center activities on primary sources. Primary sources are tangible evidence that allow students to engage directly with history. These primary sources in particular were preserved and digitized by the Library of Congress because they were deemed important to the history of the United States.

- Discussion and analysis of these sources can be wide ranging, but within each class those discussions can always be turned back to the source itself.

- The sources are also, by definition, only pieces of a puzzle. They bring us closer to understanding the past but there is always room for doubt and uncertainty.

- Questions, Observations, and Reflections should come from students. These are primarily student-directed learning activities. It is the instructor's role to create a space for inquiry and empower students to drive the inquiry.

- It may help to remind students at the outset that it is normal for different individuals to come to different conclusions, even when we are looking at the same sources. Further, it would be strange if we all agreed completely on our interpretations. This can normalize the strong reactions that can come up and enables educators to discuss the goal of historical research, which is to hopefully go beyond the realm of individual perspective to access a fuller understanding of the past that takes multiple perspectives into account.

- Teaching historical topics that involve violence and other trauma can be traumatic for some students as well. Providing students with previews of what content will be covered and space to process their emotions can be helpful. The following video series from the University of Minnesota contains further tips for teaching potentially traumatic topics: https://extension.umn.edu/trauma-and-healing/historical-trauma-and-cultural-healing.

Have students search for topics both historical and contemporary, and see what the entries for the images they turn up say about copyright. "No known restrictions on publication?" "Unrestricted?" Images created before 1923 should be in the public domain, free of copyright restrictions, as should images created by government organizations. More recent sources may note copyright restrictions, including specific caveats about how a source may be reproduced.

Have students search for topics both historical and contemporary, and see what the entries for the images they turn up say about copyright. "No known restrictions on publication?" "Unrestricted?" Images created before 1923 should be in the public domain, free of copyright restrictions, as should images created by government organizations. More recent sources may note copyright restrictions, including specific caveats about how a source may be reproduced. Another informative stop might be Yahoo's

Another informative stop might be Yahoo's  Now that your students understand how tricky it may be to find sources that can be freely used to tell the story of history, they're in a position to help out, themselves! What historic sites or other traces of history exist in your local area? Are there Creative Commons-licensed images of these on, say, Flickr? If not, how about collecting some? Students can help fill in the gaps in our public record of place and time, and add to the resources available to students like themselves.

Now that your students understand how tricky it may be to find sources that can be freely used to tell the story of history, they're in a position to help out, themselves! What historic sites or other traces of history exist in your local area? Are there Creative Commons-licensed images of these on, say, Flickr? If not, how about collecting some? Students can help fill in the gaps in our public record of place and time, and add to the resources available to students like themselves.