Free Speech Teaching Guide 2: Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969): Defining and Arguing Hate Speech

This Teaching Guide is part of a series. Each of the four total teaching guides speaks to one aspect of the history of free speech. Although they work together to tell different parts of this history, it is not necessary to teach all of the guides or to teach them in a certain order. Each guide is a self-contained lesson.

(A PDF version of this teaching guide is also available for download-see left)

Other guides in the series:

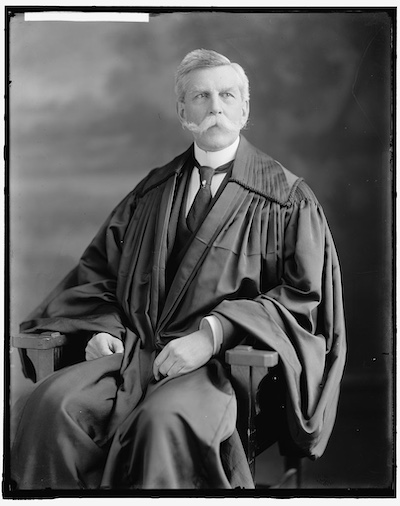

Free Speech Teaching Guide 1: The Birth of the Modern First Amendment: How Oliver Wendell Holmes Changed His Mind

Free Speech Teaching Guide 3: The Problem of National Security Secrets

Free Speech Teaching Guide 4: Mandel v. Kleindienst (1972): Censorship via Visa

Recommended for:

- 11th Grade US History

- 12th Grade Government

- Undergraduate History

Table of Contents

Guide Introduction:

This introduction briefly previews the how this guide will cover Brandenburg v. Ohio 1969 and why that case is useful in teaching students about the basic legal principles of free speech in the United States.

Classroom Activities:

Exercise 1: How to read a court case. A structured guide on how to explain the case to students and facilitate classroom conversation. Includes a link to the original case and relevant Constitutional Amendments.

Exercise 2: Thinking about free speech principles, not politics. A full-class group activity on the white board. What makes some forms of speech so "harmful" that they fall outside of the First Amendment's protection?

Exercise 3: What's the harm in hateful speech? An exercise intended to invite and address questions of how violence is defined. It includes questions alongside arguments in favor of either restricting or tolerating speech.

Appendix:

Excerpt of the Supreme Court's 1969 decision in Brandenburg v. Ohio to refer to during the Classroom Activities. The entire source (external) is linked here.

Guide Introduction

This case from the late 1960s, about the right of Ku Klux Klan members to call for racial violence, marks an important turning point in the law of free speech. The court firmly and finally rejected the notion that one could be punished for publicly advocating for a crime – closing the books on the long period in which left-wing advocacy for revolution had been criminalized. And it announced a new rule that was very protective of even the right to advocate for crime – a rule that still guides the law today, and that embodies, for many commentators, the essence of modern free speech law.

The case is therefore a good one to teach to show students the basics of free speech law. It is also a short decision issued by a unanimous court (rather than being signed by one judge, the decision was issued per curiam, or for the court, normally a sign that it is non-controversial). Leaving out the two concurrences, the decision runs for only about five pages, and its reasoning is fairly straightforward. It thus serves as a useful case to teach students how to read a supreme court decision.

This teaching guide includes:

- A structured guide to explaining the case to students

- A classroom exercise on the value of tolerating hateful speech

- A classroom exercise to think about the harms of hateful speech

Note: there are links throughout this guide to the end of the document where an appendix houses excerpts of the Supreme Court decision and an external link to the entire resource.

Classroom Exercise I: How to read a court case

Contents:

Overview

Introduction & Context

Hypotheticals

Final Context & Wrap Up

Overview:

This exercise will introduce students to the Brandenburg case itself and help them begin to grapple with its main debates. It works best as a whole classroom activity, although the reading may be assigned as homework to be reviewed before class. The goal of this lesson is for students to be able to draw connections between Brandenburg and the relevant constitutional amendments, as well as understand the complexity of free speech logic as seen in the case.

Introduction & Context:

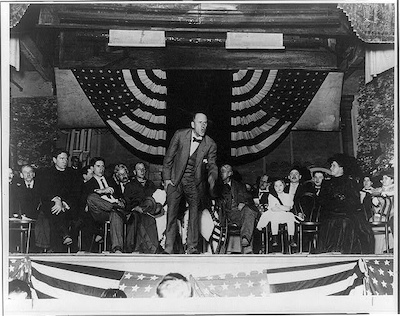

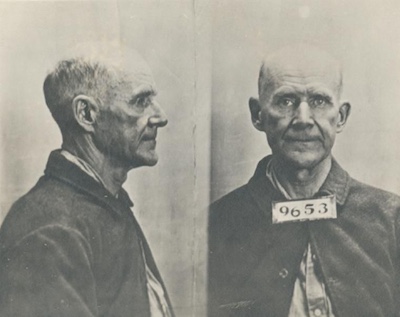

The place to begin is by having students read the decision and asking them to identify the facts in the case. This can be assigned as homework or conducted as a guided reading in the classroom. In clear prose, the court outlines the essential facts on pp.444-447 of the decision. The key details for students to grasp are that Clarence Brandenburg was a member of the KKK in Ohio, and late in the June of 1964 he was filmed at a meeting of about a dozen Klansmen making racist statements and suggesting that if the U.S. continues to “suppress the white, Caucasian race, it’s possible that there might have to be some revengeance taken.” He then proposed marching on Washington DC on July 4.

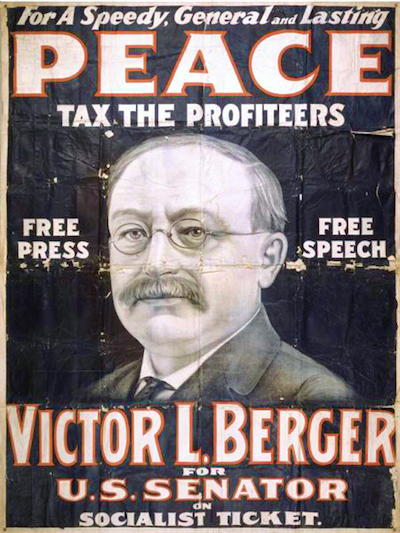

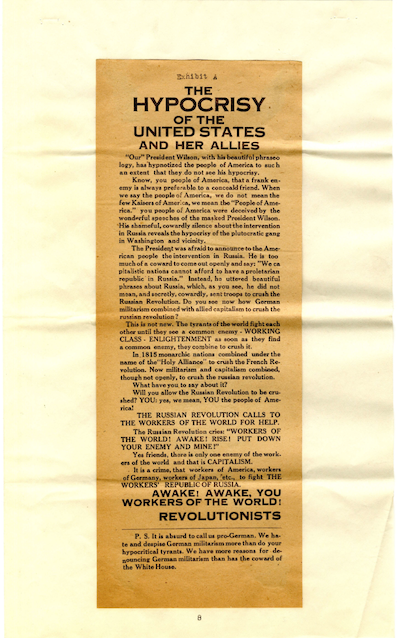

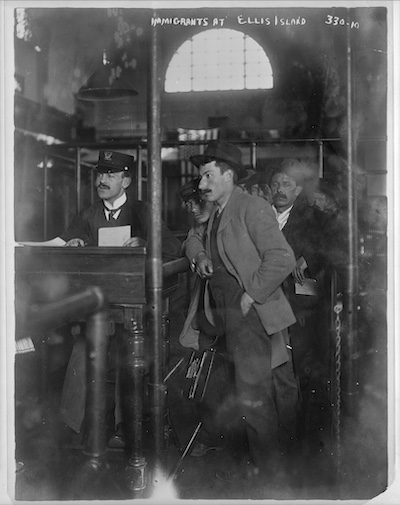

The next question is how Brandenburg was charged. The court tells us in the opening sentences of its decision – he was convicted under an Ohio Criminal Syndicalism statute for advocating the “duty, necessity or propriety” of crime or violence. The law dated from 1919, one of a series of state laws – 20, the courts tells us on p.447 – passed during the First Red Scare in an effort to criminalize revolutionary socialist and anarchist parties.

So what question is the Supreme Court answering in this case? Whether the Ohio Syndicalism law is constitutional, or whether it violates Brandenburg’s First and Fourteenth Amendment rights (p.444). The First Amendment issue is straightforward – he was sentenced to jail and fined for his speech.

But you might want to explain the 14th Amendment piece to your students, particularly if it is a more advanced class, or if you have spent time discussing federalism. The First Amendment says only that “Congress shall make no law”– in the 19th century, it was understood that it did not apply to state laws, like the Ohio law in question here, it only applied to the federal government. (To the extent that one wanted to challenge state laws, you had to rely on whatever bills of rights were included in state constitutions.) But beginning in the 1920s, the Supreme Court began to hold that the First Amendment did apply to the states – they did so by ruling that the 14th Amendment’s guarantees of “due process” included the First Amendment right to free speech and free press, and thus that the First Amendment applied to state as well as federal laws. This process is known as incorporation. One needn’t get into this with students unless they are curious – the upshot is that there is no discrete 14th Amendment issue at stake in this case; the 14th Amendment is being cited as a way to activate the free speech issues.

And what did the Supreme Court rule? In the final paragraph, the court outlines that the law is unconstitutional, because it punishes “mere advocacy.” This, it suggests, is too broad. In the highlighted section on p.447, the Court argues that previous decisions have made clear that you can only bar advocacy of crime if it the speech is “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.”

Find the text of the First Amendment Here

Find the text of the Fourteenth Amendment Here

This is known as the Brandenburg test, and it still guides the law today. The idea is that if someone is advocating that a crime should be committed, then that should be protected speech unless the crime is likely to be committed right away. Only in that case is it appropriate to criminalize speech to prevent the crime from happening, to treat the speech as causing the crime in some direct sense. In all other cases, if a crime is committed, we hold the person committing the crime accountable. We give the speaker wide latitude to express their point of view to encourage full expression; and we trust that people are not easily persuaded to commit crimes. Rather than run the risk of repressing politically valuable speech, we trust in the deterrent power of the criminal laws. And we trust, too, that in the interim between the speech and the criminal act, there is plenty of time for individuals to reconsider and there is plenty of time for others to speak out against committing the crime.

Hypotheticals:

To illustrate this point, I use a little sequence of hypotheticals:

- If I hate a building on campus – I think it is named for someone whose politics I abhor; I find it aesthetically awful; I have some other extreme gripe – and I say it should be torn down, does that meet the standard?

- Students should see that it doesn’t, and for obvious reasons – it is not directed to inciting lawless action, that action is not imminent, and it is not likely to produce the action. And by calling for destruction in this more abstract way, I am expressing the strength of my political feelings about the building.

- What if I say someone should dynamite it overnight in a few months, over the school break?

- That is explicitly directed to a crime, but is neither imminent nor likely, and so doesn’t meet the standard.

- But what if there is a protest outside the building, I have a megaphone, and I tell the crowd to smash the building right now?

- Well, if the crowd is angry, and the crime looks likely to happen, and I am explicit that I want the crowd to break the law, I might have a problem. But as students should see, this is a very hard standard to prove, and so the Brandenburg test is very protective of free speech.

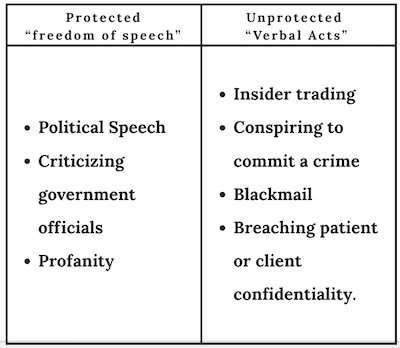

At this point, I normally need to clarify that this is about public advocacy for law-breaking. Conspiring to commit a crime is an entirely different matter – we don’t consider it a matter of free speech because it is done privately. There are no communicative benefits to the planning of the crime – there is no risk that we will chill public discussion or critique or the venting of anger – and so the same First Amendment issues do not arise. Conspiring to commit a crime is, of itself, a crime.

Final Context & Wrap Up:

The final question to explore is how did the court get to this conclusion? It reviewed a series of previous cases in which it had ruled on criminal advocacy cases, and distilled from them its test, which had not previously been stated so plainly. The cases are listed on 447-448, and two things are important to draw out. The first is that there was a case on the books from 1927 – Whitney v. California – in which the law in question was very similar to the Ohio law (they were passed around the same time). In that case, the Supreme Court ruled that it was constitutional to punish a woman – Anita Whitney – for joining an organization – the Communist Party – that advocated revolution. The decision was part of a long sequence of cases in which the Court had ruled that it was constitutional to criminalize Communist speech. This approach led to McCarthyism and the Second Red Scare. In the Dennis case in 1951, the Supreme Court ruled that it was constitutional to send 11 Communist Party leaders to jail for “conspiring to advocate” revolution – for teaching that revolution is an ultimate end-goal of the Communist movement (a decision that falls far short of the test established in Brandenburg!).

But, and this is the second piece of context to provide, over the late 1950s and early 1960s, as the fears of the McCarthy period cooled, the Court began to rethink these decisions, and to outline new tests that protected much more speech. These are the cases cited on 447-448, and which form the basis for the test newly elaborated in Brandenburg. And making that the standard required also overturning the Whitney decision from four decades earlier – an example of how the law evolves, and earlier precedent is overturned.

That explains the internal logic of the case. The remainder of class can be devoted to asking students to work through how they think about this decision. Normally, students find themselves quite uncomfortable with the fact that the Court has ruled in favor of a KKK member, and that it seemed to treat the case as the culmination of its tortured relationship with Communist speech rather than confronting directly the fact that this was a Klansman advocating racial violence.

The following two exercises can be useful for helping students work through these questions.

Classroom Exercise II: Thinking about free speech principles, not politics

Contents:

Overview

Context & Questions

Overview:

To help students grapple with the complexity of the Brandenburg case, I provide them with information about who his legal team was and what their motivations were for representing him. Included in this exercise is an interview with one of Brandenburg’s lawyers and a series of questions I find useful in prompting student discussion about this complicated topic.

Context & Questions:

Take students to the top of the case and ask them to identify the lawyers representing Brandenburg. The first lawyer named is Allen Brown – he was a Jewish lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). The other lawyers were also civil libertarians, including the fourth name: Eleanor Holmes Norton. Norton worked for the ACLU at the time, and later went on to serve for decades as Washington DC’s congressional representative. These were not, in other words, lawyers who shared Brandenburg’s politics. Here is a short clip of Norton explaining her role in the case:

Link to Video: C-SPAN- Supreme Court Landmark Case Brandenburg v. Ohio

I ask students what they think of Norton’s idea that she has a duty to defend the speech of speakers who would not defend her speech? There is no easy answer to this question, which will be deeply personal to individual students – the key is just to let students begin to work through their ideas about the importance of neutrality in speech rights.

I often pose some additional questions to prompt more discussion. Do students share Norton’s concerns about governments deciding which sorts of speech to prosecute? Do they share her faith that a “free for all” will produce a decent outcome? Do they share her faith that courts will apply neutral principles to protect all speech? Is it smart politics for liberals like the ACLU to defend groups that would not respect their rights? Or is it naïve?

Classroom Exercise III: What's the harm in hateful speech?

Contents:

Overview

Toleration Arguments

Restriction Arguments

Overview:

Students can be surprised to see that nowhere in the Court’s opinion does the court discuss Brandenburg’s speech as hateful or racist speech. As it seeks to assess whether Brandenburg’s speech might cause a harm that would justify punishment, the court focuses exclusively on the harm that the specific violence Brandenburg advocates – “revengeance” after the July 4 march – might actually come to pass. This is because of the Ohio law under which Brandenburg was charged (making it illegal to advocate crime) – and underlining this point can be a useful moment to discuss with students the Supreme Court’s role as an appeals court, limited to hearing the specifics of the cases that come before it.

But what if there had been a law barring Brandenburg’s speech because it was racist? Many other countries have hate speech laws, which criminalize speech because it is racist or derogatory. The U.S. does not; American free speech law protects the right to say even racist or hateful things.

The facts of Brandenburg offer an opportunity for students to think through how they feel about this controversial free speech question. As with Exercise II, the goal is not to lead students to a “correct” answer, but to help them understand some of the ways that the arguments have been made, and to begin to develop their own philosophies of free speech.

Toleration Arguments:

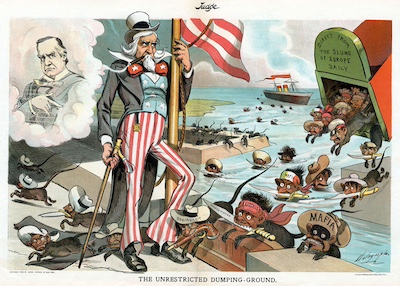

The arguments for tolerating even hateful speech flow from Eleanor Holmes Norton’s perspective on free speech that we looked at in Exercise II; they also flow from the idea of a “marketplace of ideas” that was established in the 1919 Abrams v. United States case, which is dealt with in the Free Speech Teaching Guide 1 In short, they are that that any standards that could be established will be vague and open to abuse, that there is much risk in allowing governments to pick and choose which speech to censor, and that there are benefits to society for allowing the airing out of controversial ideas – where they can be critiqued, rebutted, and, where necessary, debated – rather than driving them underground, where they may gain the mystique of “secret knowledge.”

The arguments against tolerating such speech require identifying harms that would be sufficient to justify censorship. In Brandenburg, the Court measured the likelihood that Brandenburg’s speech would cause the sort of mob violence on July 4 that he called for; the court found that such an outcome was not sufficiently imminent, likely, and explicit to punish the speech. But that is not the only harm one could imagine wanting to regulate.

Next, I provide two important examples of such arguments for restricting racist speech to avoid different types of harm.

Restriction Arguments:

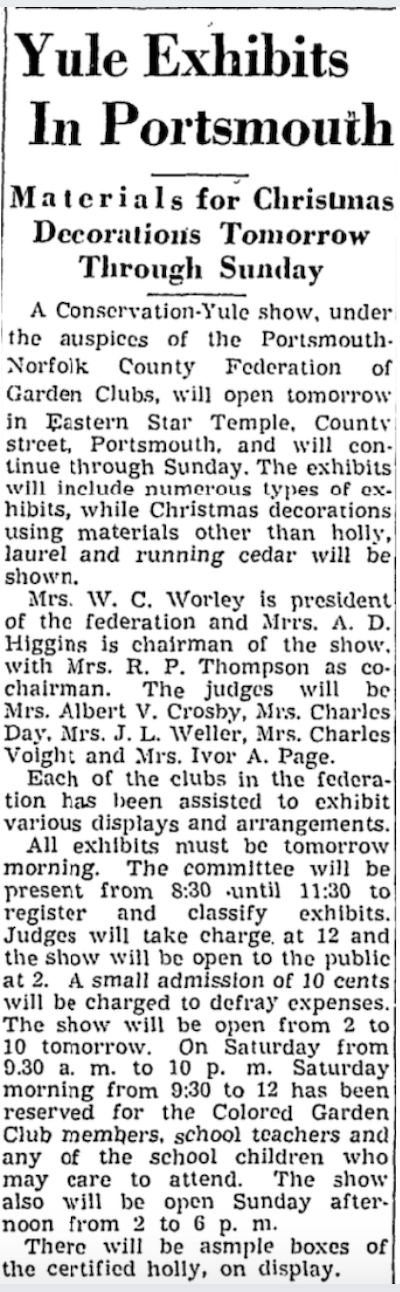

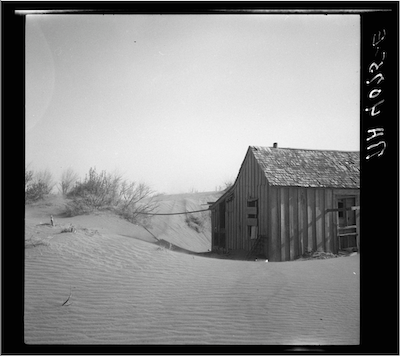

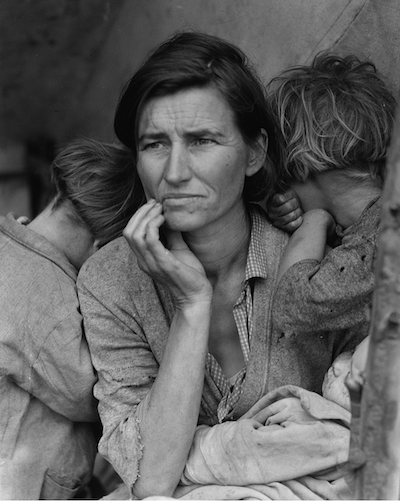

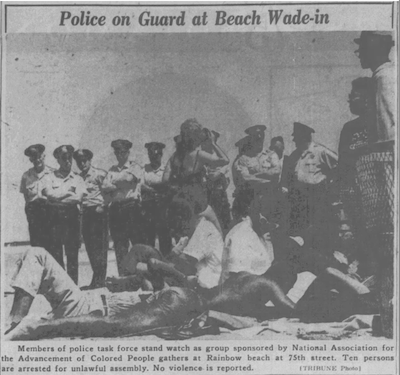

An argument could be made that racist speech can lead to crimes in a more general sense, by heightening racial animosity, and degrading the status of some members of the community so much that they seem legitimate targets for violence. Brandenburg was decided in 1969, but the case began with Brandenburg’s speech 1964 at a time when the conflict over civil rights was causing very real political violence: in the September before Brandenburg’s speech, for instance, a splinter group of the Ku Klux Klan bombed the 16th Street church in Alabama, killing four Black girls. One obviously cannot hold Brandenburg himself accountable for these crimes – they happened before his speech – but do students think that censoring hateful, violent speech like his would make such crimes less likely? And what about the risks of such censorship? And is it sufficient that bombing is outlawed?

The second argument, as made by philosopher Jeremy Waldron, argues that the harm of hate speech is not that it will lead to crime, but that hateful speech is, of itself, an attack on the dignity of particular groups of people and denies them of full inclusion in the political community. Whether or not this sort of speech leads to a crime, Waldron suggests, this is itself harmful enough to justify censorship. After all, it is illegal to defame individual people under U.S. law – though in the case of individual libel charges there are complex rules intended to balance this principle with the First Amendment; and any similar group defamation law would need to be similarly complex. But one can ask students whether the sorts of statements Brandenburg made in the footnote on p.446 are sufficiently harmful to the respect and status of members of the community that they fall outside the protections of the First Amendment.

In Brandenburg, the court did not consider these issues. But thinking about the case in these contexts helps students better understand the stakes of the free speech questions involved and also helps them think about how the court identifies the harms it analyzes in its decisions.

Appendix

Available in the PDF version of this guide, downloadable on the left of this page.