What is it?

Higher education in the United States has been shaped by history and has played a role in shaping history. Around the time of the American Revolution, college was almost exclusively for white men and, even then, often only for wealthy white men. Over time, women, Black Americans, the middle class, working class and poor Americans gained access to higher education, but this was not a simple story of gradual and steady reform. Instead new types of schools with new missions were founded at various points in the past, some were successful and some were not. Some still exist today, and all have changed over time emphasizing different courses of study and catering to new groups of students. This guide explores different types of schools and how they’ve developed over time.

Key points:

- This activity will take one 90-minute period or two 45-minute periods. It is appropriate for a high school U.S. history or government classroom, but can be modified for a variety of learners.

- Students will analyze, interpret, and evaluate primary sources.

- Students will learn more about the variety of colleges and universities in the United States and how they’ve changed over time.

- Guiding Question: What forms does higher education take in the United States?

Introduction

Charles Dorn has summarized the history of higher education in the U.S: “what we conveniently call ‘higher education’ today is in actuality a composite of institutional types that developed over the course of 200 years”. The different types of institutions include public institutions, both large and small, private colleges, some religiously affiliated, some not, Historically Black Colleges and Universities, women’s colleges, and community colleges - among others. While depictions in popular culture and even in news media outlets often focus on very elite universities, the vast majority of students do not attend these elite schools and are instead enrolled at the variety of institutions discussed above. The goal of this guide is for students to learn more about higher education today by looking at its history and specifically at the different types of institutions, why they were founded, and how that history shapes the present status of higher education.

Hook/Bellringer

At the beginning of class ask students to name colleges or universities that they have heard of and to add where did they hear about them. Write answers on the board or have students write the answers on the board. You can stop adding names after you have about 10 schools. Alternatively students could answer through a web platform like Padlet which could be projected on the screen.

Once there is a collection of schools on the board ask students: What do you know about these schools (ie are they public or private, 4 year or 2 year, larger or smaller etc.)

Introduce the activity by noting that there are a wide variety of institutions in higher education each with a different history. They were established for different reasons to meet different needs and they have changed over time to respond to changing student populations and to the world around them. Using primary sources — photographs of various schools — students will virtually “tour” different campuses to better understand these schools. Divide students into 6 groups based on institution type: Community Colleges and Junior Colleges, Large Public Universities, Regional Public Universities, Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Private Liberal Arts Colleges and Universities, and Women’s Colleges. When they’re in their groups provide the sources and the brief description of their type of school. Direct them to use the sources the virtually “tour” these schools. Ask them to take notes on what they notice:

What kind of facilities and buildings do you see?

What can you tell about the kinds of academic programs at these schools?

What kinds of activities are offered? (IE Sports? Recreation opportunities? Socializing opportunities? Museums?)

Do you think this is a state school or a private school? What makes you think so?

What other questions come to mind?

Digital Research Activity

Students will then choose a specific school to research historical sources. Using the historical newspaper database Chronicling America to find where the school is mentioned. They will create an informal “Then and Now” presentation based on similarities and differences they notice about the school in the past and in the present.

Tips for searching Chronicling America

- Look up the school on Wikipedia to see if it had a different name in the past. Use an older name as a search term on Chronicling America.

- Many colleges and universities advertised in newspapers so searching for the name of the school plus “courses” can be helpful for finding these.

- Search results can be filtered by state — this can be a way to narrow down the search results when searching for a specific school.

Primary Sources

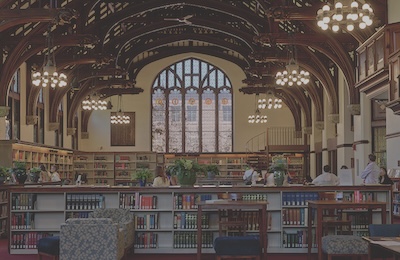

Women’s Colleges

Women’s colleges are typically private liberal arts colleges founded to provide women with a 4 year college education when opportunities for women in higher education were limited. Many women’s colleges were founded between 1870 and 1890. The number of women’s colleges in the United States grew until the mid-1960s when there were over 250 in the United States. Since that time the number of women’s colleges has decreased with the schools either closing, becoming co-ed, or merging with a men's college. As of 2024, there were 26 women’s colleges in the United States that fulfill a unique role educating and empowering women.

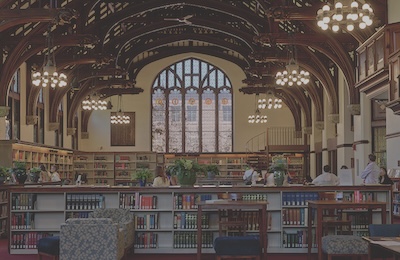

Mount Holyoke College

Inside the Emily Williston Library on the campus of Mount Holyoke College, a private women's liberal arts college in South Hadley, Massachusetts | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2019690140/

View of the campus at Mount Holyoke College, a private women's liberal arts college in South Hadley, Massachusetts | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2019690144/

View of the campus at Mount Holyoke College, a private women's liberal arts college in South Hadley, Massachusetts | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2019690145/

Smith College

Scene at the boathouse on the campus of Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, one of the "Seven Sisters" schools, an alliance of East Coast liberal-arts colleges created to provide women with education equivalent to that provided in the men-only Ivy League | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2019690193/

Scene at the botanic garden on the campus of Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, one of the "Seven Sisters" schools, an alliance of East Coast liberal-arts colleges created to provide women with education equivalent to that provided in the men-only Ivy League | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2019690192/

Pond and conservatory on the campus of Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, one of the "Seven Sisters" schools, an alliance of East Coast liberal-arts colleges created to provide women with education equivalent to that provided in the then men-only Ivy League | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2019690187/

Elmira College (founded as women’s college, now co-educational)

Gillett Memorial Hall, completed in 1891 on the campus of Elmira College in Elmira, New York | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2018700052/

Entrance arch on the campus of Elmira College in Elmira, New York | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2018700071/

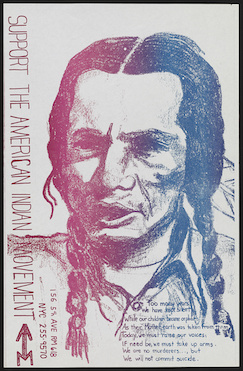

HBCUs

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) include both private and public schools that were established before the 1964 Civil Rights Act with the mission of providing higher education to Black Americans. There are 101 HBCUs in the United States that carry out the mission of educating Americans regardless of race and preserve Black American culture and history.

Grambling State University

A massive, horizontal "G" sculpture on the campus of Grambling State University, a pre-eminent HBCU (historically black college or university) in rural Grambling, Louisiana | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020744158/

The McCall Dining Center on the campus of Grambling State University, a pre-eminent HBCU (historically black college or university) in rural Grambling, Louisiana | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020744159/

The Frederick C. Hobdy Assembly Center on the campus of Grambling State University, a pre-eminent HBCU (historically black college or university) in rural Grambling, Louisiana | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020744160/

The home team's cheering section overlooking the 50-yard line at Eddie Robinson Stadium, the home field of the Grambling Tigers football team at Grambling State University, one of America's pre-eminent "HBCU" (historically black colleges and universities) | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020744093/

University of Arkansas Pine Bluff

Identifying sign and sculpture at the University of Arkansas Pine Bluff in Pine Bluff, Arkansas | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020741546/

The Walker Center multipurpose research hall at the University of Arkansas Pine Bluff in Pine Bluff, Arkansas | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020741547/

The Dawson-Hicks Hall dormitory at the University of Arkansas Pine Bluff in Pine Bluff, Arkansas | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020741567/

A clock that is the centerpiece of the University of Arkansas Pine Bluff in Pine Bluff, Arkansas | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020741724/

Lion sculpture on the campus of the University of Arkansas Pine Bluff in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, whose athletic teams are the Golden Lions | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020741566/

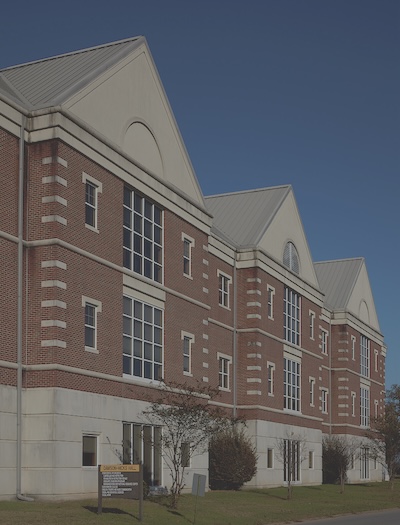

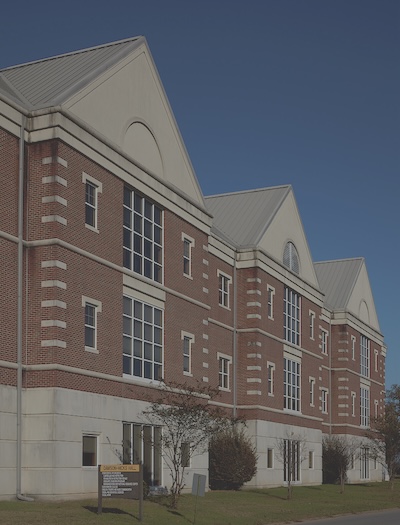

Regional Public

Regional public universities educate a large number of students in higher education. Many were founded as Normal Schools or Teachers Colleges and they continue to provide education to students in all areas of the country who may not have access to larger schools or private schools. According to the American Association of State Colleges and Universities these schools enroll a disproportionately higher number of students of color, of low-income backgrounds, first generation, Pell Grant recipients, community college transfers, working adults, and veterans compared with other public and private institutions.

Southern Oregon University

A springtime view of an academic building at Southern Oregon University in Ashland | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2018698087/

A cyclist passes before the library building at Southern Oregon University in Ashland | Library of Congress | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2018698081/

Stone artwork array on the grounds of Southern Oregon University in Ashland | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2018698083/

Metal-art sculpture on the grounds of Southern Oregon University in Ashland | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2018698082/

University of Texas-El Paso

Building on the campus of the University of Texas-El Paso | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2014631177/

Building on the campus of the University of Texas-El Paso | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2014631178/

Building on the campus of the University of Texas-El Paso | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2014631182/

The Chihuahuan Desert Garden and campus buildings of the University of Texas at El Paso | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2014630702/

Glass wall and stairway at the University of Texas at El Paso | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2014632620/

Glass wall at the University of Texas at El Paso | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2014632619/

Gateway sign at the University of Texas at El Paso | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2014632616/

The University of Texas at El Paso | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2014632618/

West Chester University

This is a ram statue, though not a golden one, in front of the Old Library building on the campus of West Chester University in West Chester, Pennsylvania. The school's sports teams are nicknamed the Golden Rams. The Department of Anthropology and Sociology, and the Institute for International Development are housed in the 1902-vintage building | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2019689476/

This is a ram statue, though not a golden one, in front of the Old Library building on the campus of West Chester University in West Chester, Pennsylvania. The school's sports teams are nicknamed the Golden Rams. The Department of Anthropology and Sociology, and the Institute for International Development are housed in the 1902-vintage building | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2019689477/

The Old Library building on the campus of West Chester University in West Chester, Pennsylvania. The Department of Anthropology and Sociology, and the Institute for International Development are now housed in the 1902-vintage building | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2019689478/

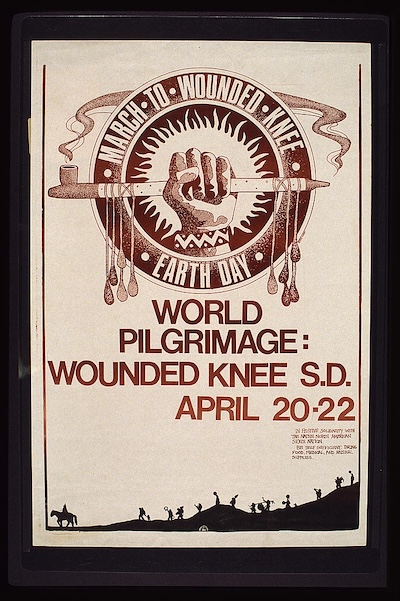

Large Public

Large public universities enroll tens of thousands of students. Many started as Land Grant Schools, a federal program that began in 1862 with the Morrill Act and the Second Morrill Act of 1890. Funds were raised by selling western lands, most of which had been taken from Native Americans, sometimes even without a formal treaty. (see Landgrabu.org for more). Land grant schools were established to promote applied science in agriculture and industry but now most large public universities offer a wide range of degrees in including liberal arts. Many of these institutions also have a strong research focus.

University of Michigan

University of Michigan Campus, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Aerial view | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020714690/

University of Michigan Campus, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Tower | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020714700/

Power Center for the Performing Arts, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Exterior | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020714689/

Angell Hall, an academic building at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. It is after James Burrill Angell, who was the university's president from 1871 to 1909. The Angell Hall Observatory is located on the fifth floor roof of the building, which opened in 1924. On March 24, 1965, Angell Hall was the site of the first "teach-in" protesting the Vietnam War. More than 3,000 people attended the all-night program of seminars, rallies and speeches | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020722994/

The 1936 Burton Memorial Tower on the campus of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Named for former university president Marion Leroy Burton, the carillon tower, designed by Albert Kahn, now (as of 2019) houses the Baird Carillon, classrooms, and faculty offices for members of the Department of Musicology | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020722990/

The University of Michigan Art Museum, in the 1910 Alumni Memorial Hall on the campus in Ann Arbor. Its original purpose was threefold: to provide a space for the university's growing art collection, open space for the graduate school, and honor alumni who had served in the nation's wars to that date | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020722995/

Abstract impressionist artist Mark di Suero's 53-foot-high "Orian" sculpture enlivens the campus of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Initially exhibited at Chicago's Millennium Park, it arrived on campus on long-term loan in 2008. Ten years later t was removed because of drainage repairs, which provided an opportunity to send the sculpture back to the artist's studio in New York for conservation work and a fresh coat of vibrant reddish-orange paint | Library of Congress | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020722993/

University of Wyoming

The sports arena and auditorium at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, Wyoming | Library of Congress | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015632803/

S.H. Knight's Tyrannosaurus sculpture stands near the entrance to the Geological Museum at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, Wyoming | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015632813/

Cooper House, home to the American Studies program at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, Wyoming | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015632809/

D. Michael Thomas's "Breakin' Through" statue at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, Wyoming. The statue evokes the university's "Cowboys" sports nickname ("Cowgirls" in the case of women's teams), and the state nickname as The Cowboy State | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015632797/

The Marian H. Rochelle Gateway Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, Wyoming, a convocation center that the university calls its "front door" | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015632795/

Engineering Hall, home to the engineering department at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, Wyoming | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015632814/

The Arts and Sciences building at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, Wyoming | Library of Congress | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015632812/

The College of Agriculture building at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, Wyoming | Library of Congress | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015632811/

The College of Business building at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, Wyoming | Library of Congress | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015632810/

University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Louise Pound Hall on the University of Nebraska campus in Lincoln, the capital city of the midwest-U.S. state, houses (as of 2021) the Department office of Child, Youth and Family Studies and the office of the College of Education and Human Sciences | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2021758197/

Once the college engineering building, Richards Hall on the University of Nebraska campus in Lincoln, the capital city of the midwest-U.S. state, now (as of 2021) houses the School of Art and the Eisentrager-Howard Art Gallery | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2021758196/

Since 2003, the Van Brunt Visitors Center has served as the unofficial "front door" to the campus of the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, the capital city of the midwest-U.S. state | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2021758202/

Japanese artist Jun Kaneko's 2009 "Untitled" ceramic and galvanized-steel sculpture outside the Sheldon Museum of Art on the campus of the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, the capital city of the midwest-U.S. state | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2021758200/

Artist Ed Carpenter's "Harvest" sculpture greets those approaching the Pinnacle Bank Arena, the home of the University of Nebraska men's and women's basketball teams in Lincoln, the capital city of the midwest-U.S. state of Nebraska | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2021758193/

These four columns have become a landmark on the campus of the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, the capital city of the midwest-U.S. state | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2021758203/

The Sheldon Museum of Art, on the campus of the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, the capital city of the midwest-U.S. state | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2021758198/

Private, Liberal Arts

Liberal arts colleges offer 4 year degrees and also emphasize a broad education and general knowledge including science, history, literature, math, and languages. Private schools tend to be smaller and many, although not all, were originally founded as religious institutions.

Amherst College

The campus quadrangle, colloquially called the "quad," at Amherst College, a private liberal-arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts | Library of Congress

https://www.loc.gov/item/2019690237/

The Keefe Campus Center, the student activities building at Amherst College, a private liberal-arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2019690233/

The Keefe Campus Center, the student activities building at Amherst College, a private liberal-arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2019690234/

Davis & Elkins College

Campus view of Davis & Elkins College in Elkins, West Virginia. The Albert Hall science building is in the foreground | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015631689/

Campus view of Davis & Elkins College in Elkins, West Virginia. The Albert Hall science building is in the foreground | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015631691/

Graceland mansion on the campus of Davis & Elkins College in Elkins, West Virginia | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015631695/

Halliehurst mansion on the campus of Davis & Elkins College in Elkins, West Virginia | Library of Congress | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015631694/

Booth Library on the campus of Davis & Elkins College in Elkins, West Virginia | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015631692/

St. Olaf College

A woodsy fall view of a portion of the campus of St. Olaf College, a private, liberal-arts college in Northfield, Minnesota | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020723532/

A woodsy fall view of a portion of the campus of St. Olaf College, a private, liberal-arts college in Northfield, Minnesota | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020723535/

A woodsy fall view of a portion of the campus of St. Olaf College, a private, liberal-arts college in Northfield, Minnesota | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020723538/

A portion of Boe Memorial Chapel on the campus of St. Olaf College, a private, liberal-arts college in Northfield, Minnesota | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020723536/

A portion of Boe Memorial Chapel on the campus of St. Olaf College, a private, liberal-arts college in Northfield, Minnesota | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020723539/

Mellby Hall, the oldest residence hall on the campus of St. Olaf College, a private, liberal-arts college in Northfield, Minnesota | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020723530/

Mellby Hall, the oldest residence hall on the campus of St. Olaf College, a private, liberal-arts college in Northfield, Minnesota | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020723531/

Boe Memorial Chapel on the campus of St. Olaf College, a private, liberal-arts college in Northfield, Minnesota | Library of Congress

https://www.loc.gov/item/2020723537/

The Theater Building on the campus of St. Olaf College, a private, liberal-arts college in Northfield, Minnesota | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2020723533/

Community Colleges and Junior Colleges

According to the U.S. Department of Education, almost half of all students in higher education are enrolled in Community Colleges or Junior Colleges. Over half of adults with a 4 year degree began their education at a community college. Community colleges and junior colleges also enroll a high number of first generation students and lower income students. While the first institution of this type was established in 1901 with the founding of Joliet Junior College (JJC) in Joliet, Illinois, the largest growth of community colleges occurred after 1945 as college attendance rose overall the federal and state government encouraged the development of schools that could bridge the gap between high school and college, provide training in trades, and serve as cultural centers for communities.

Western Wyoming Community College

Buildings at Western Wyoming Community College in Rock Springs | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2017688034/

Buildings at Western Wyoming Community College in Rock Springs | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2017688035/

Buildings at Western Wyoming Community College in Rock Springs | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2017688036/

Potomac State College of West Virginia University

Davis Hall, a dormitory and conference center at Potomac State College of West Virginia University, a two-year junior college affiliated as a division of West Virginia University located in Keyser, West Virginia | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015631540/

Science Hall at Potomac State College of West Virginia University, a two-year junior college affiliated as a division of West Virginia University located in Keyser, West Virginia | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015631537/

Catamount statue at Potomac State College of West Virginia University, a two-year junior college affiliated as a division of West Virginia University located in Keyser, West Virginia | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015631534/

Academy Hall at Potomac State College of West Virginia University, a two-year junior college affiliated as a division of West Virginia University located in Keyser, West Virginia | Library of Congress | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015631538/

Reynolds Hall, a dormitory at Potomac State College of West Virginia University, a two-year junior college affiliated as a division of West Virginia University located in Keyser, West Virginia | Library of Congress | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015631539/

The 1919-vintage Administration Building at Potomac State College of West Virginia University, a two-year junior college affiliated as a division of West Virginia University located in Keyser, West Virginia | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015631542/

Mary F. Shipper Library at Potomac State College of West Virginia University, a two-year junior college affiliated as a division of West Virginia University located in Keyser, West Virginia | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015631535/

Potomac State College of West Virginia University, a two-year junior college affiliated as a division of West Virginia University located in Keyser, West Virginia | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015631536/

Overview of Potomac State College of West Virginia University, a two-year junior college affiliated as a division of West Virginia University located in Keyser, West Virginia | Library of Congress | www.loc.gov/item/2015631541/