In a world where kids are extremely familiar with a robotic "Turn left," and may have never actually seen a road atlas, geography has never been so important in the history classroom. Until mental maps, geography lessons did not often win the battle against history standards for precious time in my classroom. Now instead of being a sideshow, I consider maps a necessary step in teaching and checking for comprehension. Learning history content needs to be partnered with visualizing the environmental influences. After all, in order to understand how America was shaped, knowledge of the land is crucial.

Mental maps add another dimension to the history classroom. If you are not utilizing them to teach American history concepts, I recommend that you read below to discover how they help to build connections, incorporate different learning styles, and check for depth of understanding.

What is a Mental Map?

A mental map is a rough sketch of the world simplified enough that the outline can be remembered and repeated. The outline of the map can then be labeled with physical, political, or historic details.

How Do I Teach Mental Maps?

(The map described draws USA and its immediate neighbors.)

The Set-Up:

The teacher simply needs an overhead projector and some wet erase markers to begin (colors help!). The students need a piece of lined or computer paper and a writing utensil.

Before starting to draw, it is important to emphasize that no two mental maps will look identical.

First, I recommend figuring out a folding system that works for you. Folding the paper before beginning keeps the maps more proportionate. I like my students to divide the paper into six parts. Draw imaginary fold lines across the overhead to help orient the students.

Before starting to draw, it is important to emphasize that no two mental maps will look identical. Students can have trouble accepting that, and for the perfectionists this can be a particular challenge.

The Story:

The most important step to teaching mental maps is creating a story that will aid in memory. Tell the story using the overhead projector as a visual guide. After telling each part of the story, draw the corresponding piece of the map on the overhead, have the students repeat the steps, and periodically check their papers. Once they learn the outline, we use it throughout the year again and again so they have a very good understanding of our basic geography.

Many different stories could work and I have experimented with a few. This year, I told the story of "Norbert Americus, Zookeeper Extraordinaire." The story goes: Mr. Americus wanted to make the best zoo possible so he started collecting the biggest animals that he could. (If you prompt the students, you may find that they are very good at guessing the animals.) First he collected an elephant and a giraffe. Then he decided to get the very biggest animal even though he lives in the sea. Add a whale's tale to the top.

A little prairie dog wandered over from the deserts of America to see these big animals. He saw them and panicked. He took one look back and scurried all the way to the edge of the paper.

When the prairie dog arrived in Alaska, another nervous animal was there—a turtle. The turtle popped his head out when he saw the prairie dog.

The prairie dog and the turtle had each other now. They realized they had reached the West Coast so they decided it was time to chiiiiiiill out. Actually they chilled out so much that they were all the way down the Baja Peninsula before they knew it!

Just about then, the turtle and the prairie dog started talking. The animals in Mr. Americus's zoo seemed nice enough. In fact, none of those animals even eat turtles or prairie dogs. They turned back around and asked if they could be part of the zoo. The big animals liked the small animals and they of course said- "Y not?"

And that is the story of the Mr. Americus's Zoo!

In the first map that I teach, we draw the 2001 USA so we add an animal from way down low and way up high to the zoo—a snake and a bird—to outline the three major countries.

For American history, I do not include all of North America for simplicity's sake and I also exaggerate the size of America compared to Canada in order to fit features throughout the year. These two factors should be pointed out to the students, and you should show them a real map and discuss the purpose of a mental map versus a real map.

How Does This Apply to American History Specifically?

In world history, mental maps had been a great way to teach all of the different continents, so when I began U.S. history, I was concerned about the efficacy of repeating the USA map. I have discovered that not only can the single outline work, it is also beneficial to establish that one outline early on and recycle it so the focus can move to the details. Also, this helps to connect the historic pieces. For example, adding the Treaty of Paris land, then the Louisiana Purchase, and then the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the students can really visualize the growth of our nation.

As you view the maps, please note that they also help orient the students to their country. Many of my DC students have never made it to see the White House, let alone making it past Maryland or Virginia. So they can establish the basic size and geography of our country in relation to places that they have heard of or seen on television.

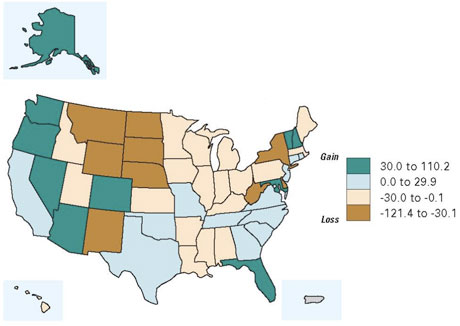

Some of the maps I have used include:

Top 5 Reasons I Recommend Mental Maps

- Mental maps are accessible. The students have fun as if they have learned a neat new trick, and yet pretty soon they can easily locate the land America gained in the Treaty of Paris or describe the length of the Trail of Tears.

- Mental maps provide an avenue for students with different talents to shine on an actual test. Often times these talents show up in projects or classwork, but this aids that talent to come out in more rigid assessments as well.

- Mental maps force some traditionally excellent students to stretch their brains and skills outside of their comfort zone.

- Mental maps are simple to modify. I provide a few special education students the basic map outline and allow them to fill in the details important to the unit.

- Mental maps allow the teacher to check the difference between test memorization and actually comprehending the material. If they are able to answer that the Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the United States on a multiple-choice question but then make that land a mere sliver on the map, the teacher knows that they have reached a level of regurgitation rather than of actual learning.