We work with a Teaching American History Grant called Becoming Historians. It's working with elementary school kids, and one of the units of study in the New York City curriculum for 5th grade is this idea of westward expansion, and we came up with this—we realized that we had a bit of a stumbling block because when you're talking westward expansion, it's a pretty traditional model and teachers are doing Oregon Trail. And our kids who live in New York City have no conceptual knowledge of what a plain is or a mountain or a mountain pass. They have very little understanding, even, of what happens upriver. So while we were getting ready to do this work around westward expansion and what's out there, we wanted to help the kids make pictures in their minds to really have good empathy and historical imagination of what's going on. We realized we needed to do some foundational work on mapping.

. . . when you're talking westward expansion, it's a pretty traditional model and teachers are doing Oregon Trail. And our kids who live in New York City have no conceptual knowledge of what a plain is or a mountain or a mountain pass.

So I contacted an elementary-school/middle-school teacher at Bank Street College of Education, Sam Brian, who's done a lot of work on geography teaching and young children. And he does this terrain model map and it's a generic model with mountains and valleys and you flood it and you can see how islands are formed from mountains that are connected to the land, but then they become submerged. So the kids can see all this stuff actually happening.

So they're getting that kind of general vocabulary, but then they're also getting specific vocabulary about mountains and peaks and passes and ranges and river valleys and estuaries and all that other kind of language that our children need.

So we had Sam work with us on the terrain models, and then the idea is you go from the terrain model to a map that the children draw, a two-dimensional map the children draw, of the terrain model.

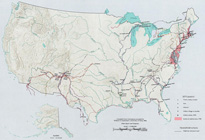

They look at maps of the actual physical world and they trace river routes and they figure out where the Continental Divide is, because you have rivers draining into one ocean or the other, and so there must be something high up in between that's causing the water to flow downhill. So: "Aha! Those must be mountains." So then you draw in the mountains and then you label all the places. So there's a lot of really rich background work that takes place.

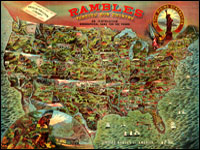

And from that point we went into maps of the Oregon Trail, historic maps from 1843 that we found on the Library of Congress website. And so the kids are doing critical map reading because now they have the knowledge to say, “Oh, it's a pass. It's a butte. It's a bluff.” They're reading those labels on the map and it means something to them because they've seen pictures of it and a three-dimensional model of it. Because it's hard for us in the city to take our kids to places that represent these things.

They're reading those labels on the map and it means something to them because they've seen pictures of it and a three-dimensional model of it.

So then we looked at the Oregon Trail maps and talked about those maps and used the NARA forms to analyze the map: Who is the author? What was the purpose? What was happening at the time? And then we took diaries of peoples' westward journeys and traced those journeys along the maps so the kids could start making the connection between, "Oh, on June first, July second, we passed Independence Rock." And on, "We went through Devil's Gate." And all those places are labeled on the maps, so the kids are then tracing the progression of the individual who wrote the diary along the map and trying to get in their head what it's all about.

Rethinking the Oregon Trail

Terri: We had a plan for the content, but it was kind of vague. And then coming out of conversations with teachers and making observations in classrooms and figuring out what resources we could pull together, we—like, my original idea for westward expansion was not to do the Oregon Trail, it was to crack it open and do stuff about black pioneers and Exodusters and stuff, but all the teachers are doing this Oregon Trail thing. So I decided to, like, put my desires aside, and then focus on the Oregon Trail thing to think about: How can we make this a more rich experience? How can we enhance what they're already doing in the classroom, so that they're not, like, tossing the baby out with the bathwater? To start with something totally new, or just going to my workshop and learning about the Exodusters and then filing it away and continuing on with their Oregon Trail stuff.

I mean, that's what—the resources in their classroom are largely Oregon Trail, which is why it's taught. So we use that to retool it and then we brought in this idea of mapping and that came from talking with teachers about what their kids needed and me trying to think about what resources I knew were in the city and how could we make this more engaging, more interesting.

Preventing Learning Fragmentation

We're really working on mapping the curriculum to see how it spirals up, so that you're introducing this idea of a grid maybe in 3rd or 4th grade, and then in 5th grade you're starting to introduce the ideas of latitude and longitude. When you're looking at the Oregon Trail maps, the grid becomes not "A, B, C, 1, 2, 3," it's "degrees north and south" that the kids are actually using to orient themselves on the map.

So it's a way of, you know—they understand the idea of grid, and then they go into the more complicated thing of latitude and longitude. And then we're trying to think about—break it apart. What's on the maps, the historic maps that they're actually using, and then how do we scaffold that so that it aligns with the history curriculum and the geography curriculum so that the kids are not doing the geography unit and then it's, like, done with that, knock that one off the list, let's go to history now.

. . . the kids are not doing the geography unit and then it's, like, done with that, knock that one off the list, let's go to history now.

'Cause Sam's been doing this work since the early mid-90s, I think, and he says that that's the one thing that he's consistently struggling with teachers to get them to do is to make that transition between the work that you do with the terrain models and the imaginary land maps, and then taking it back into social studies and having the teachers actually use it and have the kids apply the information and the ideas that they've gotten from the first part of the work. And so that's really what we're trying to make a little bit more obvious and to make it more articulate.

Michele: To give the teachers the knowledge, the actual content knowledge, to reinforce that because it's not just their field. You know, you have to really study up on it and know what you're teaching and know it in depth so that you actually understand yourself what you're teaching the kids and not be afraid to go a little bit further. We know how to do this very well in the language arts, because that's what New York City has been really focusing on, and understandably. But now it's time to put that focus into history, into geography, and to integrate it.

Terri: The Wildlife Conservation Society has a very cool project happening using historic maps to determine what New York City, Manhattan in particular, looked like in 1609 when Henry Hudson sailed up for the first time.

So Sam came and did the same work with the 4th-grade teachers. Instead of focusing on interior landforms, they focused on coastal landforms. So they thought about peninsulas and coves and bays and the river systems, so that that's all very immediately transferred to New York City and New York State geography, and it leads the kids very nicely into 5th grade. And then they did—they looked at historic maps of early colonial New Amsterdam and New York.

Bringing History Home

Michele: Kids are working in partnerships, we put transparencies over the flat version and then we actually go over where the rivers were, where the bluffs were, where the canyons are, where the coast is, so that they get a three-dimensional view on this flat map of what it was like before the skyscrapers, and also where our school is, where their houses are in relation to this. And then we look at it next to Manhattan now. Like: what’s happening now, what happened then.

Terri: Right. And since you did it on transparency, you can take this—

Michele: Right.

Terri: And lay it on top, and you can see how the shape of Manhattan has changed over time. 'Cause you can see that all the hills that were down on the Lower East Side are flattened and the marshes are filled in and the coastline has changed and the rivers are paved over, and you can see all that stuff on the map.

Michele: Along with the mapping, the idea of taking them on trips that reinforce what they're learning two-dimensionally.

Terri:: There's a living museum along the Hudson River called Philipsburg Manor, and it interprets colonial New York history from an enslaved person's perspective. So we thought of, like, taking the train up along the Hudson. You get to see the width of the Hudson. You see the Palisades on the New Jersey side. You can see that there are hills on the New York side, so that there's stuff you can see to, like, "Oh, right. That's a river. And there's a really long bridge going over that river. A couple of them."

Michelle: And also even when we got there, there are, like, sort of culverts where you see that the—go underneath the sidewalks. I mean, you can actually tell that there was water under there, you know? And when you look at these huge expanses of land, except for Central Park, we don't really have huge expanses of land. So—

Terri: Right. And all our rivers are—all of the rivers that are on these British headquarter maps are all gone.

I think that when you do tie together these 3D models and you actually have them make their own maps and you have them take the trips and then tie in the history that goes with it, it gives a much better experience than just trying to read a standard text. . .

Michele: I think that when you do tie together these 3D models and you actually have them make their own maps and you have them take the trips and then tie in the history that goes with it, it gives a much better experience than just trying to read a standard text, which really is what people failed with. And because of this previous failure, I think teachers shied away. And now we're really giving alternatives to text, which are much better.