Questioning History Using the Census

What can we learn about the importance of population change and industrial development in Detroit, MI? What does the Detroit story tell us about industrialization in American history? Do upsurges or downturns in the population become permanent? Or do they change direction again? Where do the people come from who determine the population changes, and where do they go? The 2010 Census and other demographic data helped me answer these questions for myself. Students can use demographic data to answer questions in similar ways.

Detroit's volatile population changes drew media attention in the spring of 2011 as the 2010 Census figures were being rolled out. I became curious about the reasons for this population change. The overall U.S. population reached 308 million in 2010, about a 10% growth rate, from 2000. Most states and major urban areas grew at a 1% per year rate. There were, however, a few areas which did not grow, but declined. One of those was Detroit.

I wanted to know more about the situation with Detroit and why people came and left at different times in its history. I looked into Detroit's population history through the once-a-decade census reports that are available from the U.S. Census Bureau, the 2010 Census website, and the University of Virginia's Historical Census Browser. The Census Bureau also published the American Community Survey in the years 2005–2009 that covers occupations, social statistics, housing, mobility, language use, country of origin, and other data. These surveys are available on Detroit's Population and Housing Narrative Profile and in its American FactFinder.

To get a feel for the demographic volatility in the history of Detroit since 1850, I examined the Census figures for each year and the percentages of increase or decrease:

Now that I had the numbers, I looked for interpretations. An NBC analysis of Census figures attributes the Detroit population decline to "steady downsizing of the auto industry":

Detroit's population peaked at 1.8 million in 1950, when it ranked fifth nationally. But the new numbers reflect a steady downsizing of the auto industry—the city's economic lifeblood for a century—and an exodus of many residents to the suburbs. Detroit's population plunged 25% in the past decade to 713,777, the lowest count since 1910, four years before Henry Ford offered $5 a day to autoworkers, sparking a boom that quadrupled the Motor City's size in the first half of the 20th century.

This led me to ask, what did Detroit's actual population look like in earlier years? I examined some of these periods of time, using older census data. The 1950 U.S. Census found that the population of the city was 1,849,568. It had grown by over 200,000 from its 1940 population of 1,623,452. The foreign-born population was 276,000 from Canada, Poland, Italy, Germany, the USSR, England/Wales, and Scotland. The black population was 300,506. The 1910 U.S. Census revealed that the total population was 465,786. The native white population was 115,106, the black population was 85,000, and the foreign born was 156,555. The foreign born of this era came from Germany, Canada, Russia, Austria, Hungary, Ireland, and Poland.

Finally, I checked Detroit's pre-industrial censuses from 1850 to 1880 and found the area to be rural but commercially active as a Great Lakes port. It grew rapidly in these years, but had only a small fraction of the population it would later have during the rapid growth of the auto industry.

Now I had another question. Where did the people who contributed to this growth come from? The Detroit News' website, detnews.com, gave me an answer in an article by Vivian Baulch entitled "Michigan's Greatest Treasure-its people." This article presents an ethnic description of Detroit from the time that it was an important stop on the Underground Railroad through the boom years of the auto industry. The article concludes with a quote by historian Arthur Woodford:

Detroit has "the largest multi-ethnic population of any city in the United States. Detroit has the largest Arabic-speaking population outside of the Middle East, the second largest Polish population in America (only Chicago has more), and the largest U.S. concentration of Belgians, Chaldeans and Maltese."

Another source is the U.S. Senate's hearings in 1908–1911 on Immigration and Industry. Known as the Dillingham Commission, the hearings' 31 volumes have been digitized by Stanford University's e-brary. Volume 8 provides an insight into Detroit's diversity as shown by the children of immigrant workers in their school settings.

These population figures, when I connected them to the rapid growth and consolidation of the auto industry and the upsurge in immigration and internal migration, gave me an overview of what happened in Detroit. It showed a boom and bust cycle in industry and the apparent willingness of many people to leave the city and/or metropolitan area when economic conditions are bad. The rise and decline of the American auto industry helped me get a grip on industrialization as a major factor in population growth and decline. Other industries such as iron, steel, car parts, batteries, tires, and glass are at least partially dependent on, or tied to, the fortunes of the auto industry, and thus whatever happens to the auto industry in Detroit has an impact on the national industrial scene. Other nearby formerly industrial cities have demographics similar to Detroit's. However, the decline may not be permanent. The auto industry has begun a modest revival and may continue to grow in the near future. Detroit is still the center of this industry and may again rise to a greater position of prominence among American cities.

By exploring census and other demographic data, students can form their own historical questions and answer them by tracing quantitative and interpretative information, just as I did. Population and industry shifts can rarely be understood from one source. Ask a question and use the information you find to assemble you own answer.

Associated Press. "Census: Detroit's population plummets 25 percent". March 22, 2011. Accessed May 26, 2011.

Baulch, Vivian. "Michigan's Greatest Treasure-its people." Detroit News. September 4, 1999. Accessed May 26, 2011.

Intimidated by the thought of working with quantitative data (numbers)? Professor Gary Kornblith guides you through finding and interpreting such data.

If you're looking for some numbers to crunch, more than 50 websites we've reviewed feature quantitative data. Last year, our blog also suggested ideas for teaching with census data.

Of course, they realize very quickly that the only way to do this is to use sign language—so many fingers for the month and then the day once they have found others born in the same month. After a few minutes of positioning and repositioning, from the first in line to the last, students announce their birthdays.

Of course, they realize very quickly that the only way to do this is to use sign language—so many fingers for the month and then the day once they have found others born in the same month. After a few minutes of positioning and repositioning, from the first in line to the last, students announce their birthdays.  From that point, students are formed into groups of four and we talk briefly about the class. I start by asking them about their attitudes toward history and then give them my three guarantees. Regarding their attitudes I always seem to find that roughly a quarter of my students like history, another quarter dislike history, and the rest are ambivalent. It is then time for my three guarantees:

From that point, students are formed into groups of four and we talk briefly about the class. I start by asking them about their attitudes toward history and then give them my three guarantees. Regarding their attitudes I always seem to find that roughly a quarter of my students like history, another quarter dislike history, and the rest are ambivalent. It is then time for my three guarantees: When the short tale is complete you say to your students: what you must figure out is why John’s family would leave their beautiful farm for a difficult life in this flat dry prairie.

When the short tale is complete you say to your students: what you must figure out is why John’s family would leave their beautiful farm for a difficult life in this flat dry prairie.

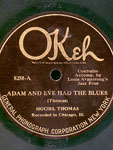

I am heartened when I communicate with prospective history educators who believe in the idea of teaching history beyond the textbook. These future teachers share innovative ideas of image and document analysis in an effort to move students toward developing historical habits of mind and keen interest in the world around them. It is my contention that teachers can and should consider the use of music in the same way they consider more archetypal sources—as essential to effective teaching.

I am heartened when I communicate with prospective history educators who believe in the idea of teaching history beyond the textbook. These future teachers share innovative ideas of image and document analysis in an effort to move students toward developing historical habits of mind and keen interest in the world around them. It is my contention that teachers can and should consider the use of music in the same way they consider more archetypal sources—as essential to effective teaching.