Writing Critiques of Primary and Secondary Sources

I have been asked to critique my primary and secondary sources at the end of

my paper. What should these critiques focus on and how long should they be?

Including the sources you consulted for a history paper is important. Your bibliography helps readers see what sources you used to make your claims and your argument. When each of the accounts is accompanied by commentary, we call that an annotated bibliography. This sounds similar to what your teacher wants for this assignment.

But before including some general guidelines for writing this addendum, let me suggest that you directly ask your teacher this question. This is the best way to find out your teacher's specific expectations. (It’s likely that some of your fellow students would also benefit from hearing those—usually when one student is confused, others are also.)

Having said that, here are some general guidelines:

- Keep each critique short. A few sentences are often sufficient and it should be no more than a paragraph.

- “Critique” in this case does not mean that you have to be negative about the source. Rather it means that you need to analyze and question each source.

- Use your own argument to help you choose how and where to focus your critique. Some questions that can help include:

- How did each source help you construct your argument and inform your synthesis of the sources? What sources stopped you in your tracks and made you reconsider how you were thinking? What sources reinforced your ideas?

- Did a source offer a new perspective or contradictory information? Which sources helped you with background knowledge or pointed you towards other useful sources to consult? How did this source’s content or perspective compare with other sources you consulted?

All of these questions can help you assess a source’s value for understanding your historical topic—the ultimate purpose of your critique.

Remember that when using a source from the time under study, you need to not only understand its content, you need to analyze that content. Ask questions of the source like: Who wrote it? When was it written? What was going on at that time? Who was the audience? What was the author’s purpose? Does the author use loaded words? Whose interests are represented by this source? These kinds of questions not only help you understand the source more deeply and accurately, they also help you critique it.

Similarly, you need to ask questions about any secondary source that you use. Start with asking: What is the author’s argument? What evidence does s/he use to make that argument? Does the evidence support the author’s argument? Also ask: Does the author consider alternative explanations and arguments? How does the account compare with other sources that you have consulted? Who is the author and does s/he have credentials or experience that make them trustworthy?

I am not suggesting that all of these questions should be answered in your critique, and indeed, given the brevity of each critique, that would be impossible. Rather they are examples of ways to assess the value of each source to your argument and the topic under study.

Finally, remember that if you judge a source “great,” “terrible” or with some other descriptor, include a specific statement about why it was great or terrible. For example, you might say something like, “This book was incredibly helpful” and then add the specific, “as it laid out the varied ways that historians have interpreted the conditions under slavery over the past 60 years.”

Good Luck!

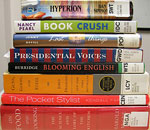

Mary Lynn Rampolla, A Pocket Guide to Writing in History, Fourth edition, (Boston: Bedford St. Martin’s, 2004).