American Resistance to a Standing Army

Quote from Madison: "The means of defence against foreign danger, have been always the instruments of tyranny at home. Among the Romans it was a standing maxim to excite a war, whenever a revolt was apprehended. Throughout all Europe, the armies kept up under the pretext of defending, have enslaved the people."

I understand what he means, but can you give some specific examples of which events Madison was talking about. Can you give other ancient examples where foreign wars are used as a type of diversion?

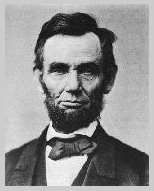

In June of 1787, James Madison addressed the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia on the dangers of a permanent army. “A standing military force, with an overgrown Executive will not long be safe companions to liberty,” he argued. “The means of defense against foreign danger, have been always the instruments of tyranny at home. Among the Romans it was a standing maxim to excite a war, whenever a revolt was apprehended. Throughout all Europe, the armies kept up under the pretext of defending, have enslaved the people.” That Madison, one of the most vocal proponents of a strong centralized government—an author of the Federalist papers and the architect of the Constitution—could evince such strongly negative feelings against a standing army highlights the substantial differences in thinking about national security in America between the 18th century and the 21st.

While polls today generally indicate that Americans think of the military in glowing terms (rightly associating terms like “sacrifice,” “honor,” “valor,” and “bravery” with military service), Americans of the 18th century took a much dimmer view of the institution of a professional army. A near-universal assumption of the founding generation was the danger posed by a standing military force. Far from being composed of honorable citizens dutifully serving the interests of the nation, armies were held to be “nurseries of vice,” “dangerous,” and “the grand engine of despotism.” Samuel Adams wrote in 1776, such a professional army was, “always dangerous to the Liberties of the People.” Soldiers were likely to consider themselves separate from the populace, to become more attached to their officers than their government, and to be conditioned to obey commands unthinkingly. The power of a standing army, Adams counseled, “should be watched with a jealous Eye.”

Experiences in the decades before the Constitutional Convention in 1787 reinforced colonists’ negative ideas about standing armies. Colonials who fought victoriously alongside British redcoats in the Seven Years’ War concluded that the ranks of British redcoats were generally filled with coarse, profane drunkards; even the successful conclusion of that conflict served to confirm colonists’ starkly negative attitudes towards the institution of a standing army. The British Crown borrowed massively to finance the conflict (the war doubled British debt, and by the late 1760s, fully half of British tax pokiesaustralian.com revenue went solely to pay the interest on those liabilities); in an effort to boost its revenues, Parliament began to pursue other sources of income in the colonies more aggressively. In the decade before the Declaration of Independence, Parliament passed a series of acts intended to raise money within the colonies.

That legislation further aggravated colonists’ hostility towards the British Army. As tensions between the colonies and the crown escalated, many colonists came to view the British army as both a symbol and a cause of Parliament’s unpopular policies. Colonists viewed the various revenue-generating acts as necessitated by the staggering costs associated with maintaining a standing army. The Quartering Act, which required colonists to provide housing and provisions for troops in their own buildings, was another obnoxious symbol of the corrupting power represented by the army. Many colonists held the sentiment that the redcoats stationed in the colonies existed not to protect them but to enforce the king’s detestable policies at bayonet-point.

No event crystallized colonists’ antagonism towards the British army more clearly than what became known as the Boston Massacre. In March 1770, British regulars fired into a crowd of civilians, killing five. That event provided all the proof the colonists needed of the true nature of the redcoats’ mission in the colonies. Six years later, the final draft of the Declaration of Independence contained numerous references to King George’s militarism (particularly his attempts to render the army independent of civilian authority, his insistence on quartering the troops among the people, and his importation of mercenaries to “compleat the works of death, desolation, and tyranny”); by the end of the War of Independence, hatred of a standing army had become a powerful and near-universal tradition among the American people; the professional British army was nothing less than a “conspiracy against liberty.”

Colonists’ experiences with British troops, and the convictions that sprang from them, help explain Madison’s reference to armies having traditionally “enslaved” the people they were commissioned to defend. After winning their political independence, the victorious colonies faced the difficult task of providing for their own security in the context of a deep-seated distrust of a standing military.

Madison’s use of the imagery of slavery points to the multiple meanings of that term in the 18th century. In Madison’s statement to the Convention, it referred not to the literal notion of armies marching the citizenry through the streets in shackles but to a kind of metaphorical slavery. The immense costs necessary to raise and maintain a standing army (moneys required for pay, uniforms, rations, weapons, pensions, and so forth) would burden the populace with an immense and crippling tax burden that would require the government to confiscate more and more of the citizenry’s wealth in order to meet those massive expenses. Madison’s language reflected a common concern that the maintenance of a standing army in the new United States would place similar burdens on the young government; their experiences with the British army under Parliament in the 1760s and 1770s likewise led to concerns that the executive would use a standing army to force unpopular legislation on an unwilling public in similar fashion.

Other members of the founding generation worried that an armed, professional force represented an untenable threat to the liberty of the people generally. Throughout history, the threat of military coup—governments deposed from within by the very forces raised to protect them—has been a frequent concern. In 1783, Continental Army officers encamped at Newburgh circulated documents that leveled a vague threat against Congress if the government continued its refusal to pay the soldiers. Historians generally conclude that a full-blown coup d’etat was never a realistic possibility, but the incident did little to assuage contemporary concerns about the dangers posed by a standing army.

The experience with professional armies during the 40 years before the Constitutional Convention, and the values that sprang from those experiences, helps explain why the founders never seriously considered maintaining the Continental Army past the end of the War of Independence. The beliefs that grew organically from their experiences with the British also help explain Madison’s passionate anti-military rhetoric (he would later refer to the establishment of a standing army under the new Constitution as a “calamity,” albeit an inevitable one); together, they cast a long shadow over the debates surrounding the kind of military the new nation would provide for itself.

Watch Professor Whitman Ridgway analyze the Bill of Rights in an Example of Historical Thinking

Kohn, Richard H. Eagle and Sword: The Federalists and the Creation of the Military Establishment in America, 1783-1802. New York: Free Press, 1975.

The Library of Congress. The Federalist Papers. Last accessed 6 May, 2011.

The National Archives. The Constitution. Last accessed 6 May, 2011.