Three issues are embedded in this query: U.S. foreign aid (giving our money away), collecting debts from abroad, and nations that helped the U.S. when we faced tough times. Let's take them up in order.

Foreign Aid

Since the 1960s, the U.S. has provided a bit under 30 percent of all funds developed countries have given to nations that are considered poor or otherwise economically worthy. Germany, France, and Japan together delivered another 40+ percent. Strategic importance is also a consideration. In U.S. expenditures, Israel and Egypt have received between four and five times the average of what is sent to other nations. This can be attributed to foreign policy concerns: the U.S. continued support of Israel, and Egypt's willingness to withdraw from Middle East hostilities toward Israel. ()

Another way to look at this is by comparing the amount of foreign aid with other expenditures. From the 1970s, non-military foreign aid has been less than half of one percent of U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP). By contrast, U.S. spending on health care stands at 16% of GDP, its share having risen for over a generation. () In addition, it should be noted that foreign aid is politically targeted money; cutting it to zero can do little to solve U.S. financial difficulties, but might create new political difficulties. The key conclusions are that foreign aid serves U.S. political and economic aims, including rewarding friends, and is a tool in a rivalry among developed countries for influence, respect, and, at times, access to key resources.

Collecting Debts

Trade debts are created when, collectively, an economy's firms buy more goods or services from abroad than they can sell to foreigners.

International debts may occur between states or between companies. They also may involve states owing sums to foreign firms/individuals or particular firms/individuals owing foreign states. Governments often issue interest-bearing bonds that other people or other governments buy; banks do the same. The governments and banks owe the bondholders their money back when the bond's time period expires (from a few months to 30-40 years). Trade debts are created when, collectively, an economy's firms buy more goods or services from abroad than they can sell to foreigners. Often in wartime, allied governments supply one another with materiel, keeping track of the values shipped and received. So how did this work out for the U.S. in the 20th century?

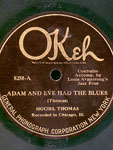

Working backwards, in World War I the U.S. supplied Britain and France with munitions and other supplies before it entered the conflict in April 1917, totalling over $7 billion, to which post-war loans for reconstruction added $3 billion. In part to pay back the U.S., Britain and France demanded that the "aggressor," Germany, deliver sizable long-term reparations (in cash and materials). This slowed German recovery and generated a political backlash that assisted Hitler’s rise. The Nazis, once in power, refused further payments to Britain, causing Britain to also stop payments to the U.S. These debts, the only ones now owed us by other nations, are uncollectable, although Britain’s World War II debts to the U.S. have been cleared, as was the final World War I reparations balance between Germany and Britain (2010). ()

We can't blame it on others, but it's also tough to take responsibility for how deeply we are in debt without anticipating long, hard decades climbing out of these holes.

As for trade debts, for 30 years after 1945, the U.S. sold more than it imported; thus firms elsewhere sent funds to make up the difference in goods and services totals. For the 35 years since 1975, our international clients have bought less from us than they have sold to us; hence we have to send dollars abroad to cover the difference. Since we neither reduced consumption or raised taxes to work off this imbalance, the value of our dollars fell in relation to the currencies of countries with different financial policies. () This makes many imports more expensive, encouraging foreign makers of, say, automobiles to build production plants in the U.S., though of course the profits aren't "ours." In 2011, neither governments nor firms owe the U.S. significant sums of money, relative to the size of our trade and budget deficits. Indeed, foreign firms own 47 percent and foreign governments another 25 percent of U.S. national obligations (particularly Treasury bonds). () This is why "cutting" spending is on many policy agendas, with some proposing "taxing" as well, precisely because it's up to us to figure a way out of this situation. We can't blame it on others, but it's also tough to take responsibility for how deeply we are in debt without anticipating long, hard decades climbing out of these holes.

Foreign Countries Offering Aid to the U.S.

3) A final note on others helping us in hard times: This has happened on occasion, but two examples stand out. In the second half of the 18th century, France stepped up to challenge Britain in North America, both in the French and Indian Wars and during the American Revolution, continuing an anti-England policy and costing their treasury dearly. The U.S. did not (and could not) step up to defend the French king during the French Revolution several years later. In addition, before the Civil War, local railroad builders needed foreign cash infusions to erect our first regional networks. State governments guaranteed these bonds, and the cash flowed in. When after the 1837 crash companies failed and states were called upon to back their guarantees with tax revenues, many defaulted, ruining both foreign investors and the U.S.'s financial reputation. Later, U.S. railroads struggled to find sufficient capital to build an integrated transport system for an industrializing continent. British and French capitalists came to our rescue, buying railway shares and bonds to fund construction and equipment. However, many of them received only trouble in return, as a full one-third of U.S. railway mileage fell into bankruptcy by the 1890s, necessitating wholesale reorganizations which ruined the value of many stocks and bonds.

A little history can help undermine any argument that other nations are ungrateful to America, as we've been there too. After World War I, our allies urged the U.S. to forgive the debts they owed to us, given that they had fought Germany for three long years. We said no, President Coolidge famously asserting that "They hired the money, didn't they." ()