Interpreting Political Cartoons in the History Classroom

A lesson that introduces a framework for understanding and interpreting political cartoons that can be used throughout your entire history course.

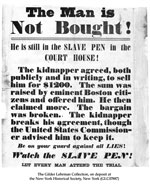

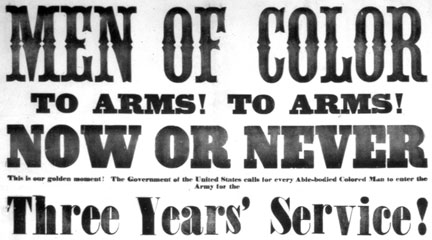

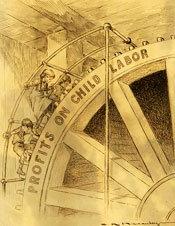

Political cartoons are vivid primary sources that offer intriguing and entertaining insights into the public mood, the underlying cultural assumptions of an age, and attitudes toward key events or trends of the times. Since the 18th century, political cartoons have offered a highly useful window into the past. Just about every school history textbook now has its quota of political cartoons. Yet some studies reveal that substantial percentages of adults fail to understand the political cartoons in their daily newspaper. How much harder then must it be for young people to make sense of cartoons from the distant past? The stark, simple imagery of many cartoons can be highly deceptive. The best cartoons express real conceptual complexity in a single drawing and a few words. Cartoons from the 1700s and 1800s often employ archaic language, elaborate dialogue, and obscure visual references. It takes a good deal of knowledge of the precise historical context to grasp such cartoons. In short, political cartoons employ complex visual strategies to make a point quickly in a confined space. Teachers must help students master the language of cartoons if they are to benefit from these fascinating sources of insight into our past.

A Cartoon Analysis Checklist, developed by Jonathan Burack, is presented here as a tool for helping students become skilled at reading the unique language employed by political cartoons in order to use them effectively as historical sources. The checklist is introduced through a series of classroom activities, and includes the following core concepts.

1. Symbol and Metaphor 2. Visual Distortion 3. Irony in Words and Images 4. Stereotype and Caricature 5. An Argument Not a Slogan 6. The Uses and Misuses of Political Cartoons

1. Make copies of three political cartoons taken from recent newspapers and magazines. Then make copies of three political cartoons from your history textbook. Try to choose clear, concise cartoons on issues familiar to your students. Plan explanations of any obscure references and allusions, especially in the historical cartoons, and identify background information about them that students will need. 2. Plan how you will group and pair your students for activities one and six. 3. Make copies for each of your students of the Cartoon Analysis Checklist and Documents 1-3. (If you are using the lesson with multiple classes, you need only make a class set of the first page of each of the handouts.)

1. Divide the class into two groups. Ask one group to discuss the contemporary cartoons and agree on a one-sentence explanation of each cartoon. Ask the second group to do the same for the historical cartoons. Stress that political cartoons are not like the comics. They are about social and political issues, and they express strongly held viewpoints about those issues. Emphasize that it is impossible to fully understand most political cartoons without some background knowledge of the issues they deal with. This is a preparatory exercise, so don't apply too strict a standard to judging what students come up with. The goal is to have them make initial interpretations on their own to see what that entails. 2. Have each group present its cartoons and explanations. Ask students to list any cartoon details they do not understand. Discuss whether their confusion is due to a lack of background knowledge or to something unclear about the cartoon itself. Finally, discuss the challenges of understanding historical cartoons as compared to the challenges of understanding contemporary political cartoons. 3. Explain that political cartoons use a special "language" to make strong points about complex issues in a single visual display. Various visual and (usually) written details convey a "message" designed to sway the reader. 4. Distribute the Cartoon Analysis Checklist. Explain that students can use it whenever they have to analyze a political cartoon. Go over the Checklist briefly. 5. Explain that students will work on six sets of handouts, each of which will illustrate one point on the Checklist. Distribute the first Document. Ask students to study the cartoon, read the background information on it and the relevant Checklist item. Add any additional information you think students may need. 6. Have students work individually or in pairs. Tell them to take notes in response to the questions on the worksheet (second page of each document handout). Share the ideas from these notes in a class discussion. 7. Repeat steps five and six with each of the six handouts (1-3 and 4-6).

- Students need to understand that political cartoons are expressions of opinion. They use all sorts of emotional appeals and other techniques to persuade others to accept those opinions. They cannot be treated as evidence either of the way things actually were or even of how everyone else felt about the way things were. They are evidence only of a point of view, often a heavily biased point of view.

- Students should not view their main task as deciding if the cartoon was right or wrong, though criticizing its bias can be a part of what they do.

- Just because cartoons are biased expressions does not justify student cynicism about using them as historical evidence. They can provide many kinds of evidence in a vivid, even entertaining way. Asking questions will encourage students to make inferences from the cartoon. Sample questions include: What conditions might have given rise to this cartoon? What groups might it have appealed to? What values does the cartoon express overtly or implicitly?

Other Political Cartoon Resources

Running for Office: Candidates, Campaigns, and the Cartoons of Clifford Berryman.

Teaching With Documents: Political Cartoons Illustrating Progressivism and the Election of 1912, a lesson plan which includes another political cartoon analysis guide.

The Library of Congress also has a fine collection of political cartoons by cartoonist Herb Block.

Burack, Jonathan. The Way Editorial Cartoons Work: A MindSparks Guide to Teaching Students to Understand Cartoons, revised ed. City: Social Studies School Service, 2000.

Fischer, Roger A. Them Damned Pictures: Explorations in American Political Cartoon Art. City: Archon Books, 1996.

Gombrich, E. H. "The Cartoonists Armoury," in Meditations On a Hobby Horse and Other Essays On the Theory of Art, edited by. . . , 127-142. City: Phaidon Press, 1994.

Parker, Paul, Ph.D. "American Political Cartoons: An Introduction."Paul Parker, Ph.D. 12 April 2000. http://www2.truman.edu/parker/research/cartoons.html#top.

Tufte, Edward R. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, 2nd ed. City: Graphics Press, 2001.