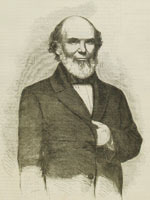

The original of this handbill is in the Boston Public Library’s Rare Book collection. It is part of the papers, manuscripts, and diaries of abolitionist and controversial Unitarian clergyman Theodore Parker, who composed it and had it printed and distributed.

Boston Vigilance Committee

At the time he posted it around Boston, Parker was the head of the Boston Vigilance Committee, a group of white and black abolitionists, eventually numbering more than 200, who agitated in various legal and extra-legal ways to frustrate slaveholding. The committee set up a secret network of operators on the Underground Railroad, who transported escaped slaves through the area. The committee also looked for slave-catchers in Boston who had come north to search for fugitive slaves. Parker and his fellow committee members alerted the sympathetic white and black community in the area, and sometimes threatened the slave-catchers and scared them off, and even rushed the jail to free captured slaves.

The committee’s semi-secretive efforts increased in intensity after the 1850 passage of the Fugitive Slave Act (part of the Compromise of 1850), which specifically required Northern states to remit or return fugitive slaves to their Southern owners. The committee’s collective outrage peaked during the 1851 trial and return to Georgia of escaped slave Thomas Sims (the handbill is from this period), the capture and freeing of fugitive slave Shadrach Minkins in 1851, and the riots during the capture and return under Federal guard of fugitive slave Anthony Burns to Virginia in 1854.

Top Eye Open

Having or keeping your top eye open simply meant keeping a careful watch, no matter what else you were doing. It most often carried the idea that you had to keep a lookout for threatening intruders, enemies, or competitors.

The phrase appears to be an Americanism. I see written evidence for its use, among both uneducated and educated and among both whites and African Americans, as early as 1828 and as late as 1911. Those who used it probably felt it to be a bit unusual because it often appeared with quotation marks around it, as if they understood it as slang.

Today, we would say something like “keep your eyes peeled” or “keep one eye open” or “sleep with one eye open.” When you lie down to sleep, one eye is uppermost and is therefore your “top eye,” the one with the slightly better vantage point. “Top” probably also connoted “best,” so that your “top eye” was the one that could see farther and clearer.

Having or keeping your top eye open simply meant keeping a careful watch, no matter what else you were doing.

John S. Skinner, for example, in an 1828 issue of The American Farmer, counseled his readers, “So that as small sands form the mountain, and economy is said to be wealth, perhaps it would be as well to keep our top-eye open a little sharper towards those smaller items of family expenses.” The satirist John S. Robb, in a backwoods story he published in an 1845 issue of The Spirit of the Times, had one of his rustic characters say: “You, Mike, keep your eye skinned for Ingins, ‘cause ef we git deep in a yard here, without a top eye open, the cussed varmints ‘ll pop on us unawars, and be stickin’ some of thur quills in us—nothing’ like havin’ your eye open and insterments ready."

The phrase was a warning to keep your guard up, but also simply to pay close attention to what was happening so that you could forestall a threat as it arose and even shrewdly turn the situation into a favorable opportunity for your own success or profit.

Theodore Parker’s Use of the Phrase

Theodore Parker certainly understood the phrase in this way. In a speech he gave to the annual meeting of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society in 1853, he said, “I am glad that a ‘top eye’ is open to scrutinize the acts of public men—an eye that never slumbers nor sleeps—an eye that does not spare a friend when he falters more than a foe when he is false; I am glad of that.” And in a letter he wrote in 1854, Parker facetiously chided fellow abolitionist Samuel J. May for having tried to argue that the Bible was a pacifist tract, when there was plenty of evidence to the contrary: “But all this, O father! is a delusion of Satan, who will deceive the very elect if they do not keep a top-eye open and a bright look-out.”

The phrase also had currency among other abolitionists, who used it to describe slaves who carried on with their normal activities, but constantly watched for the moment when they could act by making their escape. The Provincial Freeman in its issue of April 21, 1855, for example, used the phrase:

The cook (a colored man) having his “top eye open,” kept quiet till the steamer had fairly reached New York, then quietly procured a carriage, and apprised the property [that is, a slave onboard] that it was at liberty to assume a more independent air; consequently, it was not unconscious of the value of time; and lo! to the utter amazement of the Mate, it was seen making quick paces in the direction of the carriage.

Abolitionist activist and writer William Still, in his 1872 history, The Underground Rail Road, described the rescue of a slave, Jane Johnson, and her children, using the phrase—“Jane had her ‘top eye open,’ and in that brief space had appealed to the sympathies of a person whom she ventured to trust, saying, ‘I and my children are slaves, and we want liberty!’”

The phrase “keep (or have) your top eye open” had this meaning all during the time it was current, through the first decade of the 20th century.

Another Later Meaning of the Phrase

For about 15 years, from about 1885 to 1900, long after Parker had written his handbill, the phrase briefly developed another meaning before it dropped out of currency altogether. Liberal reformers and spiritual progressives, especially from New England, used it to refer to cultivating a new and higher angle of vision on the world. To keep or have your top eye open meant to look a little deeper into the reasons of things or to look behind the surface of everyday things, to take your eyes off the ground and look into the air, up to heaven, to look there for subtle signs and omens, to be high-minded, to be spiritual rather than materialistic, to be focused on the true and lasting rather than the false, the sensual, and the transitory, on the intuitive rather than the calculating.

Parker’s use of the phrase in 1851 has nothing in it, even implicitly, that connects it to this later meaning. However, the distant origins of the image that this later meaning captures probably lay in Parker’s friend and fellow Transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay, “Nature,” written in 1836, where he described an “exaltation” he experienced one day at twilight staring into snow puddles: "Standing on the bare ground—my head bathed by the blithe air and uplifted into infinite space—all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or parcel of God."

"I become a transparent eyeball"

The “top eye” was the “skylight of the soul,” like the oculus at the top of the Pantheon in Rome. It saw, not the waves, but “Him who walks upon the waves,” in the words of ex-Quaker, Temperance worker and suffragist Hannah Whitall Smith. For her, opening one’s top eye was a mystical experience, a religious conversion, a reception of holiness and sanctification into one’s life. In 1883, Smith’s coworker and friend, Frances Elizabeth Willard, the President of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, described Mrs. Smith’s home and family:

There is no fear of the “next thing,” because it is the next and not the last. There is no looking back, after the puerile fashion of Lot’s wife, but, with earnest gaze forward and upward, this family group moves forward, blessing and blessed. “Keep your top eye open,” is the mother’s constant motto for her children.

About the same time, Congregationalist lecturer, Joseph Cook, at one of his weekly prayer meetings at Boston’s Tremont Temple, told his audience:

British advanced thought believes in its frontal eye, but not in its coronal eye. This is a defect of the English mind and of the American. When you reach India, in your tour of the globe, you will find people who believe in their coronal eye; who see God in an intuitive way, as Emerson did. … The Scotch have an eye in the dome of their souls; but they have such an immense front window that they are chiefly occupied in gazing out of it. Rarely, except in periods of mighty religious fervor, do they look aloft through the dome. … In general, Scotchmen, Englishmen, and Americans believe in experience, observation, definition, induction, the scientific method, and nothing else. You notice thus one of the defects of Anglo-Saxon advanced thought, that it sees with its front eye, and not with its top eye.