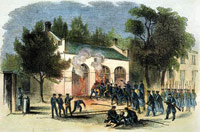

With iconic historical events such as the Boston Massacre it can be difficult to separate historical fact from myth. This lesson acquaints students with some of the subtleties of constructing historical accounts. It allows them to see firsthand the role of point of view, motive for writing, and historical context in doing history. The lesson opens with an anticipatory activity that helps illustrate to students how unreliable memory can be, and how accounts of the past change over time. Students then analyze a set of three different accounts of the Boston Massacre: a first-hand recollection recorded 64 years after the fact, an account written by an historian in 1877, and an engraving made by Paul Revere shortly after the event. We especially like the fact that with the first document, the teacher models the cognitive process of analyzing the source information by engaging in a “think aloud” with the document. This provides a great opportunity to uncover for students the kinds of thoughts and questions with which an historian approaches an historical source. The primary source reading is challenging, and students will likely require significant additional scaffolding to understand the meaning of the texts. Teachers may want to consider pre-teaching some of the difficult vocabulary, excerpting or modifying the text, or perhaps reading the text dramatically together as a whole class.

The Boston Massacre: Fact, Fiction, or Bad Memory

Students attempt to assign responsibility for the Boston Massacre through careful reading of primary and secondary sources and consideration of such issues as who produced the evidence, when it was produced and why was it produced.

Yes

Yes

The image linked in the “materials” section offers valuable supplemental information for teachers. But minimal background information is provided for students.

Yes

Teachers will have to plan carefully to help students read the challenging texts. In addition, teachers may want to augment the writing portion of the lesson; the extension activity provides a great opportunity for this.

Yes

Teacher models a “think aloud” with the first document. Students replicate the process first in groups, and then individually.

Yes

Identifying and evaluating source information is a key element of this lesson.

Yes

While appropriate for elementary school students, it could easily be adapted for middle school.

No

Very limited vocabulary support is provided. Teachers will have to read aloud or otherwise provide additional scaffolding to assist students in understanding the documents.

Yes

The assessment activity provided is not thorough, and no criteria for evaluation are provided. However the extension activity provides a splendid opportunity for teachers to assess how well students have acquired the skills taught in the lesson, as well as an opportunity for students to see that these skills may be used in other situations and contexts.

Yes

Yes

Historical Agency in History Book Sets (HBS)

A strategy that combines fiction and nonfiction texts to guide students in analyzing historical agency.

Authors of historical fiction for children and adolescents often anchor their narratives in powerful stories about individuals. Emphasis on single actors, however, can frustrate students’ attempts to understand how collective and institutional agency affects opportunities to change various historical conditions. History Book Sets (HBS) that focus on experiences of separation or segregation take advantage of the power of narratives of individual agency to motivate inquiry into how collective and institutional agency supported or constrained individuals’ power to act.

History Book Sets combine a central piece of historical fiction with related non-fiction. By framing a historical issue or controversy in a compelling narrative, historical fiction generates discussion regarding the courses of action open not only to book characters, but to real historical actors. Carefully chosen non-fictional narratives contextualize the possibilities and constraints for individual action by calling attention to collective and institutional conditions and actions.

- Select a piece of well-crafted historical fiction that focuses on a historical experience of separation or segregation (NCSS Notable Books is a good place to start). The example focuses on Cynthia Kadohata’s (2006) Weedflower—a story that contrasts a young Japanese-American internee’s relocation experience with a young Mohave Indian’s reservation experience.

- Select two pieces of related non-fiction that provide context for the historical fiction. Non-fiction should include courses of action taken by groups and institutions, as well as individuals. This example uses Joanne Oppenheim’s (2007) “Dear Miss Breed”: True Stories of the Japanese American Incarceration During World War II and a Librarian Who Made a Difference and Herman Viola’s (1990) After Columbus.

- Select photographs that visually locate the events in the literature. Duplicate two contrasting sets of photographs.

- Reproduce templates for poem (Template A) and recognizing agency chart (Template B). The recognizing agency chart works best if students begin with an 8½x11 chart and then transfer their work to larger chart paper.

- The time you need will depend on whether you assign the historical fiction for students to read or use it as a read-aloud. Reading a book aloud generates conversation, ensures that everyone has this experience in common, and lessens concerns about readability. If students read the book independently, plan on three class periods.

- Recognizing Changing Perspectives. In making sense of historical agency, it helps if students recognize that different people experience historical events differently. For instance, the main fictional characters in the example have quite distinct views of relocation camps. The packets of photographs help children interpret changing perspectives, and the biographical poem provides a literary structure for expressing their interpretations.

-

- Organize the students in pairs. Give half the pairs Packet A (Japanese Experiences); half Packet B (Indian Experiences). Students write captions for the pictures explaining how the experiences pictured influence characters’ view of the relocation camp.

- Drawing on their discussion and readings, each pair of students writes a biographical poem (see Template A) representing how their character’s ideas and attitudes change over the course of the story.

- Display captioned pictures and poems where students can refer to them during the next activity.

-

- Recognizing Agency: What Can be Done?

-

- Distribute Recognizing Agency chart (Template B). Work through the chart using a secondary character in the historical fiction as an example.

- Assign pairs of students to a fictional or historical participant. For example, students might investigate the fictional main character or a family member or friend or students could investigate a historical participant.

- Display charts. Discuss:

- Why do some people, groups and institutions seem to have more power than others?

- How can people work most effectively for change?

- Can you identify strategies used to alter other historical experiences of separation or segregation?

-

- Agency Today. After considering the kinds of agency expressed by people during the past, students might write an argument for or against contemporary issues that surround the topic. For instance in the example, students investigate efforts to restore the relocation camp.

- Book selection presents the most common pitfall in developing and using an HBS. Historical fiction presents a two-pronged challenge: If the narrative in the historical fiction does not hold up, good historical information can’t save it. On the other hand, a powerful narrative can convince students of the “rightness” of very bad history. Never use books you have not read! With that in mind:

-

- Make sure you check out reviews of historical fiction and non-fiction (i.e. Hornbook, Booklinks, Notable Books) or more topic-specific reviews such as those provided by Oyate, an organization interested in accurate portrayals of American Indian histories.

- Choose non-fiction emphasizing collective and institutional agency that contextualizes actions in the novel.

-

- Because students’ identification with literary characters can be quite powerful, use caution in identifying one historical group or another as “we.” Implying connections between historical actors and students positions students to react defensively rather than analytically. None of your students, for instance, placed people in relocation camps or on reservations, but referring to past actions by the U.S. government as something “we” did can confuse the issue. Students are not responsible for the past, but as its legatees they are responsible for understanding what happened well enough to engage in informed deliberation about the consequences of past actions.

- Historical Book Sets are designed to work against tendencies to overgeneralize about group behavior (i.e. assuming all European Americans supported internment). In response to overgeneralization, ask for (or point out if necessary) counter-examples from the book set. Occasional prompting encourages students to test their generalizations against available evidence and to think about within-group as well as between-group differences.

- Historical Agency: Internment and Reservation at Poston. Background for the teacher: Groups and individuals exercise power differently, depending on the social, cultural, economic, and political forces shaping the world in which they are acting. In the case of the internment and reservation systems, for example, the power of Japanese-Americans to resist internment was quite different from the power of the War Relocation Authority to enforce relocation. Or, consider that the options available to Japanese men were quite different from those available to women or to the Native American residents of the Poston reservation. Introducing the concept of historical agency—what action was possible given the historical moment—can be a powerful tool for making sense of past behaviors. Power is a familiar concept to students who, with relatively little prompting, understand not only that larger forces may limit or expand opportunities for action, but that individuals may not all respond in the same way to those opportunities. Beginning by recognizing different perspectives on an event prepares students to consider why people might take different action, and comparing responses to action prepares students to consider available options for expressing agency. This, in turn, reinforces an important historical understanding: nothing happens in a vacuum. By placing so much attention on individual agency (often some hero or heroine), history instruction too often ignores persistent patterns of collective and institutional agency. This is not to dismiss narratives of individual agency. This HBS begins with Sumiko’s and Frank’s story because individual agency captures students’ interest and engenders a level of care that motivates further investigation of the differential agency expressed by the individuals, groups, and institutions that framed Sumiko’s and Frank’s historical choices. * Agency refers to the power of individuals, groups, and institutions to resist, blunt, or alter historical conditions. Differential agency refers to differences in potential for and expression of power within and between individuals, groups, and institutions.

Bamford, Rosemary A. and Janice V. Kristos, eds. Making Facts Come Alive: Choosing Quality Nonfiction Literature K-8, 2nd ed. City: Christopher-Gordon Publishers, 2003.

Levstik, Linda S. and Keith C. Barton. Doing History: Investigating with Children in Elementary and Middle Schools. London: Routledge (2005).

Online U.S. History Textbooks

Do you know of any good online US history textbooks?

Online textbook options are convenient, inexpensive, and environmentally friendly. The key is finding one that is reliable, meets the needs of your students, and complies with district standards—so you will want to explore some to find one that fits your needs. We know of a few online textbooks that will help you get started in your search. Digital History, a project hosted by the University of Houston, offers an easy-to-use, high-quality textbook. Digital History is also a good resource for supplementary classroom materials including primary sources, e-lectures, and lesson plans. USHistory.org, created and hosted by the non-profit Independence Hall Association, also offers a complete illustrated U.S. history text that is clearly organized by topic and easy for students to use. A third option is the Outline of U.S. History, which is produced and maintained by the U.S. State Department. The Outline is a fairly comprehensive textbook, and is accompanied by useful supplementary resources, including historian essays and a briefer version of the textbook. Finally, Wikibooks offers a U.S. history textbook that is fairly comprehensive and easy to use. On a cautionary note, Wikibooks is an open source site (like Wikipedia), so teachers will want to carefully monitor the content of the site to be certain that the material is accurate and useful.

Foundations of American History: John Brown Song

Foundations of U.S. History, Virginia History as U.S. History features 4th graders learning about John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry through analyzing the song "John Brown's Body." Video clips of classroom instruction accompany short videos of a scholar analyzing the song and the teacher reflecting on the lesson. The John Brown song is one of eight documents found on the Source Analysis feature of the Teaching American History grant website in Loudoun County, Virginia. In the classroom practice section for John Brown's Body we see students analyzing the song to understand how northerners viewed John Brown shortly after his raid on Harpers Ferry. This video provides examples of two promising practices:

- Close analysis of a song as a primary source

- Consideration of whether views expressed in that source represent all perspectives.

The lesson starts with the teacher playing the song "John Brown's Body." In this warm-up activity, the teacher instructs students to draw a picture of "what you see in your mind." After students share their drawings, the teacher provides them with a worksheet to help students analyze the musical composition. Next, students analyze the lyrics to an adapted version of the song written in 1861. The teacher works with individual students to help them use prior knowledge to make sense of the song and generate questions about the song. This progression from open-ended student task to close historical analysis engages and challenges students.

Towards the end of the lesson, the teacher facilitates a whole-class review of the Guiding Question worksheet. After students share that they think the song portrayed John Brown as a hero, the teacher refers back to a prior lesson asking, "Do you think this song represents how everybody in the North feels?" Students respond that it does not. The teacher uses this conversation as an opportunity to review that many people in the North did not support John Brown's tactics. Students see that while primary documents are valuable evidence, they should not assume that an individual source speaks for all people. This lesson also draws on multiple classroom resources and incorporates a variety of historical thinking skills. Students use their textbook to help them make sense of the song: they consider the song's historical context and audience. Additionally, you can find a comprehensive lesson plan, complete with additional primary sources, background information, and classroom worksheets, on the site.

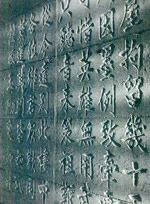

Discovering Angel Island: The Story Behind the Poems

Students explore the immigrant experience at Angel Island through the analysis of poetry written by immigrants during detention at the San Francisco Bay island.

Many U.S. history classrooms devote significant time to understanding the immigrant experience. In teaching the immigrant experience, however, many classrooms focus exclusively on European immigration through Ellis Island. This lesson, The Story Behind the Poems, provides students with an excellent opportunity to learn about Asian immigration through Angel Island, and the ways in which the Asian immigrant experience differed from the European immigrant experience. The topics covered in this lesson would be an excellent addition to a unit on immigration, and would couple nicely with lessons on Chinese Exclusion and nativism in the West. The lesson first provides students with excellent historical background through an on-line video about Angel Island. The lesson then positions students to better understand the Asian immigrant experience through an analysis of poetry left by Asian immigrants on the cell walls of Angel Island. The poetry analysis allows students to connect with the words of the immigrants and hone the skill of analyzing the perspective of an author in a literary piece from the past. The lesson is highly structured and provides plenty of guidance for teachers who are not experienced in using poems as primary historical documents. The lesson includes sample questions to pose with students while analyzing the poems and also provides students with a graphic organizer to help them organize their thoughts as they prepare to write a reflection on a poem.

Yes The background and resources are historically accurate and contain links to supplementary materials.

Yes A high-quality video introduces students to the immigrant experience at Angel Island and is also a great resource for teachers who are teaching about Angel Island for the first time. Comparative immigration timelines are also excellent resources.

Yes Students interpret poems and write a reflection on the meaning of the poem and the perspective of the author.

Yes

Yes The poetry analysis requires close attention to meaning and intent.

Yes This lesson is appropriate for the students in late elementary to early middle school.

Yes Materials include teacher guidelines for helping students analyze the poems and a graphic organizer to help students organize and focus their thoughts about the poems.

No Students are assessed based on in-class discussion and a written reflection about the poems. However, the lesson does not provide specific criteria for assessing performance on the reflection.

Yes The lesson-plan is clear and can be easily adapted to a wide variety of classroom settings.

Yes The lesson aims to 1) teach about the Angel Island experience, and 2) provide opportunities to analyze and interpret poetry. The lesson progresses logically to these goals.

Evaluating the Validity of Information

Students learn to assess the validity of a historical argument as they evaluate the implausible theory that the Chinese discovered America in 1421.

TV presents a great deal of historical information these days, but not all of it is valid or trustworthy. Unfortunately, many students lack the tools needed to assess historical information they see on television. This skill-building lesson presents students with some of the tools needed to assess the validity of an argument made through a persuasive, high-quality visual medium. In this two-day lesson, students assess the validity of a claim integral to the argument that the Chinese discovered America in 1421. Retired submarine commander Gavin Menzies presents this argument and the evidence to students in two short video clips highlighting the resources available to ancient Chinese sailors to make seven epic ocean voyages during the Ming dynasty. The lesson is clearly structured and guides students through steps they should take to evaluate historical claims. Helpfully, it includes a student handout that clearly explains the criteria for assessing the evidence of a historical argument. For example students are prompted to look at the qualifications of the person making a claim and to evaluate the persuasive techniques being used. A second handout has a worksheet to help students use the criteria to evaluate specific aspects of Menzies's argument. Student learning is assessed both through classroom discussion and a culminating essay that prompts students to provide a reasoned evaluation of the claim that the Chinese had the naval capacity to travel to America in the 15th century. The lesson includes a detailed rubric to assist your evaluation of these essays.

Yes The process of examining historical evidence is presented accurately. However, other websites present additional information and arguments disputing Menzies' thesis.

No The lesson provides clear criteria for assessing historical accuracy but provides little historical background about the specific time period under investigation.

Yes Students write a final essay, but the lesson does not require significant reading.

Yes Lesson requires students to analyze the evidence.

Yes Requires close attention to the arguments made in a historical video. Attention to the source of a historical argument is an integral part of the lesson.

Yes Appropriate for grades 6-8. Could easily be adapted for grades 9-12.

Yes Provides a well-written student handout of criteria for assessing the validity of a historical argument. A table to help students apply these criteria to Menzies's theory is also provided.

Yes The lesson provides a solid essay prompt and a clear rubric for assessing the essay.

Yes Directions are clear and procedures are realistic in most settings.

Yes The lesson progresses logically toward the goal of making students think about historical evidence.

What is it?

Twitter is a social networking tool for almost-instant communication through the exchange of quick, frequent messages. People write short updates, often called 'tweets' of 280 characters or fewer. Tweets are available to the general public or communicated more specifically as users join groups—as followers or followed by others in networked communication. Twitter users continue to expand its diversity and application. For teachers, Twitter can offer professional support, instant communication with students, and creative approaches to disseminating course content.

Twitter's own forum, Frequently Asked Questions, gives a concise, comprehensive view of what it is and how to use it. To establish a Twitter account, simply follow the sign up icon to the Registration page where you're asked to enter your name, a username, and password and to agree to the terms of service. Multiple accounts are possible if you choose to separate business, family, and friends.

But does Twitter have value as an educational tool, or is it another cog in the wheel of communication overload? Quick Start Tips Information includes methods to use Twitter tools and software to enhance Twitter's application. The conclusion: "Twitter is an incredibly powerful tool for your personal learning, connecting with others and complements your blogging." The Power of Educational Technology blog offers Advice for Teachers New to Twitter—including links to other twittering teachers with comments, problems, and suggestions. These tips stress the value of Twitter as a professional communication and development tool. The Twitter4Teachers Wiki helps educators link with others in their specific discipline or field such as social studies teachers, geography teachers, retired teachers, school principals, and more.

Among the reasons Twitter may be more useful for professional networking and professional development than as a classroom tool is cost and accessibility.

As The Wired Campus in the Chronicle of Higher Education points out: Twitter costs money—while it works with internet access, the immediacy of the text messaging facility of mobile phones maximizes its use.

For some educators, however, Twitter has become a useful classroom tool. Can We Use Twitter for Educational Activities?, a paper presented at the Fourth International Scientific Conference, eLearning and Education (Bucharest, April 2008), focused on arguments for and against the microblogging platform in education. Twitter is about learning, according to authors Gabriela Grosseck and Carmen Holotescu, but they are clear that guidelines and parameters are critical to successful educational application—as they are with any learning tool. The article looks at examples of Twitter in the classroom and concludes with an extensive bibliography of online resources about educational uses of Twitter. For older students, Twitter is another tool that can encourage enthusiasm through communication and promote collaborative learning—as well as provide another opportunity to stress responsible use of networking tools.

In Twitter in the Classroom, a Vimeo posting, Christine Morris discusses issues related to uses of Twitter and initial problems with the interface and application—and how these software and training problems were solved. While educators frequently ask about the use of Twitter in the K–8 classroom, examples are few and its value, inconclusive. K-3 Teacher Resources offers an enthusiastic step-by-step guide—including a description of the learning curve and tips on Twitter etiquette. Twitter in the Classroom is a series of educational screencasts on YouTube discussing among other points, the use of hashtags and backchannels.

VoiceThread

VoiceThread is a popular web-based tool for creating and collaborating on multimedia presentations. Voicethread allows you to create a presentation combining images and video with text and audio commentary. The internet safety component is comprehensive; access to accounts and student work is carefully controlled. It's recognized by the American Association of School Librarians (AASL) as a tool and resource of "exceptional value to inquiry-based teaching and learning."

First, you'll need to setup a Voicethread account through the link in the upper right hand corner of the home page.

You can experiment with the program and create up to three VoiceThread projects free of charge. (Fees are nominal for classrooms and for school-wide accounts.)

Five choices are available for adding audio: computer microphone, telephone, text, audio file (mp3 or WAV), and webcam. You'll need a microphone if you're using your computer, and Voicethread provides instructions for setup and use and comment moderation.

The About page gives directions for using VoiceThread's presentation tools and K-12 solutions gives instructions especially for K-12 classrooms and answers questions such as "How do I add students to my school or class subscription?"

Once you've created your Voicethread account, search for curriculum-related sample projects on the Browse page to get an idea of the possibilities.

- The Town of Corte Madera is a second grade local history project from California.

- Escape on the Underground Railroad is the work of a fifth grade class and demonstrates the integration of voice, teacher annotation, and visuals.

- 8th Grade Child Labor Investigation is an audiovisual lesson plan presented by a teacher and explaining one school's across-the-curriculum approach to the industrial revolution.

As you create a test project, you'll have the option of uploading images from your computer, Flickr, Facebook, or directly from among 700,000 digitized photos from The New York Public Library. The Voicethread blog discusses these import possibilities.

Staff members at the New York Public Library also have created learning modules, grouping historical images and other primary sources by themes and categories with audio commentary from historians and archivists.

Voicethread's digital library contains articles by teachers about classroom projects—including sections with helpful caveats on challenges and setbacks in implementing their lesson plans.

For further tutorials and examples beyond the VoiceThread site, visit this educational review written by a New Zealand educational technology specialist.

Visit YouTube and search with the term Voicethread to uncover tutorials such as Embedding Voicethread productions in blogs

Applying KWL Guides to Sources with Elementary Students

KWL Guides—what do I know, what do I want to know, what have I learned—offer a straightforward way to engage students in historical investigation and source analysis.

Using KWL guides in elementary history classes empowers students and teachers.

- KWL guides engage students via a simple format. They place the students' observations, questions, and knowledge development at the center of exploring historical sources. Students are able to connect new knowledge to prior knowledge, and generate and investigate questions.

- Most elementary teachers are familiar with KWL guides to structure inquiry in various subjects, from literature to science, but analyzing primary historical sources can be a new experience, leaving teachers hesitant to incorporate them in their teaching. Applying the KWL approach to primary source analysis encourages teachers to adopt a constructivist approach to history instruction, as it taps their confidence in using a familiar strategy to teach a new subject.

The KWL chart is a metacognition strategy designed by Donna Ogle in 1986. It prompts students to activate prior knowledge, generate questions to investigate, and inventory the new knowledge that emerges from investigation. The acronym stands for: K: students identify what they already KNOW about a subject. W: students generate questions about what they WANT to learn about the subject. L: students identify what they LEARNED as they investigated. In lower elementary history studies, the entire class looks at projected images or documents and together fills out a KWL chart. In the middle grades teachers may model the process. Once students gain proficiency, they are allowed to work in pairs or groups. Primary sources can be incorporated at various times during a history lesson. Teachers may use them to introduce a unit or to expand a student's understanding and empathy for a topic. Directions below describe how to use the KWL primary source analysis during a unit, but they are easily adapted to use at the start of a unit.

- Choose a source to explore with your students. Books in school or public libraries also offer historical images and documents.

Source Subject When seeking images, artifacts, or written documents that align with your history unit, consider four ways that primary sources enhance history learning:

- Motivate historical inquiry

- Supply evidence for historical accounts

- Convey information about the past

- Provide insight into the thoughts and experiences of people in the past (1)

Your source should match one or more of these criteria; they are not mutually exclusive. You may find a source that you believe will motivate your students' learning and it also provides a vivid, intriguing glimpse into the experiences of people in the past. Or you may choose to examine with your class a source cited as evidence in one of the historical accounts that you read together, and then discover the source conveys additional information about your topic. Source Format In terms of primary sources, elementary schoolchildren often engage most successfully with visual images, especially pictures that feature children or dramatic action. Don't discount written documents, however, especially in the middle grades, although you might need to abridge a lengthy document or model the process of paraphrasing with short excerpts.

- Copy the source to an overhead transparency or into a file for an LCD projector. You can give students their own copies to view at their desks and put in their history folders, and post one on the class's history timeline.

- Decide when you will examine the source. To scaffold source explorations, schedule them between reading historical fiction and/or nonfiction to provide context.

- Decide how to display and write on the class KWL chart. Using a transparency is fine, but could limit ongoing student access to the chart. ]KWL charts can be constructed on poster boards, whiteboards, or butcher paper for permanent display; these can be added onto as you explore other elements of your history unit. The posted chart is a visual reminder of students' growing prior knowledge as they move on to investigate other sources. When they are asked to interpret new sources, they can reference what they have studied previously. For students working in groups, make copies of the KWL chart for all students.

1. Review the class's history learning to this point. Have students take turns walking and talking sections of your unit timeline, or ask students to brainstorm important themes they have explored thus far. In middle elementary, ask students to pair up and explain to another student what they learned the previous day. For lower elementary, call on students at random to share their thoughts with the whole class. 2. Following this review, explain that students can explore more about (the unit topic) by studying an information source from the actual time of the historic event. To illustrate this idea, contrast the date of the source you are examining with the copyright date of a fiction or nonfiction book you have read to your class. Eventually, at the end of this activity, you will return to the book and help your students understand how its author may have examined primary sources as s/he prepared to write it. 3. Introduce the KWL chart with knowledge questions as a guide to explore a source. If you have not used a KWL before, or if students are not familiar with the format, explain what the letters stand for and how they help us look closely at a source of information, make a list of what we already know about the source, and ask questions to help us learn more. 4. Model the KWL process with the entire class. Project a source via LCD or overhead projector. Conduct the K portion of your KWL (what do I think I already know about this source). After students carefully read or view the source, brainstorm a list of things they know about the image, artifact, or document. To help students activate their knowledge, structure interactions with sources by asking:

What/who do you think is in the source? (inventory the objects in an image or the components of a written source) What do you think is happening? (summarize the action or meaning) When do you think it is happening? Why do you think it is happening? Why do you think someone created the source in the first place? How did you come up with your answers? If people appear in the document or image, how do you think they felt?

5. Conduct the W portion (what do I want to know and how can I find out more). Ask students to:

Brainstorm aspects of the source they are uncertain about Brainstorm a list of questions about the source itself Brainstorm how they might find answers to their questions

6. Conduct the L portion of your KWL (what I've learned about or from this source).

Seek answers to the questions, or return to them as you investigate other sources and topics for your history unit and as answers emerge from those explorations. If you decide to investigate some questions right away, have the entire class work together, or divide students into groups and assign each group a question to investigate. Groups can use such research resources as the internet, school media center, or oral history interviews. Give the groups any books related to their question. When you send groups to the media center/library, alert your media specialist in advance so s/he may assist students with their searches. This activity is an excellent way to introduce or reinforce the use of search engines, tables of contents, and indexes to locate information. Update the guide by inventorying what your students have learned about the source and about the larger history topic by studying this source.

7. Brainstorm and take inventory of remaining unanswered questions raised by students while investigating the source.

Extend learning for better readers. Ask them to decipher and summarize the document. They can then share their results with the rest of the class. If you determine a document is too difficult for any of your readers to decipher, create a simpler version for students to study.

- Copying images. Sometimes it's difficult to get a good copy. File size and type vary and may affect the quality of a reproduced image. If you find an image you want to use but it does not copy clearly, try using Google or another internet image search engine to locate that image in a different format or size.

- Selecting documents. When a document is only available in an original handwritten form, deciphering it can pose a challenge for teachers as well as students. Try to find documents that have been transcribed into readable type.

- Some documents are beyond the comprehension level of those students who read at or below grade level. If you want to use a source that fits this scenario, try the following:

- A common pitfall in executing KWL is the inclination to close discussion following the L step. Authentic learning exploration begins and ends with questions. When teachers demonstrate that it's natural and desirable to have ongoing questions, they send the message that questions are a crucial part of education. Asking questions doesn't indicate a lack of knowledge, but is evidence of an active mind. To honor questioning as the foundation of learning, KWL should perhaps add a fourth step: Q.

KWL Image Exploration: Segregated Public Places The history of Jim Crow laws in the U.S. is the history of segregated neighborhoods, schools, public areas, hotels, restaurants, marriage, transportation—essentially every aspect of daily life. Though these practices were outlawed by civil rights legislation in the 1960s, their legacy of poverty and prejudice persists. It is essential that today's students not only learn the history of segregation but care about its aftereffects. Photos of Whites Only and Colored signs on water fountains, restrooms, waiting rooms, and entrances to buildings are powerful resources that engage student empathy for the African American experience under Jim Crow. This KWL photo analysis is most effective when preceded by explorations of pre-slavery African cultures, slavery, the Civil War, the 13th and 15th Constitutional Amendments, and sharecropping. As the first activity that explores segregation laws, it illustrates the reality of separate public accommodation as humiliating, degrading, and a clear signal that not all people were considered equal in America.

Credit for first using KWL as a historical source analysis guide goes to the second- and third-grade teachers who piloted the Bringing History Home curriculum at the Washington Community School District in Washington, Iowa. These teachers came up with KWL as a simple alternative to the NARA historical analysis guides. I am, as always, deeply indebted to BHH teachers for their innovative, inspired ideas.

See the essay Teaching Segregation History as you consider how students may react to the topic.

The materials you need to conduct this activity include a photo of segregated drinking fountains and a KWL chart. Two forms of the chart are provided: an empty one and one supplied with K questions.

For more resources about KWL guides please see Bringing History Home.

For further reading, try ReadingQuest.org's "Strategies: Making Sense in Social Studies" and Bringing History Home's bibliography of selected websites with resources for teaching segregation history.

Chen, Jianfei. "Online Course L517: Advanced Study of the Teaching of Secondary School Reading." Indiana University. Last modified January 2008.

Ogle, Donna. "K-W-L: A Teaching Model That Develops Active Reading of Expository Text." The Reading Teacher 39 (1986): 56470.