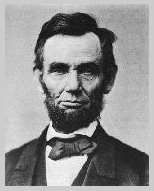

Frederick Douglass's Autobiographies

- "Cotton Harvest, U.S. South, 1850s"; Image Reference BLAKE4, as shown on www.slaveryimages.org, sponsored by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and the University of Virginia Library

- Library of Congress

- Lucky Mojo Curio Company

- New York Public Library Digital Gallery

- Open Library

- Oxford University Press, USA

Historian Jerome Bowers analyzes excerpts from Frederick Douglass's fourth autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom to explore the complicated realities of slavery and the survival of African cultural traditions. Bowers focuses on a story in which Douglass meets Sandy, a conjurer and a slave. Bowers models several historical thinking skills, including:

- (1) close reading to examine the telling of the story;

- (2) drawing on prior knowledge of the transatlantic slave trade, slave life and culture, and Douglass' life;

- (3) corroboration and the meaning of memory by comparing this telling with a version of the story from Douglass's first autobiography and with an example from another slave narrative; and

- (4) placing the story within a larger context of the African customs, the daily life of slaves, and slave agency.

In Frederick Douglass's My Bondage and My Freedom, it's the fourth of his autobiographies, and he elaborates upon a story that he tells in his first autobiography, The Life of Frederick Douglass. And it's where he meets up with Sandy, who he knows from the region as an African conjurer. Sandy is also a slave. He is also a slave who has been sent to the region of the Eastern Shore to be broken. But he is known in the slave community for not giving up the customs and traditions of Africa. And Douglass is a Christian, and the scene is, or the setting is that Douglass has just run away from Covey after being beaten by Covey, and he is fearful of who he hears walking in the woods, and it turns out to be Sandy. And he goes home with Sandy, and he is talking with Sandy about his problem about, "I don't want to be beat any more. I don't want to be put in a situation." And Sandy offers him a root as a talisman, he offers him some herbs from the woods, and it's a real symbol to Douglass of traditional African customs of "something from the earth gives you power." And Sandy encourages Douglass to put it in his pocket and assures him that when he goes back to Covey that Covey won't beat him, or if he does he will have the power to overcome Covey, and it works.

Or at least Douglass questions if it works because when he does go back, Covey is not successful in his second attempt to beat Douglass, and Douglass really struggles then with the confrontation of something African, traditional tribal—prevailed over his traditional, his accepted views of Christianity, and that's a real personal conflict for him.

Well, in his first autobiography, The Life of Frederick Douglass, which is probably the most commonly read, it's barely mentioned in passing. It's barely mentioned. He doesn't go into any kind of details about his own personal struggles with the talisman, about how the fact that he had it in his pocket challenges his own Christian beliefs. So he's thinking a little bit more later in life about who Sandy was, what Sandy represented on the Eastern Shore, how dramatically unique Sandy was from all the other slaves that Douglass encountered. Douglass was almost surprised later in life that the extent to which there could be one person who was still so African.

I think it's a great source to start inquiring about "to what extent have African customs survived the middle passage and the horrors of slavery?" I think the conversation is a natural one to have in the early years of slavery, obviously, but by the time Douglass comes around, slavery is already, the transatlantic slavery has already been cut off.

Slaves are not seen as imported any more, but yet it's a testament to the extent to which African customs and traditions and culture survives the institution, the trade, the trafficking, and the attempts, quite literally, to beat the Africans into submission, into slavery. So, it's a good document for asking those kinds of questions about how does this survive? What does its survival mean? What happens when an African American is confronted with African customs that they have rejected? That's a real internal personal struggle for Frederick Douglass, and it tells us a little bit about the character of the community in which African Americans are operating, that there is no one set definition of what slavery was, who was a slave, how did slaves live their lives, and all the facets that go into creating the African American community.

So, I really ask my students to kind of probe it on that particular level and the questions that come out of that document that lead them to discover a new sense and a new understanding of African Americans.

I usually use it with John Hope Franklin's book, In Search of the Promised Land, which is the story of a female slave who's owned by a Virginian but who lives in Nashville. So, she's allowed to live and exist almost as a free black woman with these tenuous connections to slavery, and it really shows in her life then, the kinds of things that can happen in those complex situations. Douglass's life is also very complex, and so I ask the students to think about this little story, this little snippet, in the larger story of his life.

Well, I hope that they'll try to find out the extent to which slaves were, in fact, either dominated by their master and not dominated by their master. Where are the margins within which slaves can control their own lives? I hope that they'll question their monolithic understanding of slavery because it seems to me that a lot of students come with such an understanding that all slaves lived on a large plantation, all slaves picked cotton, all male slaves were in the field, all female slaves were in the house. It's not the kind of story that gives us any kind of agency among the slaves. So, I really want them to examine that.

It's very important for them to read excerpts about the same event across the four different autobiographies of Douglass.

How did he change in the course of his life? Why did he expand upon the story in one of the narratives but not in the other narratives? Is it something he remembered? Is it something that gained greater importance as he went on in his life?

Those are the kinds of questions that you can ask of an individual, and we always need to get past, especially in slavery, we always need to get past the sense that we're looking for consistency and that individuals are not consistent, and we shouldn't expect that of our historical figures. Here's a slave who was taught to read against the law, and it's done openly. Here's a slave who passes through many masters; again, not the perception most students have of slaves. Here's a slave who does the unthinkable. He confronts a slave breaker. And so in that sense it gives them the hero story, but it also, it's building from a story about which they already think they know something, and I think that's real important that we start with things that they think they know and that they can then learn that there's more to that.