The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum: Personalizing History

Christina Chavarria, of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM)'s Education Division, introduces teachers to the museum. She highlights the importance of using individual stories and specific artifacts to make history live for students.

Christina Chavarria: So just kind of look around. What feeling is evoked? Is there anything that might remind you of something? Or maybe nothing at all. Visitor 1: We were just taking [about] the stairs. Almost as if you can be kind of spread out, and then as you go up closer you have to bunch together to file in. I've never seen stairs that do that, it's weird. Christina Chavarria: Okay, that's true. And when you mention that I think of also the train tracks and how they're kind of elongated and they fade and they seem to become more narrow the further away they become. Anybody else have any thoughts about the architecture, the building? Visitor 2: I think it's overwhelming. It makes you feel small. Christina Chavarria: That's very true. That's a very good point. Because, like I said, going back to the importance of the individual in this history, one of the things that we do with teachers is that we really encourage that you translate statistics into people, that instead of focusing solely on the millions of victims or the thousands who may have died in one place, you take those individual stories and you pull them out using primary resources. Christina Chavarria: What the purpose of these cards do, especially in a teaching standpoint, is, again, they focus on the individual. How many of you have somebody who is not Jewish? Anybody have somebody who is not Jewish? Okay, who? Visitor 3: I have Lucian Belie Brunell. He's born to Catholic parents, he's a priest. Christina Chavarria: Okay, we have a priest. Anybody else have somebody who is not Jewish, somebody who is Roma? Disabled? Okay, how about does somebody have—how many of you have somebody from Poland? Germany? Austria? Italy? France? Denmark? The Netherlands? Greece? Yugoslavia? Okay, any other place that I did not mention? Visitor 4: Romania. Visitor 5: Lithuania. Visitor 6: Hungary. Visitor 7: Czechoslovakia. Christina Chavarria: So another purpose of these is for us to see the range of geography. That this did not happen solely in Germany, even though it began there. This did not happen only in Poland. That it spread geographically. It spread all the way into Northern Africa and other parts of the world were impacted, even if they were not occupied by Nazi Germany. Christina Chavarria: Look at the monitor. TV Documentary: "—called in by radio, said that we have come across something and we're not sure what it is. It's a big prison of some kind, and there are people running all over—sick, dying, starved people. You can't imagine it, things like that don't happen." Christina Chavarria: So as we go through, as I mentioned downstairs, I'm not going to point out everything to you, but there are certain elements that I want to point out because we will talk about them in the afternoon. This, in particular, I think is very striking for us as teachers, as social studies teachers, as teachers in the United States. You notice at the top it says, "Americans encounter the camp." We don't use the word in this picture—we don't use the word "liberation." Why not? You couldn't just walk out and go home, first of all. And liberation has that connotation of being free, and yet the obstacles that lay ahead for those who did survive will be so vast—the obstacles, the challenges, for the Allied forces and relief workers who come into the camps. So, we chose that word "encounter." And this was not, as we know now, this was not the first that we knew of the camps. It was the first maybe that we had seen of the camps with our own eyes, but we will see that. When you look at this history again we define it the years 1933–1945. Christina Chavarria: Where you all came in, we call that the Eisenhower Plaza. This quote up here that's on the side of the building, of the museum structure. Because if you look at it, I think this is an excellent quote to use with students because it takes us back to that theme of anti-Semitism and that theme today of Holocaust denial.

Christina Chavarria: I think as teachers here in the United States, the issue of race science, which was very popular in the United States, it was not only in Nazi Germany. If you look at your own states—if each individual state looks at its history—you can look and see the laws that were on the books regarding sterilization, regarding who could marry whom. So, again, looking at U.S. history, especially in the latter part of the 19th century and the eugenics movement and how this became so popular. And the whole notion of race, the definition of race, and categorizing people. This is very, very relevant. Christina Chavarria: What are the questions that your students ask when you're teaching this? How many of you have taught about the Holocaust? Visitor 1: They want to know why; they want to know how could this have started? They want to know, you know, why is Hitler so anti-Jewish, anti-Semitic? They want to know the root of it all. Visitor 2: They want to know, too, why they willingly were prisoners. You know, 7th grade, why, I would have not done this— Christina Chavarria: I would have fought back, right? And they did, that's a very good issue to bring up. They did, and we have to teach about resistance. One of the questions related to that is: Why didn’t they just leave? Why didn't they just pack up and go somewhere else? Well, again, the complexities of this history—don't avoid those questions when they ask you. Why didn't, why couldn't they just pack up and leave? We look at the Évian Conference, which is where we look at the failure of other nations to respond to the growing crisis in Europe. And this symbolizes that, this political cartoon. This appeared in the New York Times, July 3, 1938, just before the Évian Conference was to begin. So we can take this image and we can deconstruct this, and what do we see happening here? Visitor 3: The guy's at a stop sign with no place to go. Christina Chavarria: The stop sign is on what? Multiple Visitors: A swastika. Christina Chavarria: Every point, every direction ends with that halt—you can't, you can't go. And who is this person? Visitor 4: Non-Aryan. Christina Chavarria: Non-Aryan, presumably Jewish—the kippah. And what's on the horizon? The Évian Conference invited nations to attend to discuss the growing refugee problem. So 32 countries send representatives to this conference, but, yet, they're also told we're not going to ask you to take any more people in. So the conference was basically a failure before it even began because only one country stepped forward and said, "We're willing to take in more refugees than what we have on our quotas, listed as our quotas." Does anybody know what that country was, what that one country was? It's right down here. The Dominican Republic. This also revealed a lot of anti-Semitic thought from leaders of other nations. Some countries said, "We don't have a Jewish problem and we don't want to import one." Some said, "We're going through our own issues." And that's very true, because we've got to contextualize this from what happened in the 1920s, what happened in 1929, the economic—the Depression as well. But, yet, we also have to factor in anti-Semitic sentiments because who are these refugees? Well, they're mostly Jewish, they might take our jobs, they might take—we don't have money to support them.

Christina Chavarria: Looking at the whole idea of refuge, and the search for refuge, where do you go when nations have closed their doors to you? Where do you go? What kind of documentation do you need to get out of Germany? What documents do you need? What kind of money do you need to emigrate? These are all issues that you have to bring up with your students so that they understand why they were trapped in Europe. Christina Chavarria: This chart that we see here, this is the forced immigration chart that Adolf Eichmann's office produced to show how it was able to expel, within three years, most of Vienna's Jewish population. After the Anschluss, after Kristallnacht, this is when Jews in the occupied territories—Germany, Austria, parts of Czechoslovak—after Kristallnacht, they realized that they can no longer stay. Life is just not bearable any more; in fact it's dangerous now. In many cases, many of them actually bought visas to get out. Some countries made money, some diplomats made money selling fraudulent visas that turned out to be no good. And that is what happened with the voyage of the St. Louis. Out of the 937 passengers who were on the boat, almost—I think all but maybe six to eight of them were Jewish. They needed to get out, and Cuba was the destination of this ship, the St. Louis. It was owned by the Hamburg line, Hamburg America. They had acquired visas to go to Cuba, where they were planning to stay until their numbers came up to come to the United States. But before they reached Cuba, their visas were rescinded; in fact, many of them were fraudulent, only about 28 of them were actually valid. So when they got to Havana, they were not allowed to dock. Only those who had valid visas, which was just a miniscule number out of the over 900 those people were allowed to stay, and the rest could not get off the boat.

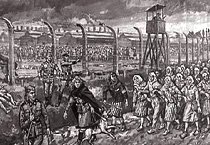

Christina Chavarria: Here you see newspapers from some of the major cities across the country reporting on the front page certain events that were taking place in Nazi Germany between 1933 and 1939. Right here, for example, the Dallas Morning News: Kristallnacht, November 1938, front page. This was not a secret. Christina Chavarria: This is called "The Tower of Faces." This is one thing I want to point out to you because—just take a couple minutes to look around at the pictures. This represents one shtetl, one Jewish community, in Lithuania. The little girl right here is Professor Yaffa Eliach, she lives in New York. She went back to this shtetl, Eishyshok, and she gathered the 10,000 photos, many of which you see here, and which we have online. Again, what this does, we look at the individual; we look at the victim not as a "victim," but as a vibrant human being. I think anything we teach, whether it's the Holocaust or any other topic that we're looking at in history, we have to look at the individuals. Christina Chavarria: This milk can is one of three milk cans that was used to bury documents and chronicles of life in the Warsaw Ghetto. And in 1950, two of the milk cans were excavated as well as the other metal boxes. Within them they found a very rich documentation of what life in the ghetto was like. Christina Chavarria: Actual barracks that are on loan to us from Poland, they are not replicas. Right over here we have a large-scale model of the process of going through the selection, going to the gas chambers, because we don't have any photos of the actual gassing, of course. Christina Chavarria: The diary, the quote, and the armband, take a look at that. The diary is the first diary that was donated to us by an American in captivity. Most of the diaries that we see they were written when they were in hiding or before they had to leave, but he was able to keep his diary while he was in the camp. It's also striking because Anthony Acevedo—he's not Jewish, in fact he's the son of Mexican immigrants. He is—we consider him to be a survivor, because of the fact that he went through a sub-camp of Buchenwald. Christina Chavarria: This is one of over a thousand citizenship papers that was found in somebody's attic in Switzerland. In a suitcase were these documents, these citizenship papers, issued by El Salvador that stated that the individuals who were named in the documents, whose pictures appeared on the documents were citizens of El Salvador, when in reality they were not—most of them were Hungarian Jews. This is 1944, Hungary is invaded in the spring of 1944 by Germany, and out of about 500,000 Hungarian Jews, over 430,000 died at Auschwitz in a very short period of time.