Namesake of a Peacekeeper

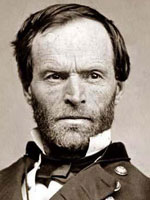

How did General William Tecumseh Sherman get his middle name? It seems unusual for a 19th-century white family to name a son after an American Indian leader who fought against the United States.

Prior to the War of 1812, the Shawnee chief Tecumseh tried with his brother Tenskwatawa, a religious leader known as the Prophet, to revivify a confederacy of Indian peoples and rebuild it strong enough to halt the rapid expansion into their lands of American settlers, prevent additional lands from being sold to whites, and preserve Indian cultures from European influence. A number of such confederacies had been formed previously but had failed to hold together. Tecumseh ultimately allied with the British in their war against the U.S. and died in battle on October 5, 1813 at the Thames River in present-day Kent County, Ontario, fighting American soldiers who had invaded Canada. His confederation was the final one that posed a serious threat to American westward expansion.

Tecumseh was highly respected by many of the white men who fought with him and against him. Tecumseh's ally, British general Isaac Brock, stated in 1812 that Tecumseh "has the admiration of everyone who conversed with him." Major John Richardson, who became Canada's first novelist, called him "a savage such as civilization herself might not blush to acknowledge as her child." Michigan Territory Governor Lewis Cass, who led militia troops against Tecumseh, praised him as "remarkable in the highest degree" and characterized his oratory as "the utterance of a great mind roused by the strongest motives of which human nature is susceptible; and developing a power and a labor of reason, which commanded the admiration of the civilized, as justly as the confidence and pride of the savage." In journalistic accounts, Tecumseh was represented as an Indian Napoleon, Hannibal, and Alexander. Towns in Michigan, Nebraska, Kansas, Missouri, Indiana, Alabama, Oklahoma, and Ontario today bear his name.

Historians have attempted to account for the great admiration that whites had for Tecumseh. R. David Edmunds suggested that his "attempts at political and military unification seemed logical to both the British and the Americans, for it was what they would have done in his place." In addition, Edmunds proposed, "More than any other prominent Indian, Tecumseh exemplified the European or American concept of the 'noble savage,'" pointing specifically to his "kindness toward prisoners [that] particularly appealed to Americans." John Sugden listed qualities that Americans admired in Tecumseh: "courage, fortitude, ambition, generosity, humanity, eloquence, military skill, leadership . . . Above all, patriotism and a love of liberty." Richard White has noted the ironic nature of this admiration: "Tecumseh, the paradoxical nativist who had resisted the Americans, became the Indian who was virtually white."

Charles R. Sherman, the father of the future general, who settled in the Ohio Valley in 1811 and later became an Ohio State Supreme Court justice, was among the many admirers of Tecumseh. Lancaster, Ohio, where the general was born in 1820, is less than 40 miles northeast from the old Shawnee town of Chillicothe—just north of the present-day town of the same name— where historians believe that Tecumseh likely had been born some 55 years earlier. The Rev. P. C. Headley, in an 1865 biography of Sherman, one of at least five books about the general published since his military campaign of the previous year, quoted an unidentified person claiming to be from the area of the general's birthplace, who had written to Headley that Tecumseh "was for a long time kept in rather fond remembrance in this immediate vicinity, by those who were engaged in that conflict . . . because they knew that several times he prevented the shedding of innocent blood." The writer went on to relate that the desire of Sherman's father "to have one son educated for military life, led him to choose Tecumseh for the boy, he being born not long after the death of that chieftain."

Some 20 years later, Sherman himself, in the second edition of his memoirs—he had neglected to discuss his early life in the first edition— wrote that the War of 1812 "caused great alarm and distress in all Ohio." He stated, "Nearly every man had to be somewhat of a soldier, but I think my father was only a commissary; still, he seems to have caught a fancy for the great chief of the Shawnees, 'Tecumseh.'" When Sherman's older brother James was born, the general related, his father "insisted on engrafting the Indian name 'Tecumseh' on the usual family list." Sherman's mother, who had named her first son after a brother of hers, prevailed, however, in her desire to name her second son after a second brother of hers. By the time of his own birth, Sherman continued, "mother having no more brothers, my father succeeded in his original purpose, and named me William Tecumseh." As a boy, Sherman was called "Cump" by family members.

In 1872, William J. Reese, Sherman's brother-in-law, wrote that the choice of an Indian name did cause some consternation in the community. "Judge Sherman was remonstrated with, half in play and half in earnest, against perpetuating in his family this savage Indian name," Reese remembered. "He only replied, but it was with seriousness, 'Tecumseh was a great warrior' and the affair of the name was settled."

The oft-repeated use of the term "savage" in describing Tecumseh and Indians in general points to deeply rooted ideological ways of understanding cultural difference that whites at the time had even with respect to individuals such as Tecumseh, whom they clearly admired. Historian Robert F. Berkhofer has traced "persisting fundamental images and themes" of European understandings of Indians, noting the practice of "conceiving of Indians in terms of their deficiencies according to White ideals rather than in terms of their own various cultures." Whites, Berkhofer contended, often used "counterimages of themselves to describe Indians and the counterimages of Indians to describe themselves." The strength of such persistent dichotomies between savage Indians and civilized whites becomes even more noticeable in light of the irony that in the aftermath of the battle during which Tecumseh died, his corpse was scalped and pieces of skin were removed by American soldiers for souvenir strips and razor strops. Sudgen has written that "Henry Clay was said to have exhibited one in Washington the following winter."

Robert F. Berkhofer, Jr., The White Man's Indian: Images of the American Indian from Columbus to the Present. New York: Knopf, 1978.

Benjamin Drake, Life of Tecumseh, and of His Brother the Prophet; with a Historical Sketch of the Shawanoe Indians. Cincinnati: E. Morgan, 1841; reprint: New York: Arno Press & New York Times, 1969.

R. David Edmunds, Tecumseh and the Quest for Indian Leadership. Edited by Oscar Handlin. Boston: Little, Brown, 1984.

Bill Gilbert, God Gave Us This Country: Tekamthi and the First American Civil War. New York: Atheneum, 1989.

P. C. Headley, Life and Military Career of Major-General William Tecumseh Sherman. New York: William H. Appleton, 1865.

William J. Reese, quoted in Lee Kennett, Sherman: A Soldier's Life. New York: HarperCollins, 2001.

William T. Sherman, Memoirs of General William T. Sherman. 2d Edition, revised and corrected. New York, D. A. Appleton, 1886.

John Sugden, Tecumseh: A Life. New York: Henry Holt, 1997.

Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 16501815. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1991.