So it's written by James Leander Cathcart, who was the U.S. Consul in Tripoli, to the Secretary of State in May 1800, and he's writing to explain that the Bashaw, or the leader of Tripoli, has become very unhappy with treaty arrangements. Americans were trying to trade in the Mediterranean, particularly with European countries, so they were trading with Europe, Bordeaux and Lisbon and ports like that, but the Barbary pirates would—basically they had a protection racket. So if you didn't pay them some sort of tribute or some sort of money, they would capture your ship, so it would make it very difficult for you to trade. And Americans really needed that type of trade to go on.

So Tripoli—Cathcart, rather, is in Tripoli trying to arrange those—smooth things over with the Tripolitan Bashaw. And the Bashaw has become aware that Algiers is getting paid more than he's getting paid, and this is making him unhappy. What he probably also knew is that Americans were three years behind in their payments to Algiers, so even though the treaty looks better on paper for Algiers, Americans weren't able to make those payments because they were just so short of cash. So the Bashaw had apparently informed Cathcart that unless he received presents in addition to whatever tribute payments had been arranged, he was going to declare war.

And Cathcart is communicating that information to the Secretary of State and indicating that they can—They have a few options. The President is supposed to respond. The Bashaw expects him to respond—not Congress, not Secretary of State, but the President, so as long as the President responds in a reasonable amount of time, they can take a little bit of time for that response to come. Cathcart also indicates that if they're going to make payments, if they're going to make a present to the Bashaw, that that will probably buy another year, and after that time the Bashaw will will probably once again become unhappy and demand some sort of payment or presents.

Cathcart is also of the opinion, in this letter, that if the Americans were able to send ships over, it would protect their commerce. So he, I think, in another letter, suggests a couple of ships would do. If they were able to send four ships, it would be enough to take care of the problem, and the force would overwhelm the need to send presents.

Cathcart also says or gives some of the details of other arrangements. For instance, the Danes and the Swedes are also making these protection payments, and what I found particularly interesting is he indicates how much those payments are—so he says they're paying 1500 dollars every three years which seems like quite a bit of money. It was quite a bit of money then.

And you can see the trouble that Americans are having. They don't have a lot of money in the federal government, even though they're at least operating under the Constitution instead of the Articles of Confederation. They can't pay Algiers, let alone Tripoli. They need desperately to trade in the Mediterranean, but they're not able to either protect their trade or make the payments that they need to make.

It is difficult for students, I think, to understand the language, and I find if you can have students read it out loud, that they can often make sense of it. And it is meant to be a public document, so it's being sent to the Secretary of State, but Cathcart is well aware that this is going to be a document that's going to circulate. It might be published in part in the newspaper, it might be something that's going to end up in collections for the government, it might be in Congress. So he's definitely writing in a way that he thinks will look good for other people to read, which can be difficult for us to interpret.

He's also using terms that may be unfamiliar, like the Imperials, the Danes. Ragusians, which was a very small trading state on the Dalmatian coast. And those powers that he's listing there are not very strong powers. So the British, the French, had very strong navies, but these people do not, and they're involved in the carrying trade, because they, like the Americans, are neutral states, and there's so much war on the continent at that time period that the neutral states are making a lot of money in the carrying trade—as long as they can pay off the Barbary pirates.

Well, there's actually humongous subtext, and if you're going to do further research, there are two ways I think that you could have students approach this. One is the issue of trade and how trade was carried out at that time period—and increase in violence, as well, between the 1780s and the early 1800s. There's an incredible increase in violence in trade in general. The French Navy, for instance, grows something like 40 or 60 percent, and that's fairly standard. A lot of European and Russian navies—the Algerian navy, for that matter, grows at this time period. There are European powers, including the Neapolitans, who are seizing American ships. One historian estimated that between about 1800 and about 1810, other powers seized about 1,600 American ships all told. And North Africans take 13 of those ships. So the North Africans are the least of our problems in many ways.

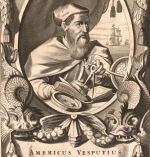

And I think Cathcart, that's the second way you could approach this, Cathcart himself is a really interesting case. He's very concerned about the issue in Tripoli, and he's concerned in a really personal way, because in 1785, as a young man in his early 20s, he was captured by Algerian pirates and he was enslaved in Algiers for 11 years. In 1796, he is finally redeemed, by the United States, with a bunch of other Americans, and returns home and is appointed then to be the Consul in Tripoli.

So he has a really unique insider viewpoint. He knows North African politics. Most Americans don't. You can tell that he's trying to pitch this idea to the Secretary of State, that you might have to make presents or force. And that's really clear, and it's been clear to Europeans since like the 12th century—you're either gong to make these payments or you're going to get a big enough navy to do something about it.

America is kind of in a bind. It doesn't have a lot of money to do either, and Cathcart is trying to convince them, I think, to use force. I think there are two things—one is that he says If we make this payment, it's only going to delay things for about a year. And the other place is where he talks about pretenses. That they're going to attack us no matter what, they're going to come up with excuses no matter what to attack us. So we might as well put a stop to it forever, and the only way to do that is force, and that's what I'm seeing between those lines, where he's talking about pretenses and delaying and it's only going to be a year and then we're going to have to do something else.

Well, I think, in fact, these Tripolitan pirates are privateers. Everybody else's privateers look like pirates to you. And privateers, what that means is that it's a government-arranged, government-sponsored program of piracy. And the Tripolitans were very clear about it. If you make arrangements with them, if you sign a treaty with them, they're not going to capture your ships. If you don't, they will capture your ships.

They know to capture your ships because you're carrying what's called a Mediterranean pass, so if you're trading legitimately, and you're trading legitimate American goods on an American ship, you're going to have one of these Mediterranean passes and Tripolitans are going to board your ship and they're going to check out your pass and see if things are in order, and if things are in order, they won't capture your ship. If things are not in order, if you don't have your pass, if you are not actually a legitimate American ship, you're just claiming to be an American ship, they're going to capture you and they're going to take your goods and they're going to sell your ship and possibly enslave the people that you have on the ship. Every ship that's not convoyed—so sometimes Americans were able to get French or British or Portuguese ships to convoy their ships, so if you don't have the force to keep them from stopping their ship, yes, they're going to stop your ships.

And in part they have that power because in 1785 the Spanish made a treaty with them—the Spanish then stopped keeping them out of going through the Straits of Gibraltar, so they could actually get out into the Atlantic after 1785. You didn't have to come into the Mediterranean, in other words. You could be trading on the coast of Portugal, and they could still stop your ships.

So this is very much an organized state endeavor. The pirates are organized by the state, they're supported by their state, it's part of the taxation system of the money that the state is bringing in, in Tripoli. And the government in Tripoli is telling the privateers which countries are appropriate for them to attack. They really are using terms that indicate they're seeing themselves as more of a navy, so that Morad Raiz that's mentioned, Raiz is their term for captain, so that just means he's a captain in the navy, and this is his job basically. He's told by the state, the Americans aren't paying us enough, we want them to pay us more, you should stop their ships. And if it looks like they have a lot of booty on board, then we need to capture them and make things difficult for the Americans so they will negotiate with us.

They'd sell the ships, they'd sell the goods, sometimes—the Tripolitans are less likely to do this but Algiers, in particular, would enslave the men. By the early 1800s, Tripolitans are less likely to do that. And to be fair, Europeans are doing this as well. I think it's 1790, there's something like 800 Muslims held in Malta, so privateering was going on on both sides, and both sides are calling the other people's navy pirates, and they're all privateers, they're licensed by the state.

Normally I'm a big fan of handing out primary sources and just seeing what they do with it, but, I think in this case, I would want to make sure that we had looked at a map together and seen where these places are, and seen what's on the Mediterranean, and seen maybe the ports, the European ports, so they they could a get sense of how close you have to get to North African ports and how far their ships would range. I think I might also want to talk with them about what people were trading over there, because that's one of the questions you're left with, why are Americans trading with Tripoli? They really aren't trading with Tripoli, but they're taking a whole bunch of flour and wheat over to the European continent, is really what they're trading.

So I might want to set up some of the context. Why are we going there? What's going on once we're getting there? Who are these Tripolitans? Where are they Iocated, so they could get a sense of what was going on. I would ask them to come up with a list of questions from the source, so that we could talk about what was confusing to them or talk about some of the things that they were interested in. And what I would hope would come out of that is that they would ask even more detailed questions about the relationship and how was the government involved, but also the relationship between the United States and Tripoli. Why Tripoli is taking the ships, I think that would be a really interesting question for them to ask.

The other thing I was struck with is that at the very end and at the very beginning of this letter, he talks about how long it takes letters to get back and forth. So I think that raises a lot of issues about doing government business, if it takes two and three months to get letters back. And of course Cathcart is probably sending multiple copies of the same letter by various ships, hoping that one of them will make it, because those ships are very likely to be captured by Algerians, by the French, by the English, and never make it home

And in fact, he's kicked out of Tripoli and Tripoli declares war on the United States, and the Americans don't know for another month or so after that war has been declared because he can't get the information back soon enough. So meanwhile, America does send a couple of ships over, and the ships are charged with either making arrangements or attacking. So they're sent with some money, and said if you can smooth things over, if you can make things work out alright, that's okay, but if you have to use force, use force. They get to Gibraltar and they find that war has been declared. And what happens after that is Americans have—I think it's five ships that are sent as part of that flotilla, and they blockade the Tripolitan port. Unfortunately, they blockade it ineffectively because they're only five ships. And what they find is that the Barbary States in general work together. So they're blockading Tripoli, but Algerian ships take Tripoli goods, Tripoli passengers, and they're able to get into the harbor of Tripoli because we're not officially at war with Algiers. Tunis does the same thing, so they load up goods on their ships and they're able to get into the harbor and America can't really do anything about that.

Incidentally, at the same time, one of the states that's often part of that Barbary States configuration, Morocco, looks like they're going to declare war, so some of those ships are sent down to Morocco to protect American shipping, basically, past Morocco, which is on the Atlantic and much more able to take American ships.

And basically, between 1800 and 1803, we try to blockade Tripoli, to no effect, because the Barbary States are all working together, because we don't have enough ships to blockade that port, and so there's sort of a standstill. There's a series of actions but nothing incredibly exciting until 1803, when the Philadelphia is chasing a Tripolitan ship into the harbor of Tripoli, and apparently, the captain and his navigator—David Porter is the navigator, Captain William Bambridge is the captain—apparently, they don't have a very good map of the Tripolitan harbor, and they run the ship aground on a reef that the Tripolitan ship would have had knowledge of.

It's the largest ship in the Navy at that time, and William Bambridge tries to save the ship by throwing everything he can find off the ship. So they're unloading cannon, they're throwing it into the water, he's trying to get the ship to lift, so it will free from the reef. But he's not able to free the ship. So the Tripolitans capture the ship, they capture the crew of about 307 men, they take them into the city of Tripoli and put them in a prison.

And then they use the American men to refit their own warship, because the next day, the Tripolitans are able to free that ship from the reef and bring the ship into their harbor. So that's a very difficult situation for the Americans. They have—the Tripolitans have managed to capture the largest ship in the Navy, they've got 307 hostages to work with. In 1805 we sign a treaty with Tripoli, and it's really through that treaty diplomatically that things are solved.

William Eaton, who is a consul, or an American diplomat, in Tunis, is extremely aggravated that we're paying money to pirates, so he pitches a plan to the President that we should take land forces into Tripoli—so we have the Navy working, we'll have Marines in Tripoli, and we'll be able to take the country. And William Eaton convinces the Bashaw's—the leader of Tripoli's—brother, Hamet, to work with us. Eaton and about 200 marines and several thousand Tripolitans, Berbers, all kinds of people who flock to the that banner of Hamet do in fact have this long dramatic march through Tripoli and are able to stake out the city of Derna. And they're holding that city, and William Eaton believes that they're holding it successfully, but there are thousands and thousands of Tripolitans surrounding them, and the Bashaw is just sending some of his professional soldiers down there, so it looks very bad for him.

Meanwhile, Tobias Lear has been sent over to make final negotiations, and he agrees to pay 60,000 dollars to free those American soldiers who have been captured, including William Bambridge, and signs a favored nation treaty with the Bashaw that includes, basically, presents, which are tribute payments, but they call them presents. So, from an American point of view, it looks like he's arranged a treaty that does not include tribute, but from the Bashaw's point of view, he expects those presents, and to him it's tribute.