September 17, 1787, was a seminal day for America.

Earlier that year in May, spurred by inadequacies in the Articles of Confederation and the need for a strong centralized government, 55 delegates representing 12 states met in Philadelphia to "take in to consideration the situation of the United States, to devise such further provisions as shall appear to them necessary to render the constitution of the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union."

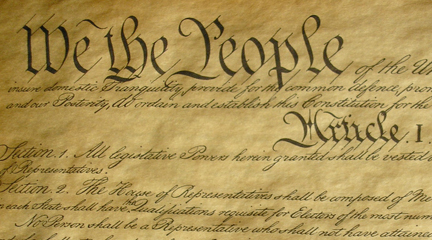

In secret proceedings, the delegates argued and debated throughout the summer about the duties, responsibilities, form, and distribution of power in the new government. Then, on September 17, 39 of the delegates signed a four-page document— a Constitution consisting of a Preamble and seven articles proposing the infrastructure of American government. Then the ratification process began.

Constitution and Citizenship Day, initiated in 2005 and observed on September 17, commemorates the event and mandates that each educational institution receiving Federal funds conduct an educational program on the Constitution on that day. Background papers, interactive lesson plans, and supporting materials abound for classroom use. We mention only a few below.

Department of Education

At the Department of Education, the Teaching American History Team at the Office of Innovation lists several essential resources from Federal institutions, including FREE, the Department of Education's own internet library highlighting 28 diverse teaching resources on the Constitution.

The Teaching American History team also annotates the varied resources of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) including high resolution scans of the original signed Constitution with transcripts and factual support.

From the National Constitution Center to to iTunes

The National Constitution Center in Philadelphia describes its facilities as the only museum devoted to the U.S. Constitution and the story of We, the people. But for those too far away to visit, the museum offers extensive materials for educators, including the Interactive Constitution, enabling keyword and topical exploration of the Constitution as well as analysis of landmark Supreme Court decisions interpreting the Constitution.

Have you attended iTunes University? The National Constitution Center is among the organizations presenting free audio files related to all aspects of the document and its meaning. Listen online or download We the People Stories where experts present ideas on everything from today's relevance of the Constitution, to talks about George Washington, the relationship of the Constitution to the Olympics, and presidential elections— few topical stones are left unturned. (This series is also available via podcasts.)

Do you know which Article of the Constitution created Congress or what the powers of Congress actually are? In its Capitol Classroom, the U.S. Capitol Historical Society challenges visitors to take a quiz to test Constitutional knowledge. Tiered levels offer questions appropriate to 811-year-olds through the Constitutional Scholar level.

Among its many resources, the Bill of Rights Institute offers a variety of educational resources free of charge. Weekly eLessons provide 20-minute discussion guides for middle and high school history and government teachers. Educating the Next Generation, a blog, highlights classroom applications and current resources.

The Library of Congress provides a consolidated listing of resources for teachers, including primary sources, lesson plans, Stories for Kids from America's Library, and links to American Memory Collections.

Discussions, Multimedia, and Lesson Plans

The National Endowment for the Humanities educational site, EdSITEment, consolidates comprehensive resources for teaching about the Constitution, amendments, and the people who made it happen. From lesson plans (K12) to webography, from biographies and bibliography to teaching with art in the classroom, EdSITEment's presentation of resources offers a wealth of materials to deepen our understanding and approaches to teaching about this document and its meaning.

EdSITEment's inclusion of materials for elementary and middle school students is particularly valuable. A few of those resources are highlighted:

The Preamble to the Constitution: How Do You Make a More Perfect Union? helps students, grades 35, understand the purpose of the Constitution and the values and principles explicated in the Preamble.

The Constitutional Convention: What the Founding Fathers Said, designed for 68th graders, looks at transcriptions of debates of the Founding Fathers to learn how differences were resolved.

The Constitutional Convention: Four Founding Fathers You May Never Have Met is designed for 68th graders and introduces lesser-known key players in the development of the Constitution.

A roundtable discussion published in Common-place, the interactive, online journal, includes eight paired essays in which historians, political scientists, journalists, and lawyers examined the uses and abuses of the Constitution in contemporary American political affairs. Jill Lepore, Jack Rakove, and Linda Kerber are among the discussants.

The Social Studies and History resources of Annenberg Media: Learner.org include the Emmy-Award-winning series The Constitution: That Delicate Balance . In this series of free, video-on-demand presentations designed for high school and above, key political, legal, and media professionals engage in spontaneous and heated debates on controversial issues such as campaign spending, the right to die, school prayer, and immigration reform. The resources emphasize the impact of the Constitution on history and current affairs. The Annenberg Newsletter highlights additional resources.

Landmark Supreme Court Cases provides teachers with a full range of resources and activities to support the teaching of the impact of cases such as Marbury vs Madison, Plessy vs Ferguson, and Brown vs. Board of Education. Background summaries of individual cases and questions for three different reading levels are graded from the highest to those appropriate for ESOL students. Resources include many case-specific short activities and in-depth lessons that can be completed with students.