Thomas Jefferson and Executive Power

"In this seminar, we will attempt to lay out Jefferson's understanding of executive power, trace its consequences for American political development, and discern its contribution to republican theory."

"In this seminar, we will attempt to lay out Jefferson's understanding of executive power, trace its consequences for American political development, and discern its contribution to republican theory."

"This seminar gives special emphasis to selected Jefferson manuscripts, offering participants an intensive exploration of primary sources—the building blocks of historical study. Monticello itself is the site of several study tours. Lecture and discussion topics include Jefferson and the West; archaeology at Monticello; African Americans at Monticello; the architecture of Monticello; Jefferson’s empire; the Louisiana Purchase; and Jefferson and the Constitution."

According to the Monticello website, this fellowship "provides individual teachers an opportunity to research and study at Monticello and the Jefferson Library. It will allow teachers to work on Jefferson-specific projects such as lesson plans, curricular units, resource packets, or syllabus outlines that will enhance their classroom teaching. Fellowship recipients will spend two weeks in independent research and consultation with Monticello scholars on projects that relate directly to Thomas Jefferson and that will enhance their classroom presentations."

"Fellowships will be awarded to qualified elementary and secondary teachers who are employed full-time in the classroom."

I have heard that Spain was not happy about the Corps of Discovery expedition led by Lewis and Clark and that a group of soldiers and Comanches was twice sent out to stop them. Can you give me more information about these efforts including who led the detachment of soldiers, or point me in the direction of a website or book that would have this information?

The Spanish believed that any American expedition into the Louisiana Territory would lead to attempts to conquer Spanish territories to the west and south. President Jefferson, in fact, did believe that the United States would eventually expand across the continent out to the Pacific Ocean, and he had long planned in secret for at least one expedition of explorers to be sent out to the far west, even before he acted on the fortuitous opportunity to purchase the Louisiana Territory from France (which had just reacquired it from the King of Spain).

Merriwether Lewis and William Clark set out into the Louisiana Territory just as it was being officially turned over to the United States in early 1804 (the Purchase had been made in 1803). But the borders of the territory had not yet been well determined and Spanish authorities in America had good reason to suspect that the expedition would intrude into tenuously held Spanish territory. They also suspected, rightly, that the expedition was not just a matter of satisfying Jefferson’s scientific curiosity about the region, but that the expedition would also attempt to turn the Indian tribes they encountered against the Spanish and make them friendly toward the United States for both military and trading purposes.

On March 5, 1804, Sebastiàn Calvo de la Puerta y O’Farril, marqués de Casa Calvo, the former Spanish governor of Louisiana, who was remaining in New Orleans to serve on the boundary commission that was to demarcate the Louisiana Territory, sent a letter to Nemesio Salcedo, Commandant General of the Interior Provinces in Chihuahua, warning him about the expedition and instructing Salcedo to send out a force to intercept and arrest the explorers. Delays followed, but on May 3, Salcedo ordered the Governor of New Mexico, Fernando de Chacón, to dispatch a force to find Lewis and Clark, who had already begun their journey four months before. Chacón sent out a party headed by two frontiersmen, Pedro Vial and José Jarvet, who led a force of 52 soldiers, Spanish settlers, and Indians, from Santa Fe on August 1. By September 3, they reached a large Pawnee settlement on the Platte River in central Nebraska. There, they assiduously distributed presents to the local chiefs and learned that American “traders” had lately been in the area. In fact, Lewis and Clark’s expedition had passed that way, but by the time that Vial and Jarvet reached the Platte, the Corps of Discovery was already far to the north, poling up the Missouri. Unable to get a clear idea of where Lewis and Clark were (actually, they were only about 100 miles away), Vial and Jarvet returned to New Mexico, arriving in Santa Fe on November 5. Salcedo ordered Vial and Jarvet to conduct another attempt to counter Lewis and Clark in October 1805. They were given orders to negotiate with the Indians with the aim of forging close alliances with them so that the tribes would intercept Lewis and Clark upon their return journey. Vial and Jarvet set out from Santa Fe with about 100 men, soldiers, traders, and militia, but when they reached the north bank of the Arkansas River on November 6, they were attacked by a force of Pawnee, and had to return to Santa Fe. In April 1806, Vial led a third force, this time numbering about 300, on a similar mission to make Indian allies among the Pawnee, but his men soon turned against him and deserted, and he returned again to Santa Fe.

In June, Salcedo dispatched another force from Santa Fe under the command of Lieutenant Facundo Melgares. Melgares had about 600 men under his command composed of 105 soldiers, 400 militiamen, and about 100 Comanches, all accompanied by nearly 2000 horses and mules. It was the largest military force that Spanish authorities ever sent out into the Plains. Melgares’ mission was to impress the wavering Indians who had been allied to Spain until then and to repel or apprehend any American exploring expeditions it could find, including the one under Lewis and Clark. Hampered by the Pawnees’ suspicions and opposition, Melgares’ formidable but unwieldy force did not succeed in reaching the Missouri River, where it might have encamped and encountered Lewis and Clark on their return trip. The Corps of Discovery reached St. Louis on September 23, 1806, and Melgares and his men returned to Santa Fe the following month.

While Lt. Megares was on his mission, three American expeditions in the West were exploring and probing along the borders with Spanish territories. Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery was just one of them. Another party was being led by U.S. Army Lieutenant Zebulon Montgomery Pike and was meant to explore the Rocky Mountains in the headwaters of the Arkansas River. (Pike had just completed an expedition from August 1805 to April 1806 up the Mississippi River from St. Louis to Minnesota to seek out the source of the Mississippi River.) His second expedition, of about 15 men, set out from near St. Louis on July 15, 1806. They journeyed through present-day Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, and Colorado, and then south, close to Santa Fe. A Spanish force of about 100 dragoons and militiamen, sent out from Santa Fe and under the command of Lieutenant Ignatio Saltelo, apprehended them on February 27, 1807, and turned them over to Governor Salcedo, who questioned them and had them sent to Chihuahua, from where they were eventually repatriated to the United States in July. The Spanish government charged the American government with responsibility for Pike’s actions, and claimed damages of about $22,000, for the cost of searching for Pike. The Spanish claims were not resolved until 1819, as part of the Adams-Onís Treaty, which demarcated borders between the territories of the United States and Spanish possessions in North America. Another American expedition had been sent out in April 1806 to explore the headwaters of the Red River, led by U.S. Army Captain Richard Sparks, and naturalists Thomas Freeman and Peter Custis. (Yet another small expedition, under William Dunbar and George Hunter had earlier been sent into areas along the Ouachita River in present-day Arkansas and Louisiana and had returned at the beginning of 1805.) The small Sparks expedition of 24 men traveled 600 miles up the Red River and was intercepted by a force of Spanish troops under the command of Captain Francisco Viana from the Spanish garrison at Nacogdoches on July 28, 1806. The Americans were ordered to return back down the river, which they did.

Although Jefferson believed that the United States would eventually expand out to the Pacific, pushing Spain out of the picture, he did not wish to force a confrontation, believing that it would be better for the long-term interests of the U.S. if the Spanish presence in the western territories prevented Britain from advancing south from central and western Canada. Jefferson therefore made preparations for the Lewis and Clark Expedition in secret in order not to provoke Spain. Spain knew about the planning for the expedition, however, in part because Brig. General James Wilkinson, the senior officer of the United States Army, had informed the Spanish about it in detail. He had, in fact, secretly renounced his loyalty to the United States as far back as 1787, and, in a “memorial” he had signed in order to be awarded a trading monopoly by the Spanish along the Mississippi River, had declared that he would dedicate his life to the “good of [Spain] and aggrandizement of the Spanish Monarchy.” In truth, Wilkinson spent his entire career dedicated to his own aggrandizement, plotting conspiracies and counter-conspiracies, playing off one side against another.

Along with the U.S. governor of (southern) Louisiana, William Claiborne, Wilkinson represented the United States at the ceremonies in St. Louis in March 1804 that officially transferred the Louisiana Territory to the United States (Merriwether Lewis was also present). Secretly, however, Wilkinson was a paid agent of Spain, who communicated to Spanish officials as “Agent 13.” Writing to these officials in March 1804, he warned them of the Lewis and Clark expedition and gave his opinion that “An express ought immediately to be sent to the governor of Santa Fe … [for] a sufficient body of chasseurs to intercept Captain Lewis and his party, who are on the Missouri River, and force them to retire or take them prisoners.” Wilkinson was, however, also plotting with Jefferson’s ex-Vice President Aaron Burr to raise a filibustering expedition that would shear off parts of the states of Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina, and join them with the Louisiana Territory in a new country independent of Spain or the United States. Wilkinson found out that the plot was near to being discovered and covered his tracks, partly by pointing the finger at his erstwhile co-conspirator, as the chief witness for the prosecution against Burr during his 1807 treason trial. Almost incredibly, Jefferson did not suspect Wilkinson of double-dealing and, instead, he had appointed him in March 1805 as the new governor of the Upper Louisiana Territory. It was Wilkinson who dispatched his young friend Zebulon Pike on his expeditions, which fact has suggested to historians that Wilkinson was using the Pike expedition—and indirectly the Lewis and Clark expedition—as means to explore the territory as reconnaissance forces for his own and other conspirators’ attempts to take it over, and perhaps partly as a deliberate provocation to draw the United States and Spain into overt hostilities. After the successful return of the Lewis and Clark expedition, Jefferson in 1807 replaced Wilkinson as governor with Merriwether Lewis. On his way back to Washington to consult with various government officials in 1809, Lewis was either murdered or committed suicide (historians still disagree about this). Wilkinson was court-martialed for some of his various commercial intrigues in 1811, but was not found guilty. His role as a paid agent of Spain was not discovered until three decades after his death in 1825. He died in Mexico City and was buried there.

Review of the Library of Congress' online exhibition of Rivers, Edens, Empires: Lewis and Clark and the Revealing of America. Review of the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities (University of Nebraska-Lincoln) online exhibition of Envisaging the West: Thomas Jefferson and the Roots of Lewis and Clark. Historian Leah Glaser analyzes Jefferson's confidential letter to Congress in which he asked for funds for the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Warren L. Cook, The Flood Tide of Empire: Spain and the Pacific Northwest, 1543-1819. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973. Abraham Phineas Nasatir, ed. Before Lewis and Clark: documents illustrating the history of the Missouri, 1785-1804. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002. W. Eugene Hollon, “Zebulon Montgomery Pike and the Wilkinson-Burr Conspiracy,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 91.5 (Dec. 3, 1947): 447-456. Temple Bodley, introduction to Reprints of [William] Littell’s Political Transactions in and concerning Kentucky, and Letter of George Nicholas to His Friend in Virginia, also General Wilkinson’s Memorial. Louisville: J. P. Morton, 1926, cxxxvii-cxxix.

In the early 1800s, Thomas Jefferson owned the largest personal book collection in the U.S. After the Capitol and Congressional Library burned during the War of 1812, Jefferson allowed Congress to purchase his collection, which totaled more than 5,000 works and became the core of the Library of Congress's current collection. This website provides basic information on, and several images of, 41 of these books. They are divided by themes designated by Jefferson: "Memory," "Reason," and "Imagination," corresponding roughly to history, philosophy, and fine arts. In addition, visitors can explore lengthy selections from three of these works through the "Interactives" section: Mercy Otis Warren's History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution, Niccolo Machiavelli's The Prince, and The Builder's Dictionary, an 18th-century handbook on building design and construction. This section features a powerful zoom function, allowing visitors to view the original text in detail, as well as a transcription function. Useful for those interested in political and intellectual culture in the early republic, as well as the history of the book.

Historian Leah Glaser analyzes a letter to the U.S. Congress from Thomas Jefferson requesting funding for the Lewis and Clark expedition. In this letter, Jefferson explains his rationale and his vision for the future of the country. Glaser models several historical thinking skills, including:

This is called "Jefferson's Confidential Letter to Congress," and it certainly is more than it seems. It's often put with the collection of the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery materials. And essentially it's the letter where he asks for money from Congress, for getting money for the Corps of Discovery. And he asked for $2,500, but it's not till the very end. And what's interesting about it and the reason I like it and I teach with it, is because it's clearly not about the money. He's trying to tell Congress a much bigger story, and you really get a large idea in this one little letter of his whole theory of where the country should go and expansion and his philosophy of expansion and Indian policy and where Congress fits into it.

At the beginning you get no indication that he's going to be asking for money and what it's for or anything like that. But I think the most important phrase here is that he ends with "the public good" because that's going to be a theme throughout the letter.

Then he says, "The Indian tribes residing within the limits of the United States have, for a considerable time, been growing more and more uneasy at the constant diminution of the territory they occupy, although affected by their own voluntary sales, and the policy has long been gaining strength with them of refusing absolutely all further sale on any conditions, insomuch at this time, it hazards their friendship and excites dangerous jealousies in their minds to make any overture for the purchase of the smallest portions of their land. Very few tribes only are not yet obstinately in these dispositions."

So basically he's saying that, you know, we've been purchasing land from these Indian tribes, and all of a sudden they're not very happy about it anymore and they won't do it anymore, so we're going to have to figure something else out.

"First, to encourage them to abandon hunting, to apply to the raising stock, to agriculture and domestic manufacture, and thereby prove to themselves that less land and labor will maintain them in this, better than in their former mode of living. The extensive forests necessary in the hunting life will then become useless, and they will see advantage in exchanging them for the means of improving their farms, and of increasing their domestic comforts."

This is my favorite part of this letter, because it's basically trying to ask the Indians to do what he wants everybody to do: to be yeoman farmers. And a yeoman farmer is Jefferson's dream of the agrarian nation. The self-reliant, independent farmer who lives off his own land, and the idea that everybody will have their own land and nobody, you know, will be dependent on anybody else, and we will all be equal.

And basically he's saying we need to convince the Indians of this, too, and once they just farm they won't need any of that hunting land, and we can then easily take it from them. It won't be this big struggle. And, so this is basically a policy of assimilation. "We need them to be like us, and then they won't need all that land anymore.'

And then secondly, "To multiply trading houses among them, and place within their reach those things which will contribute more to their domestic comfort than the possession of extensive, but uncultivated, wilds. Experience and reflection will develop to them the wisdom of exchanging what they can spare and we want, for what we can spare and they want. In leading them to agriculture, to manufactures, and to civilization, in bringing together their and our settlements, and in preparing them ultimately to participate in the benefit of our governments, I trust and believe we are acting in their greatest good."

So again, we make them like our stuff, we trade stuff with them. They become sort of part of our economic system, and they become more like us, and we won't have necessarily all this conflict.

And then finally gets to that last paragraph. "While the extension of the public commerce among the Indian tribes may deprive of that source of profit such of our citizens as are engaged in it, it might be worthy the attention of Congress, in their care of individual as well as in the general interest, to the point in another direction, the enterprise of these citizens as profitably for themselves and more usefully for the public."

This again he's talking about that greater good. Yeah, there's people making money, individuals making money, but this is the bigger picture.

"It is, however, understood, that the country on that river is inhabited by numerous tribes, who furnish great supplies of furs and peltry to the trade of another nation, carried on in a high latitude through an infinite number of portages and lakes, shut up by ice through a long season. The commerce on that line could bear no competition with that of the Missouri, traversing a moderate climate, offering no competition to the best accounts, a continued navigation from its source, and possibly, with a single portage from the Western Ocean, and finding to the Atlantic a choice of channels through the Illinois or Wabash, the lakes of the Hudson, through the Ohio, the Susquehanna, or the Potomac or James rivers, and through the Tennessee and Savannah rivers."

That one line is a little sneak in here of a very important concept, which people argue was the principal reason for the Lewis and Clark expedition, and that was the Northwest Passage, all those rivers he's talking about. This theory that he has, sitting in Virginia, that there's an all-water route from the Atlantic to the Pacific. And so while we're doing this stuff with the trading houses, you know, we might just be able to find this all-water route to the Pacific.

I guess you tend to hear about the Louisiana Purchase. He's surprised, and just happens, "Oh, I wasn't thinking that at all." But you see with the date of this letter in January of 1803, that he was thinking about this area a lot before the opportunity presented itself and might have already heard rumors that France wanted to dump this land. Spain had been caring for it for a while. France was now not able to deal with all that territory. And certainly, he was not perhaps anticipating the whole block of it, but he certainly had his eye on it.

Well, we talk a lot about Jefferson's theory of the agrarian nation beforehand. I talk a lot about the yeoman farmer and the values of property and the whole—John Locke's vision of life, liberty, and property, not the pursuit of happiness, but that idea of property, even though it's dropped from the Declaration of Independence, still maintains, you know, great power and investment in his mind.

And so we talk a lot, especially when we talk about the West, of that idea of the agrarian nation. This vision that this is America's garden, and it's going—this is how we're going to be different from Europe. This is how we're going to get away from the original sin of slavery. We're not going to depend on anybody.

I give a little background about Washington's civilization program and the role that Indians play in the Constitution, then I sort of give them this and it pulls it all together a little bit, Jefferson ties it all together. And then the next day we talk about Lewis and Clark, basically, and they read his instructions. We don't pick apart every sentence necessarily, but I sort of just ask them to get into groups and outline the argument. Outline how he gets from the beginning to asking for money. What is his argument and what is he asking them to do? Why is he putting this in terms of commerce, and what does that have to do with Indians? Where do Lewis and Clark, you know, come in in all of this? How does he convince Congress that it's in their interest to fund this expedition?

Sometimes I have them read the original and sometimes I give them both, because if they really try—Jefferson has pretty good handwriting, and so they can get most of it. You know, the limitations are it's a little wordy in areas. And it is a complex argument, but that's kind of the point of the document. That's why I like it, because he makes a very simple request very complicated.

I think there's a lot of different documents as I said that would be a lot simpler, like the list given to the Indians. But, that gets specifically to the Lewis and Clark expedition. And what I think is a bonus about this is it's the precursor to the Lewis and Clark expedition, and it gives the plan in the beginning, that it wasn't all just haphazard, and that even though plans didn't always go well, over and over, the United States really did stick to Jefferson's vision as best it could. Just kept insisting the West was this place for an agrarian nation, and we're going to make it so, until [our nature] comes back and says, "No, that's not—this is not like the East. This is a different place." Even great men like Jefferson perhaps misunderstood it, but this misunderstanding is important to understand, because it had ramifications.

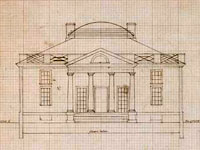

This focused site presents page images and some transcriptions of Jefferson's catalogs of books (1783 and 1789), farm book, garden book, draft of the Declaration of Independence, and some architectural documents. Visitors can browse the page images and search (where transcriptions are available) all the works. Summary descriptions are also available for each document or document type. The catalogs are Jefferson's working lists of books in his personal library. The manuscript copy of Jefferson's draft of the Declaration of Independence is not complete. The Farm Book contains Jefferson's records about his farm holdings and activities on his farms, spanning from 1774 to 1824. The Garden Book contains Jefferson's records about his gardens at Monticello and Shadwell spanning from 1766 to 1824. The architectural documents section offers more than 600 architectural drawings, sketches, and notes relating to buildings designed by Jefferson, such as Monticello and the Virginia Capitol, organized into 26 subjects.

Visitors can choose to view documents in the primary window as transcriptions (if available), as a large image, or as a small image. The search feature allows keyword search of available transcriptions. Though limited in scope, this site is useful for those interested in specific Jefferson documents.