Picturing John James Audubon

No details available.

No details available.

This 1833 caricature of Andrew Jackson lampoons the seventh president as a despotic monarch. Professor Matthew Warshauer explains some of the details.

This feature is no longer available.

This iCue Mini-Documentary uses two contemporary cartoons of the 1850s to illustrate the way in which many Southerners rationalized the institution of slavery as somehow being positive for blacks.

This feature is no longer available.

In this Face-to-face Talk, Ann Shumard of the National Portrait Gallery details the life of Samuel Morse (17911872), including his early interest in portraiture and art, his career as an inventor and his work on the telegraph, and his support of Louis Daguerre's daguerreotype.

This lecture is a repeat of node identification number 21992.

This institute explores the primary pictorial forms in American art from the British colonial settlement to the aftermath of the Civil War. The three units—portraiture, history painting, and landscape—will include a particular focus on works drawn from the National Endowment for the Humanities' new initiative "Picturing America." This NEH poster series, which has already been distributed to thousands of schools, captures 40 canonical works of American art that reflect the artistic and cultural history of the United States. Through the institute, participants will come to a deeper understanding of these works in their historical contexts and explore different methods of visual analysis. They will develop strategies and tools to use the "Picturing America" series in their classrooms.

Crop It is a four-step hands-on learning routine where teachers pose questions and students use paper cropping tools to deeply explore a visual primary source.

In our fast-paced daily activities we make sense of thousands of images in just a short glance. Crop It slows the sense-making process down to provide time for students to think. It gives them a way to seek evidence, multiple viewpoints, and a deeper, more detailed, understanding before determining the meaning of a primary source.

This routine helps young students look carefully at a primary source to focus on details and visual information and use these to generate and support ideas. Students use evidence from their “crops” to build an interpretation or make a claim. Crop It can be completed as part of a lesson, and can be used with different kinds of visual sources (for example cropping a work of art, a poem, or a page from a textbook).

Ask students to choose a source from the collection that either:

*Note: other criteria may be substituted such as choose an image that relates to a question you have about the unit, relates to your favorite part of this unit, or that represents the most important topic or idea of this unit.

Crop the image to the part that first caught your eye. Think: Why did you notice this part? Crop to show who or what this image is about. Think: Why is this person or thing important? Crop to a clue that shows where this takes place. Think: What has happened at this place?

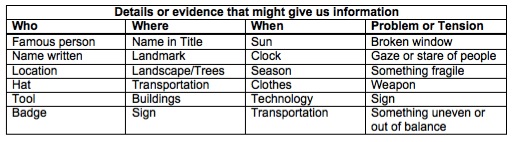

Collect the types of evidence students cropped on large chart paper by asking them to recall the different types of details that they cropped. These charts encourage students to notice details and can be used later, when adding descriptions to writing or as supports for answers during class discussions. The charts might look like the example below and will constantly grow as students discover how details help them build meaning.

Conclude the lesson by asking students what they learned about the topic related to the collection. Ask them to reflect on what they learned about looking at sources, and when in their life they might use the Crop It routine to understand something.

Avoid asking too many questions during Step Two: Explore. Keep the questions and the cropping moving fairly quickly so students stay engaged and focused on their primary source. To increase the amount of thinking for everyone, don’t allow students to share their own crops with a partner or the class right away. Ask students to revise their own crop by trying different ideas before sharing.

See Image Set Handout for samples that you might use with this strategy. These images represent some events key to understanding the Great Depression of the 1930s (e.g., FDR’s inauguration and the Bonus Army’s march on Washington) and could be used to review or preview a unit of study.

Finding Collections of Primary Sources to Crop

Find Primary Source Sets at the Library of Congress.

See this entry on finding primary sources or search Website Reviews to find useful sources.

Other Resources

Visible Thinking, Project Zero, Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Artful Thinking, Project Zero, Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Richhart, R., Palmer, P., Church, M., & S. Tishman. (April 2006). Thinking Routines: Establishing Patterns in the Thinking Classroom. Paper prepared for the American Educational Research Association.

Crop It was developed by Rhonda Bondie through the Library of Congress Teaching with Primary Sources Northern Virginia.

Video 1:

Video 2:

What arguments did women in the suffrage movement make to anti-suffrage women? TJ Boisseau suggests analyzing reformer Jane Addams's short essay "Why Women Should Vote," published in 1910. What nuances does Addams put in her arguments? How does what she says differ from other contemporary arguments for suffrage, and how is it the same? Are echoes of anything she writes about still debated today? What complications make the suffrage movement, as represented by this essay, less clear-cut than textbooks may paint it as?

A very famous essay by Jane Addams, "Why Women Should Vote," and it's recreated in many places. Jane Addams—you would probably want to introduce Jane Addams to the students first. She's a key progressive reformer and a key voice of women at the moment. She's probably the most well recognized and generally admired woman of her time. She writes an article where she says not only why should women get the vote—why women should have the vote—but she talks about why women should vote, why it is the responsibility of women to vote. She's in large part talking to a readership that is anti-suffrage and is female. So what she is trying to do is to appeal to women who are anti-suffrage. Men who were anti-suffrage were powerful voices, but when women seemed ununited on this issue it made it harder to make the claim that women should have the vote. In fact, a lot of public discussion after about 1905 was based on polls whether women wanted the vote, and if you could show that most women either didn't consider it relevant to them or felt uncomfortable with it or openly opposed it the idea was why should suffrage be granted, women don't even want it for themselves.

So she's speaking directly to women; she's trying to organize women and change women's minds, not just men's minds. I think that's probably something that the students might be surprised about as well. So when she says "Why Women Should Vote," she uses all of the social housekeeping or maternalist kinds of arguments we've talked about and we've seen in the visuals. It's three or four pages long, students can take it home, they can read it for themselves, and they can pull out, I think, easily recognized moments in the essay where she relies on those particular kinds of arguments.

One of the things I would do with that piece, which Victoria B. Brown, another historian, does so well herself, is to recognize that there is a subtle difference in Jane Addams's argument between saying that women are naturally and essentially and biologically more moral or more pure or more concerned about the health of others or more civic minded. She kind of avoids saying whether she thinks that or not, and talks about women's experiences that build those skills and build those characteristics. That's a subtlety that would be interesting to talk to students about, because a lot of students even in 2010 and beyond, I'm sure, struggle with how much they think women's nature or stereotypes about women or any other group are natural and are rooted in biology, and it is something that feminist historians have long addressed.

So Jane Addams's essay allows you to do a lot of good work around not only the particular issue of suffrage, but also the underlying ideological issues about gender that should be raised when we talk about suffrage. Because it's not just there was a movement and here's what happened, but what are the issues at that time that continue to raise themselves in our own time?

And they are reinforcing some conventional ideas that feminist historians since the 1970s have not always felt comfortable with: wanting them to have been more radical, or wanting them to have been less compromised by race or class issues. But as historians what we are really interested in is the complexity, is the messiness of it. I think bringing students to an appreciation of that is not only important, but it's what makes it interesting for them, too. I find students think one of two things—history is so easy, it's not worth studying, it's not hard like math; or history is boring because it's a chronicle of events. And I'm also bored by a chronicle of events. So, allowing them to see that there's an analytical set of issues that have to be explored triggers their curiosity and allows them to really stretch intellectually.

So I think that it's important even at a young age to bring that complexity in; otherwise we are going to bore them and not convey why this is so important. And I have taught high school myself, and I taught it at a very high level and found that students were more interested than they were when I tried to keep it at a low level in order to make sure I wasn't moving too fast or using too many big words.

Video 1:

Video 2:

In the struggle for women's suffrage, how did African American women represent themselves? What goals did they have and how did they work to reach those goals? Reading an article published in the August 1915 issue of the NAACP newsletter The Crisis, TJ Boisseau finds that activist Nannie Helen Burroughs used several arguments in favor of suffrage for African American women. Burroughs emphasized women's roles as social "housekeepers" and their differences from African American men.

I have an interesting document, actually, about why black women need the vote. Black women are also using a kind of argument from expediency after 1900. By "expediency" I mean pragmatism, practical reasons. They’re not only arguing from justice—that this is what is right—although they retain that as well.

And I think that Nannie H. Burroughs's article, that is short and something that students could easily read, makes a profound point. Nannie Burroughs, whose mother was an emancipated slave, was one of the founders of the Women's Convention of the National Baptist Convention, which is a very important locale for the Southern black women's movement. She was a black women's club leader.

The clubs that women organized at the turn of the century are more than recreational and more than philanthropic even; and certainly for black women even when they're philanthropic, it's about uplifting the race. The National Association of Colored Women's motto becomes by the 1920s "Lifting as we Climb." And so there's an idea that anyone who achieves a certain level of middle-class respectability or economic stability in the black community has a responsibility to the entire black community. Women really took that message to heart and really saw their role change by 1900.

I would read this just to make sure that students take note of the particularities here. So this isn't a visual source, but it is a powerful textual source. It reads,

"When the ballot is put into the hands of the American woman the world is going to get a correct estimate of the Negro woman. It will find her a tower of strength of which poets have never sung, orators have never spoken, and scholars have never written. Because the black man does not know the value of the ballot, and has bartered and sold his most valuable possession, it is no evidence that the Negro woman will do the same."

And here what she's referring to is the common practice—or at least not uncommon practice—of black men who otherwise would have been beaten and possibly killed for voting, pragmatically taking money in order to vote for the Democratic party, the party of the South, the party of the Confederacy for a long time. She's critical of black men for that. I think as historians and as contemporary people we need to put that in some context, she's using this as a point of contention in order to draw a very different picture for black women. But I wouldn't want students to take away her criticism of black men, without understanding the context for it.

She goes on to say, "The Negro woman, therefore, needs the ballot to get back, by the wise use of it, what the Negro man has lost by the misuse of it. She needs to ransom her race. She carries the burdens of the Church, and of the school and bears a great deal more than her economic share in the home."

In a very short space of time she has identified key tensions between black men and black women and between blacks and whites. One is that black men are not allowed to have the kinds of industrial jobs that would provide a wage that can support a family. Black women, therefore, typically need to work outside the home for a wage. Which is something that is inimical, is opposite to the idea of the middle-class woman who does not engage in wage earning, or really deals with money in any way.

So she makes that point, but she also says that the black woman carries the burden of the church and the school. So at the same time she talks about black women have sort of double duties that are unique to black women but common to women in general, which is serving the church, serving the community, making sure that schooling and other services for children are there.

What she is doing is similar to white suffragists, is taking a popular convention of the moment and twisting it to serve her purposes. To say that regardless of what you feel about putting the vote in the hands of black people, here's how it will serve your interests. She's speaking a racist language. She concludes by saying, "The ballot, wisely used, will bring to her," the Negro woman, "the respect and protection that she needs. It is her weapon of moral defense." She has made her point loud and clear and gotten the attention of both white and black readers who then might debate, at least, the argument that she has brought to the fore. And, thereby, she has accomplished her aim—by putting suffrage smack in the middle of race relations and not just gender relations.

Video 1:

Video 2:

Video 3:

How does a cartoon (c. 1910) supporting suffrage portray women? TJ Boisseau breaks down the popular views of women's roles and abilities that this cartoon uses to convince viewers to support women's right to vote. How does the cartoon make women's perceived talents as housekeepers and guardians of the private, domestic sphere important in the public world of politics?

One of the things that I would emphasize with students are the abundance of political cartoons that are produced in the first two decades of the 20th century. Mainly because this is a moment when the mass circulation of daily newspapers has reached its full potential and is reaching hundreds of thousands of customers in each city locale and also across cities.

This cartoon, which is called "The Dirty Pool of Politics," and what it shows is a fashionably dressed woman with an elaborate hat and very up-to-date and trendy clothes with a shovel, and she's shoveling dirt in front of her as she goes and the dirt is characterized as "White Slavery," Graft, Food Adulteration—and these are problems of the city, of the moment. And the point of the cartoon—which says, "Can we clean it? Give us a chance"—is to talk about how women are imagined as having a greater instinct for cleaning, a greater commitment to it, and investment of it, a set of skills and experiences that allows them to be, not only the cleaners of their own homes, but municipal housecleaners. This is a very prominent theme by the 1890s and by 1900, when suffrage becomes once again on the public consciousness and you see the merging of the two kind of rival suffrage associations—the NWSA [National Woman Suffrage Association] and the American Women's Suffrage Association—the national and the American. This is what they're going to, in a large part, base their rationale on.

So instead of what we had seen for most of the second half of the 19th century, which was an emphasis on the human right to political participation that should be shared equally by men and women, so a principle, you see a change in tactics. Not that many of the suffragists actually gave up thinking along those lines, but they certainly switched rhetoric to something they felt would be more practical, more pragmatic, and some historians have used the term expedient. The one closest to hand was the idea that women are responsible for the home and in an industrialized context the home is no longer a private domicile that a woman has control over the quality of. So if you want to be able to clean up your home, if you want—one of the things in this cartoon was food adulteration, you want to make sure that the meat that your serving your children is healthy and not rotten, that the fruit is clean and hasn't been soiled by being sitting out in an open market, if you want to make sure that the water coming into the home does not have disease in it, does not have airborne or waterborne diseases. All of those things [are] going to require the woman to actually step out of the private sphere and into the public sphere and have some political participation and some influence and control.

So this cartoon shows you right at the beginning of that movement the opportunity that women are seizing upon. To say we require the vote in order to be the traditional mothers and homemakers that we agree we primarily are. It's a very powerful and very effective and strategic argument and a cartoon like this says it in a very short punchy way.

One of the things I might demonstrate for students is to how to read the document visually. So not only how to look at the caption and think about the context and talk about the politics of the moment, but also to really look at the visual. And I emphasized at the beginning of my description that this woman is very fashionably dressed. And what that should raise for students are questions of class and also questions of how women needed to portray themselves in public in order not to violate not only the traditional idea that they are the domestic managers, but also that they need to look attractive.

So one of the other things that suffragists by the early 20th century figure out and manage to get a hold on to is that they're going to be much more publicly effective if they come across as appealing, attractive, fashionable, rather than militant in a specific way, meaning hostile to the role that women play as ornament. So you see the combining of these two things—that you can be a political person who seems to be stepping out of her sphere and not unattractive to men, and not uncaring about one's appearance. And also that this is an issue that upper-class women can grasp hold of and find an investment in, in addition to their philanthropy, in addition to their charity work, they can see political participation as something that aids them in that. Because it's not—it is their home that is at issue, but it's also poor women, immigrant women, women who have recently migrated to cities who live in tenement slums whose water is choleric, whose garbage is right outside their door—homes where they don't have any control over the quality. So, I think that cartoon says a lot and you can talk to the students for a long time about all the different aspects of this.

One of the things I would also point out and that the students are usually struck by are the demon-like figures of Food Adulteration, Graft, White Slavery, Bribery—that these are the evils that plague our society at the moment. These are the things that threaten the nation, they threaten industrial production, that these are key important issues. But if you look closely at what they are, they're also a lot about two things. Political corruption, so the idea also is that women might be more moral because they come from a sphere that is imagined as uncompromised by capitalism. So they can come in with not only fresh eyes and a fresh perspective, but they are also treading on a kind of conventional idea that has grown in the minds of many for the past century that women bring a moral sensibility. So they wouldn't stand for corruption and bribery.

White Slavery is kind of thrown in there, and that might be something that you might also talk to students about—it might take you a little bit off topic, but this is how I would keep it on topic. White slavery is the notion that women—white women—rather than black people, the whiteness there is very key, are being taken across state lines, are being forced into prostitution, being forced into sex slavery. And again this is imagined as a woman's issue, because women are thought to care about the lives of other women and about the moral turpitude or the moral character in general of society at large. So there's a lot you can do with a very concise image if you really take a look at it and mine it for all the different dimensions that it presents.

One of the reasons that I think that this is a key issue is that of course there's also an anti-suffrage movement. And it's not made up only of men who can't see past the idea that women will be their helpmates and be there for them when they get home from work—it's also made up of a good number of women—a significant portion, especially of upper-class women, who feel—who agree that women might have to step out of the private sphere into the public sphere but they want to do so much more carefully. They're much more circumspect about official roles in the public sphere, particularly the vote. And here's the logic to that—and there is a logic to that, it's not simply a misogynist or diluted or consciousness problem, it’s a logic of the argument of being a social housekeeper and the moral force in society. If your moral character comes from being protected from the public sphere, it comes from being solely responsible for the care of children and loved ones in the family unit, then the fear is that if you step too far outside of that, you yourself will lose those qualities. So what anti-suffrage women argued is that women should take responsibility for households other than their own, for the community and maybe the city at large and that there were roles for them to do so. There were professional occupations such as social worker, there were reasons to do that, but that the ballot went too far. The ballot put them in the same position as men and might actually erode the special qualities that they brought to the question of something like public health. So the public health campaign is central to the Progressive era, it becomes central to the tug of war between women over whether or not to support suffrage or not.