Richard Schumann on Patrick Henry and Independence

Richard Schumann, who interprets Patrick Henry at Colonial Williamsburg, discusses Henry's role in and leading up to the American Revolution.

Richard Schumann, who interprets Patrick Henry at Colonial Williamsburg, discusses Henry's role in and leading up to the American Revolution.

Carolyn Wilson, who interprets the historical figure Betty Randolph at Colonial Williamsburg, talks about the Randolph family, one of the first families of Virginia, focusing particularly on John and Peyton Randolph and the American Revolution.

Tom Hay, supervisor of the Courthouse at Colonial Williamsburg, looks at public protest and victimization of Loyalists in the period leading up to the American Revolution, including tarring and feathering, burning in effigy, and other public humiliations.

Jack Flintom, an interpreter at Colonial Williamsburg speaks as John Randolph, a loyalist in Virginia's climate of revolution.

Video background from The Library of Congress Webcasts site:

"On Nov. 25, 1783, the last British troops pulled out of New York City, bringing the American Revolution to an end. Patriots celebrated their departure and the confirmation of U.S. independence. But for tens of thousands of American loyalists, the British evacuation spelled worry, not jubilation. Maya Jasanoff discusses the plight of these exiles in place in her new book."

Barbara Clark Smith asks five questions of a 1775 newspaper article published by a Patriot press in Providence, RI:

This is an article that was in the newspapers, the Patriot press in the 18th century. I tend to find these normally by looking through newspapers, which are generally on microfilm or in special collections. This one, however, I found in a specific collection, which is called the American Archives, edited by Peter Force. And what Peter Force did, in the early 19th century, was go and collect records from newspapers, from state papers, committee papers, and gather them together in several volumes and publish them as part of forming a documentary history of the American Revolution. So, this is a report that appeared in the colonial press. I'm not sure exactly where, but my guess is Boston or Hartford. Possibly more than one press because they tended to copy reports from each other. That's how they got their news, from other newspapers. And it's a report from Providence, RI.

The reason I'm interested in this sort of document is that I'm trying to get a kind of "close to the ground" look at the American Revolution. I want to know what the Patriot movement was like. The movement from, say, 1765 through the Revolution of people protesting parliamentary taxation and legislation. And I want to know less about the leading men who met in conventions and congresses, and who petitioned the King. I know a fair amount about them. I want to know about people on the local ground, ordinary people, women as well as men, and I want to know what was it like for them to become Patriots. And the questions I would bring to looking at these reports and newspapers would include: What is this telling me about ordinary people's participation? Not just what ideas might they bring to joining the Revolution, or becoming a Patriot. But also what practices, what things did they have to do to be a Patriot? How do you practice being a Patriot? What does it really mean to join this movement? And what's it like, again, not in the official bodies that we think of as Patriot leaders, but kind of on the local ground, in this case in Providence, RI.

The first thing I was struck by was actually the last sentence, this image of this "Son of Liberty" going around the shops with his lampblack, which is the soot from oil lamps, a kind of black carbon soot. And unpainting the word tea. It certainly makes me think of more famous events, like the Boston Tea Party. Although that's a real destruction of other people's property, they throw tea that doesn't belong to them into the harbor in Boston. But this seems sort of a smaller offering of one's own tea. But nonetheless, something of a gathering, a really dramatic gathering, where Patriots are expressing their political views.

Elsewhere in the second paragraph it says a great number of inhabitants—you'd really like to know, how many, how many that is compared to all of the inhabitants of Providence. They mention specifically some worthy women. So we know in this case the word inhabitants includes women, which sometimes it might or sometimes it doesn't. It doesn't specifically mention anyone else. We get the impression though that this is not limited to people who were qualified to vote. Certainly if women are there, it's not limited to qualified town voters. And possibly therefore there were men and boys present—apprentices, servants, slaves, sailors, any number of people who would normally not be voting and acting politically in that way, even in a town meeting. But who could attend a marketplace to purchase things, or in this case to refuse to purchase or to give up things or to observe. So it's an interesting characterization.

One thing that I think is intriguing too is there's an argument about tea in this. It's not just a description saying people came to burn their tea. It describes tea for you. That it's needless, we don't need it. It's been detrimental to our liberty and interest and health. And that's intriguing because you can see the logic by which it's detrimental to Patriots' liberty and interest. They don't want to pay taxes on it. They don't think Parliament should be taxing this. Health is another question, and it's interesting that the Patriots raised this issue of how its supposed to be unhealthy just when Britain puts a tax on it, that's not really a common thought in the 18th century—that tea is unhealthy. In fact, people take it in part for medicinal purposes. But here it's really argued for the reader that it's needless, you simply don't need to have it.

There's other information here that you can begin to pick up. That in addition to throwing the tea in the fire, they throw in some newspapers and a printed copy of a speech by Lord North that they disapprove of. And you can go and track down what was Lord North probably speaking about. Rivington's paper, a New York paper, Rivington's a loyalist, and he's arguing on behalf of parliamentary power. Mills and Hicks. So it's interesting they throw those newspapers in the fire as well. So it's not merely getting rid of the tea. It's all that English stuff.

I think one thing to notice about it is this isn't the kind of newspaper report we would expect, that we would get, of this happening. Even though it's written in the third person by someone describing it as if he or she was there, very authoritative, "this happened." It offers opinions in places where we might expect that you'd interview someone. It doesn't interview Jane Doe and have her say, "Well, I'm really cheerful to be throwing my tea in the fire, because I don't need this noxious weed." It's the reporter telling you and the reporter using language which testifies to his—and I think we can probably use the male pronoun here—position. In reading these it's tricky. You will sometimes read pieces like this which talk about true friends of the country and lovers of freedom. And you'll discover the writer is talking about the Loyalists, the Tories, because, of course, they think too that they're the true lovers of America and freedom. So you have to sometimes read for a while to figure that out. In this case it's pretty straight forward, since they're burning Tory newspapers and throwing away tea and supporting the Sons of Liberty.

I'd really like to know more. What happened in organizing this? How did this come about? Who planned it and what was it like to attend and to observe? For example, alright, at noon you hear that you were invited to testify your good disposition to the Patriot cause by bringing your tea. Well, what does it mean if you don't feel like doing it? Does that mean if I don't bring my tea, my neighbors will, from here on out, know that I don't have a good disposition towards the Patriot cause. Does that label me a Tory who is sympathetic to Britain or to Parliamentary power?

Similarly, this point that there appeared great cheerfulness in destroying the tea. And that these worthy women made free will offerings of their stocks of the tea. Well, that's a nice description, but you do wonder about those women who maybe didn't want to burn their tea. None of that is covered. If there're women who said, "Not me, I'm keeping my tea," you don't find that out here.

And finally, I think the real clue to the question of coercion or not comes in the last sentence describing a spirited "Son of Liberty" going along the street with his brush and lampblack and unpainting the word "Tea" on the shop signs. Well, one wonders what the merchants, whose shops those were, where presumably they sold tea, thought about that. And it strikes me, that we don't have any information here, did he get permission from these merchants ahead of time? Or was this an act that put the merchants in a position where they would have to become quite unpopular with the Patriots if they decided to continue selling tea?

One of the first things I'd do is keep by me a dictionary so I could look up words, particularly a dictionary like the Oxford English Dictionary that has 18th-century meanings. Because often there's a word that will have changed in meaning. One example, they use the term, "the true interest of America." The term "interesting" which people in the 18th century would use to describe a situation, they say "that's an interesting situation." It doesn't mean, "I'm kind of interested in it intellectually," it means it involves people's economic interest, okay. They mean "interest" exactly in that sense almost all the time. And there are other examples, so one thing would be, don't be too far away from a good dictionary and preferably one that can tell you how things were used in the 18th century.

I'd certainly look for any references to people or events and make sure I knew what those were. Look in the history book, see if I could find out who's being referred to, who they assume everyone knows about. I'd go real carefully through the sentences, because 18th-century language, often the sentences are very long, with lots of different clauses which is complicated for us to understand today. And, certainly with newspapers at this time period, where they are either Patriot or Tory newspapers, I'd be looking for the point of view of the writer. In this case, the point of view is someone who's in favor the Patriots. So, that gives us the last thing which is I'd look for what isn't here. And in the case of a Patriot point of view well, we don't hear about anybody in Providence who disagreed with this. And there, we don't know if there was or was not someone. That's simply absent from this.

One is I would try to contextualize the immediate incident that's being described here, this particular event in Providence, RI. And, the way that I might do that is by looking at other events taking place in Providence, by supporting this document with other descriptions of the event. I would hope I could find in letters or diaries a description of this tea burning that took place in the marketplace. And I might particularly hope I could find a Tory, or a Loyalist point of view, somebody who was upset that this happened. And I'd go and look in diaries and letters around the time of March 2nd, and following, look for that.

The second is, after looking at that particular incident, look more broadly at other places where this took place. And it turns out if you just follow in the newspapers, and read diaries and letters from the time, tea burnings are not uncommon in 1775. A variety of them take place in New Hampshire and New Haven, certainly in the New England area, and on into the middle colonies, you can find examples of gatherings like this. So this kind of event is a second context.

The third context, I'd look at the kind of document this is, which is a report in a newspaper. And think a little bit about reading other newspapers, reading to see if this is typical or atypical. I think its reasonably typical. There are a variety of these similar reports of Patriot events in different newspapers of this time period. And to know a little something about how people are reading this. We know that newspaper subscriptions are skyrocketing at this time. And also that people are reading them in taverns. The taverns tend to subscribe. And even people who are illiterate or don't read that well, can have it read to them in taverns. So that's one of the ways this kind of document gets dispersed throughout the colonies.

And then finally I'd want to think carefully about the chronology, about the moment that this represents of March 1775. It's clearly a divisive moment and a moment when people are under some pressure, here in Providence and in other places, to take sides. To get out there and not to say, "I agree with this or that position, I agree with these rights." But vote with your feet, or in this case, vote with your tea. To show up publicly, and to denounce tea drinking and tea drinkers, and take a side and get off the fence. And that makes sense. It's March 1775, it's long after tea has been considered a terrible noxious weed that begins in the mid-1760s. It's after the Boston Tea Party, which is December of '73, so there's a precedent, these people know there's been destruction of tea, which has been very controversial. In some ways, they're maybe showing that they agree with the Tea Party. That they're having their own Tea Party, they're consuming it too, not by water but by fire. And it's after the retaliation to the Tea Party, which were the Acts to close down the port of Boston. The first Continental Congress has met and has encouraged people not to drink tea, so we know these people are supporting the Continental Congress, even though that that's never mentioned in here. And it's about let's see, a month and a little bit, before the outbreak of warfare, so its a very tense time in New England.

Yale University has made a sampling of their courses available for listeners, viewers, and readers.

As of writing, the history subsection contains six courses—two of which relate directly to U.S. history ("The American Revolution" and "The Civil War and Reconstruction Era, 1845-1877") and one which touches on relevant issues, "Epidemics and Western Society Since 1600." Each of these courses offers links to individual pages for each lecture. Lecture pages contain short text overviews of the topic at hand; a list of any reading which was required for the day; and links to lecture audio, video, and transcriptions.

Our site links you directly to the Yale's history courses. However, consider exploring other topics as well. Maybe a lecture on Roman architecture will give you background for discussing monuments in Washington, DC, or an economics course will give you a new way of thinking about the American Revolution. Interdisciplinary possibilities are endless.

Boscobel is a historic Federal neoclassical-style home, built in 1808 for States Morris Dyckman (1755-1806) and his family. The interior contains period furnishings and decorative arts, as well as an art exhibition gallery. Collection highlights include a painting by Benjamin West (1738-1820), renowned artist of historical scenes. The visitor's center presents the home's restoration. During the Revolutionary War, Dyckman was a clerk for the British Army's Quartermaster Department.

The house offers guided tours of the interior, guided tours with a tea or luncheon, educational programs in accordance with state educational standards, and picnic areas. The website offers video tours and an online collections catalog.

In 1776 56 loyalists signed the Declaration of Dependence at the Philipse Manor Hall State Historic Site.

The Manor Hall currently serves both as a local and national history museum. Highlights of the Hall include the building itself, a collection of Presidential portraits, and exhibits on local history. The website offers a brief history of the site, visitor information, and information regarding upcoming events.

I am studying the displacement of people during times of war. Were there refugees from the American Revolution? If so, who were they, why did they become refugees, and where did they go?

Contemporary Americans often picture the War for Independence as a straightforward struggle between American patriots and the British crown over the political independence of the colonies. The reality is far more complex: the colonists did not represent a homogeneous bloc, and in some senses the conflict resembled a civil war over political sovereignty in the colonies. Like all civil wars, it extracted a toll on the civilian population, many of whom who found themselves displaced and their lives disrupted by the military and political struggle being played out in North America.

Not every inhabitant of the colonies in 1776 supported the Declaration of Independence and the political break from the English crown. It is impossible to know precisely how many supporters the Patriot forces enjoyed (especially when announcing one’s allegiance was a potentially risky move), but modern historians estimate that, at most, the Patriots enjoyed a bare majority of popular support—that is, no more than half the residents of the colonies supported the cause of independence. Between one-sixth and one-fifth of the residents of the colonies remained loyal to the British crown; the remainder of the population did their best to avoid an open declaration of their sympathies, since “fence-sitting” was often the safest political and practical course.

Fully fifteen to twenty percent of the residents of the North American colonies retained their allegiance to the crown during the conflict. These loyalists presented some serious challenges to the Patriot forces mounting the War for Independence, already strained by the demands of fighting the world’s most powerful military with scarce resources and an embryonic government. Loyalists threatened to provide information or material support to British forces, and the stakes involved in the struggle—in the eyes of the Crown, after all, the Patriots advocating treason in their push for independence—led the Patriots to deal with Loyalist elements harshly at points in the struggle. Desperate to deter loyalists from overtly supporting British forces, Patriots imposed loyalty oaths on colonists suspected of British sympathies. Other Loyalists had their land confiscated; by war’s end, the hostilities had forced some 60,000 Loyalists to leave their homes in the thirteen colonies and relocate to England or to other parts of the empire.

The 1994 PBS film Mary Silliman’s War does an excellent job of demonstrating many of the tensions the War for Independence created in local communities, and the ways in which civilians caught between two warring armies attempted to continue their lives against a backdrop of conflict and civil war. The film is based on the true story of Mary Silliman, whose husband Selleck actively prosecuted Loyalists for treason as the state’s attorney for Connecticut. After winning a death sentence for two Fairfield men, their relatives kidnap Selleck and threaten to hang him if the convicted Loyalists ascend to the gallows. In charting Mary’s efforts to secure her husband’s release, the film vividly portrays the often insoluble dilemmas faced by civilians during what remained (until the 1970s) America’s longest war.

Sarah F. McMahon, "Mary Silliman's War: A Convincing Social Portrait," review of the documentary, at the website of the American Historical Association.

Images:

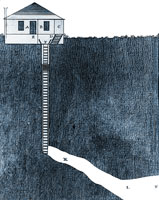

"A view of the guard-house and Simsbury-mines, now called Newgate - a prison for the confinement of loyalists in Connecticut," published in London, 1781. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

"The Procession" and "The Tory's day of Judgment," prints by Elkanah Tisdale, 1785. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.