Teaser

Help students think about where evidence for history comes from.

Description

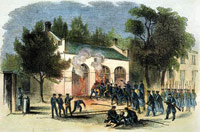

Students attempt to assign responsibility for the Boston Massacre through careful reading of primary and secondary sources and consideration of such issues as who produced the evidence, when it was produced and why was it produced.

Article Body

With iconic historical events such as the Boston Massacre it can be difficult to separate historical fact from myth. This lesson acquaints students with some of the subtleties of constructing historical accounts. It allows them to see firsthand the role of point of view, motive for writing, and historical context in doing history. The lesson opens with an anticipatory activity that helps illustrate to students how unreliable memory can be, and how accounts of the past change over time. Students then analyze a set of three different accounts of the Boston Massacre: a first-hand recollection recorded 64 years after the fact, an account written by an historian in 1877, and an engraving made by Paul Revere shortly after the event. We especially like the fact that with the first document, the teacher models the cognitive process of analyzing the source information by engaging in a “think aloud” with the document. This provides a great opportunity to uncover for students the kinds of thoughts and questions with which an historian approaches an historical source. The primary source reading is challenging, and students will likely require significant additional scaffolding to understand the meaning of the texts. Teachers may want to consider pre-teaching some of the difficult vocabulary, excerpting or modifying the text, or perhaps reading the text dramatically together as a whole class.

Topic

Revolutionary War; Boston Massacre

Time Estimate

1 class period

Rubric_Content_Accurate_Scholarship

Rubric_Content_Historical_Background

Yes

The image linked in the “materials” section offers valuable supplemental information for teachers. But minimal background information is provided for students.

Rubric_Content_Read_Write

Yes

Teachers will have to plan carefully to help students read the challenging texts. In addition, teachers may want to augment the writing portion of the lesson; the extension activity provides a great opportunity for this.

Rubric_Analytical_Construct_Interpretations

Yes

Teacher models a “think aloud” with the first document. Students replicate the process first in groups, and then individually.

Rubric_Analytical_Close_Reading_Sourcing

Yes

Identifying and evaluating source information is a key element of this lesson.

Rubric_Scaffolding_Appropriate

Yes

While appropriate for elementary school students, it could easily be adapted for middle school.

Rubric_Scaffolding_Supports_Historical_Thinking

No

Very limited vocabulary support is provided. Teachers will have to read aloud or otherwise provide additional scaffolding to assist students in understanding the documents.

Rubric_Structure_Assessment

Yes

The assessment activity provided is not thorough, and no criteria for evaluation are provided. However the extension activity provides a splendid opportunity for teachers to assess how well students have acquired the skills taught in the lesson, as well as an opportunity for students to see that these skills may be used in other situations and contexts.

Rubric_Structure_Realistic

Rubric_Structure_Learning_Goals