DC: Ninth Grade Standards

(Note: In 2011, DC public schools began transitioning to the Common Core State Standards.)

World History and Geography I: Middle Ages to the Age of Revolutions

-

Era IV: Middle Ages

-

9.1. Broad Concept: Students analyze the geographic, political, economic, social, and religious structures of the civilizations of Islam in the Middle Ages.

- Identify the physical location and features and the climate of the Arabian Peninsula, its relationship to surrounding bodies of land and water, and nomadic and sedentary ways of life. (G)

- Describe the expansion of Muslim rule through military conquests and treaties, emphasizing the cultural blending within Muslim civilization (Phoenician and Persian) and the spread and acceptance of Islam and the Arabic language. (P, R, M, S)

- Trace the origins of Islam and the life and teachings of the Prophet Muhammad, including Islamic teachings on its connection with Judaism and Christianity. (G, R)

- Explain the significance of the Qur’an and the Sunnah as the primary sources of Islamic beliefs, practice, and law, and their influence in Muslims’ daily life. (R, S)

- Trace the origins and impact of different sects within Islam, including the sources of disagreement between Suunis and Shi’ites. (R, P)

- Explain the intellectual exchanges among Muslim scholars of Eurasia and Africa and the contributions Muslim scholars made to later civilizations during the Islamic Golden Age in the areas of science, alchemy, geography, mathematics (algebra), philosophy, art, and literature. (I)

- Describe the growth of thriving cities as centers of Islamic art and learning, such as Cordoba and Baghdad.

- Describe the establishment of trade routes among Asia, Africa, and Europe; the role of the Mongols in increasing Euro-Asian trade; the prod- ucts and inventions that traveled along these routes (e.g., spices, textiles, paper, steel, and new crops); and the role of merchants in Arab society. (G, I, E)

-

9.1. Broad Concept: Students analyze the geographic, political, economic, social, and religious structures of the civilizations of Islam in the Middle Ages.

-

9.2. Broad Concept: Students understand the major events preceding the founding of the nation and relate their significance to the development of American constitutional democracy.

- Locate and identify the physical location and major geographical features of China. (G)

- Describe the reunification of China under the Tang Dynasty and reasons for the spread of Buddhism in Tang China, Korea, and Japan. (P, R)

- Analyze the development of a Confucian-based examination system and imperial bureaucracy and its stabilizing political influence. (P, R, S)

- Describe rapid agricultural, commercial, and technological development during the Song dynasties. (G, E)

- Trace the spread of Chinese technology—such as papermaking, wood-block printing, the compass, and gunpowder—to other parts of Asia, the Islamic world, and Europe. (S, I, E)

- Describe the Mongol conquest of China. (M, P)

-

9.3. Broad Concept: Students analyze the geographic, political, religious, social, and economic structures of the civilizations of medieval Japan.

- Explain the major features of Shinto, Japan’s indigenous religion. (R)

- Explain the influence of China and the Korean peninsula upon Japan as Buddhism, Confucianism, and the Chinese writing system were adopted. (G, P, R)

- Trace the emergence of the Japanese nation during the Nara (710–794) and Heian periods (794–1180). (P)

- Describe how the Heian (contemporary Kyoto) aristocracy created enduring Japanese cultural perspectives that are epitomized in works of prose such as The Tale of Genji, one of the world’s first novels. (S, I)

- Describe the Kamakura and Ashikaga Shogunates, the rise of warrior governments, and Japanese political disunity. (P)

-

9.4. Broad Concept: Students analyze the geographic, political, religious, social, and economic structures of the sub-Saharan civilizations of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai of West Africa in the Middle Ages.

- Locate and identify the site of these civilizations, the importance of the Niger River, and the relationship between vegetation zones of forest, savannah, and desert to the trade in gold, salt, food, and slaves. Illustrate the growth of the Ghana, Mali, and Songhai kingdoms/empires (e.g., trading centers such as Timbuktu and Jenne, which would later develop into important centers of culture and learning). (G, E, I)

- Describe the role of the trans-Saharan caravan trade in the changing religious and cultural characteristics of West Africa and the influence of Islamic beliefs, ethics, and law. (G, R, S)

- Trace the growth of the Arabic language in government, trade, and Islamic scholarship in West Africa. (P, S, I)

- Describe the importance of written and oral traditions in the transmission of African history and culture. (S, I)

- Trace the rise to prominence of Sundiata Keita, the legendary founder of the empire of Mali. (P)

- 6. Analyze the importance of family, labor specialization, and regional commerce in the development of states and cities in West Africa. (S, E)

- Explain the importance of Mansa Musa and his pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324. (P, R, E)

-

9.5. Broad Concept: Students analyze the geographic, political, religious, social, and economic structures of the civilizations of medieval Europe.

- Explain the geography of Europe and the Eurasian landmass, including their location, topography, waterways, vegetation, and climate, and their relationship to ways of life in medieval Europe. (G, S)

- Describe the development of feudalism and manorialism, its role in the medieval European economy, the way in which it was influenced by physical geography (the role of the manor and the growth of towns), and how feudal relationships provided the foundation of political order and private property ownership. (G, P, E)

- Demonstrate understanding of the conflict and cooperation between the Papacy and European monarchs (e.g., Charlemagne, Gregory VII, and Emperor Henry IV), the disputes over papal authority, and the Great Schism. (P, R, I)

- Explain the significance of developments in medieval English legal and constitutional practices and their importance in the rise of modern democratic thought and representative institutions (e.g., trial by jury, the common law, Magna Carta, parliament, habeas corpus, and an inde- pendent judiciary in England). (P, I)

- Describe the spread of Christianity north of the Alps and the roles played by the early church and by monasteries in its diffusion after the fall of the western half of the Roman Empire. (R)

- Describe the causes, course, and consequences of the European Crusades against Islam and their effects on the Christian, Muslim, and Jewish populations in Europe, with emphasis on the increasing contact by Europeans with cultures of the Eastern Mediterranean world. (P, R, M)

- Explain the importance of the Catholic Church as a political, intellectual, and aesthetic institution (e.g., founding of universities, political and spiritual roles of the clergy, creation of monastic and mendicant religious orders, preservation of the Latin language and religious texts, St. Thomas Aquinas’s synthesis of classical philosophy with Christian theology, and the concept of “natural law”). (P, R, I)

- Describe the economic and social effects of the spread of the bubonic plague from Central Asia to China, the Middle East, and Europe, and its impact on global population. (G, S, E)

- Explain the initial emergence of a modern economy, including the growth of banking, technological and agricultural improvements, com- merce, towns, and a merchant class. (E)

- Outline the decline of Muslim rule in the Iberian Peninsula that culminated in the Reconquista and the rise of Spanish and Portuguese kingdoms. (P, M)

-

9.6. Broad Concept: Students compare and contrast the geographic, political, religious, social, and economic structures of the Mesoamerican and Andean civilizations.

- Locate and explain the locations, landforms, and climates of Mexico, Central America, and South America and their effects on Mayan, Aztec, and Incan economies, trade, and development of urban societies. (G, E)

- Describe the highly structured social and political system of the Maya civilization, ruled by nobles and kings and consisting of many independ- ent politically sovereign states. (P)

- Explain how and where each empire arose (how the Aztec and Incan empires were eventually defeated by the Spanish in the 16th century). (P, M)

- Explain the roles of people in each society, including class structures, family life, warfare, religious beliefs and practices, and slavery. (S, R, E)

- Describe the artistic and oral traditions and architecture in the three civilizations. (S, I)

- Describe the Mesoamerican developments in astronomy and mathematics, including the calendar, and the Mesoamerican knowledge of seasonal changes to the civilizations’ agricultural systems. (I)

- Compare the development of these societies to that of other indigenous societies in North America, the Caribbean, or others in Mesoamerica or the Andes.

-

Era V: Early Modern Times to 1650

-

9.7. Broad Concept: Students describe the rise of the Ottoman Empire in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries.

- Explain the importance of Mehmed II the Conqueror and Suleiman the Magnificent. (P, M)

- Recognize the importance of the capture of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, in 1453. (P, M)

- Describe the expansion of the Ottoman Empire into North Africa, Eastern Europe, and throughout the Middle East, and describe the importance of the Battle of Lepanto in the 16th century limiting Ottoman ambitions in the Mediterranean. (G, M)

- Summarize the rise of the Safavid Empire.

- Describe Shah Abbas and how his policies of cultural blending led to the Golden Age of the Safavid Empire.

-

9.7. Broad Concept: Students describe the rise of the Ottoman Empire in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries.

-

9.8. Broad Concept: Students analyze the origins, accomplishments, and geographic diffusion of the Renaissance.

- Trace the emergence of the Renaissance, including influence from Moorish (or Muslim) scholars in Spain. (G, P, S)

- Explain the importance of Florence in the early stages of the Renaissance and the growth of independent trading cities (e.g., Venice) and their importance in the spread of Renaissance ideas. (G, S, E)

- Explain the effects of the reopening of the ancient Silk Road between Europe and China, including Marco Polo’s travels and the location of his routes. (G, E)

- Compare and contrast the similarities and differences between the Northern and Southern Renaissance. (P, I)

- Describe the way in which the revival of classical learning and the arts fostered a new interest in humanism (i.e., a balance between intellect and religious faith). (R, I)

- Describe the growth and effects of new ways of disseminating information (e.g., the ability to manufacture paper, translation of the Bible into vernacular, and printing). (I, S)

- Outline the advances made in literature, the arts, science, mathematics, cartography, engineering, and the understanding of human anatomy and astronomy (e.g., by Dante Alighieri, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, Johann Gutenberg, and William Shakespeare). (I)

-

9.9. Broad Concept: Students analyze the historical developments of the Reformation.

- Explain the institution and impact of missionaries on Christianity and the diffusion of Christianity from Europe to other parts of the world in the medieval and early modern periods. (G, R)

- Locate and identify the European regions that remained Catholic and those that became Protestant and how the division affected the distribution of religions in the New World. (G, R)

- Explain the supremacy of the Catholic Church, the growth of literacy, the spread of printed books, the explosion of knowledge and the Church’s reaction to these developments.

- List and explain the causes for the internal turmoil within and eventual weakening of the Catholic Church (e.g., tax policies, selling of indul- gences, England’s break with the Catholic Church). (P, R)

- Outline the reasons for the growing discontent with the Catholic Church, including the main ideas of Martin Luther (salvation by faith) and John Calvin (predestination) and their attempts to reconcile God’s word with Church action. (P, R)

- Explain Protestants’ new practices of church self-government and the influence of those practices on the development of democratic practices and ideas of federalism. (P, R)

- Describe the Golden Age of cooperation between Jews and Muslims in medieval Spain that promoted creativity in art, literature, and science. (S, E)

- Explain how that cooperation was terminated by the religious persecution of individuals and groups (e.g., the Spanish Inquisition and the expulsion of Jews and Muslims from Spain). (R, S)

-

9.10. Broad Concept: Students describe the rise of English Colonial Empires.

- Identify the voyages of discovery, the locations of the routes, and the influence of cartography in the development of a new European worldview. (G, I)

- Describe the goals and extent of Dutch, English, French, and Spanish settlements in the Americas. (G, P)

- Explain the development and effects of the Atlantic slave trade. (S, E)

- Describe the exchanges of plants, animals, technology, culture, ideas, and diseases among Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries and the major economic and social effects on each continent. (G, S, E)

-

9.11. Broad Concept: Students explain political and social developments in China and Japan in an era of expanding European influence.

- Describe Chinese power and technology through Zheng He’s voyages (the Ming Dynasty). (G, P)

- Explain the effects of European contacts on China and Japan. (G, P)

- Describe Japan’s unification, after years of civil war, and the establishment of centralized feudalism under the Tokugawa shoguns. (P)

- Explain the influence of a rigid class system, the Samurai elites, and Tokugawa isolationist’s policies on Japanese government and society. (P, S)

- Trace the rise of the early Ching Dynasty in China and growing European demand for Chinese goods, such as tea and silk. (P, E)

-

9.12. Broad Concept: Students summarize political and social developments on the Indian Subcontinent during the Mughal eras and the beginnings of British political dominance.

- Trace the influence of the following great Mughal rulers on the subcontinent: Babur, Akbar, and Arangzeb. (P)

- Characterize the development of the Sikh religion. (R)

- Describe the art and architecture (e.g., the Taj Mahal) during the Mughal period. (I)

- Trace the growing economic and political power of the British East India Company in key cities on the subcontinent. (P, E)

-

Era VI: The Age of Revolutions

-

9.13. Broad Concept: Students analyze the historical developments of the Scientific Revolution and its lasting effect on religious, political, and cultural institutions.

- Describe the roots of the Scientific Revolution (e.g., Greek rationalism; Jewish, Christian, and Muslim science; Renaissance humanism; new knowledge from global exploration). (R, I)

- Explain the significance of new scientific theories, the accomplishments of leading figures (e.g., Bacon, Copernicus, Descartes, Galileo, Kepler, Linnaeus, and Newton), and new inventions (e.g., the telescope, microscope, thermometer, and barometer). (I)

-

9.13. Broad Concept: Students analyze the historical developments of the Scientific Revolution and its lasting effect on religious, political, and cultural institutions.

-

9.14. Broad Concept: Students analyze political, social, and economic change as a result of the Age of Enlightenment in Europe.

- Explain how the main ideas of the Enlightenment can be traced back to such movements and epochs as the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Scientific Revolution, the Greeks, the Romans, and Christianity. (P, I)

- Describe the accomplishments of major Enlightenment thinkers (e.g., John Locke and Charles-Louis Montesquieu). (P, I)

- Explain the origins of modern capitalism; the influence of mercantilism and the cottage industry; the elements and importance of a market economy in 17th-century Europe; the changing international trading and marketing patterns, including their locations on a world map; and the influence of explorers and mapmakers. (E)

-

9.15. Broad Concept: Students compare and contrast the Glorious Revolution of England, the American Revolution, the Spanish American Wars of Independence, and the French Revolution, and their enduring effects on the political expectations for self-government and individual liberty.

- Identify and explain the major ideas of philosophers and their effects on the democratic revolutions in England, the United States, France, and Latin America (e.g., John Locke, Charles-Louis Montesquieu, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Simón Bolívar, Toussainte L’Ouverture, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison). (P, I)

- List and explain the principles of the Magna Carta, the English Bill of Rights (1689), the American Declaration of Independence (1776), the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen (1789), and the U.S. Bill of Rights (1791). (P)

- Explain the significance of the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804). (P, S, I)

- Understand the unique character of the American Revolution, its spread to other parts of the world, and its continuing significance to other nations. (P, I)

- Explain how the ideology of the French Revolution led France to evolve from constitutional monarchy to democratic despotism to the Napoleonic Empire. (P, I)

- Describe the initial uprisings against the mother country in Spanish America, describe their takeover by the largely indigenous masses, and explain the outcomes of these movements. (P, I)

- Describe how nationalism spread across Europe with Napoleon but was repressed for a generation under the Congress of Vienna and Concert of Europe until the Revolutions of 1848. (P)

- Students compare the present with the past, evaluating the consequences of past events and decisions and determining the lessons that were learned.

- Students analyze how change happens at different rates at different times, understand that some aspects can change while others remain the same, and understand that change is complicated and affects not only technology and politics but also values and beliefs.

- Students show the connections, causal and otherwise, between particular historical events and larger social, economic, and political trends and developments.

- Students recognize the complexity of historical causes and effects, including the limitations on determining cause and effect.

- Students distinguish intended from unintended consequences.

- Students interpret past events and issues within the context in which an event unfolded rather than present-day norms and values.

- Students understand the meaning, implication, and impact of historical events and recognize that events could have taken other directions.

- Students conduct cost-benefit analyses and apply basic economic indicators to analyze the aggregate economic behavior of the U.S. economy.

- Students understand the influence of physical and human geographic factors on the evolution of significant historic events and movements. They apply the geographic viewpoint to local, regional, and world policies and problems.

- Students use a variety of maps and documents to interpret human movement, including major patterns of domestic and international migration, changing environmental preferences and settlement patterns, the frictions that develop between population groups, and the diffusion of ideas, technological innovations, and goods. Identify major patterns of human migration, both in the past and present.

- Students relate current events to the physical and human characteristics of places and regions. They identify the characteristics, distribution, and complexity of Earth’s cultural mosaics.

- Students evaluate ways in which technology has expanded the capability of humans to modify the physical environment and the ability of humans to mitigate the effect of natural disasters.

- Students hypothesize about the impact of push-pull factors on human migration in selected regions and about the changes in these factors over time. Students develop maps of human migration and settlement patterns at different times in history and compare them to the present.

- Students note significant changes in the territorial sovereignty that took place in the history units being studied.

- Students study current events to explain how human actions modify the physical environment and how the physical environment affects human systems (e.g., natural disasters, climate, and resources). They explain the resulting environmental policy issues.

- Students explain how different points of view influence policies relating to the use and management of Earth’s resources.

- Students identify patterns and networks of economic interdependence in the contemporary world.

- Students distinguish valid arguments from fallacious arguments in historical interpretations (e.g., appeal to false authority, unconfirmed citations, ad hominem argument, appeal to popular opinion).

- Students identify bias and prejudice in historical interpretations.

- Students evaluate major debates among historians concerning alternative interpretations of the past, including an analysis of authors’ use of evidence and the distinctions between sound generalizations and misleading oversimplifications.

- Students construct and test hypotheses; collect, evaluate, and employ information from multiple primary and secondary sources; and apply it in oral and written presentations.

In addition to the standards for grades 9 through 12, students demonstrate the following intellectual, reasoning, reflection, and research skills.:

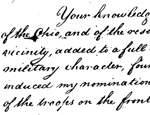

The template for the computer interactive is a real rough draft of the Declaration of Independence, complete with edits made by Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin. On the "Overview" page, students can scroll their mouse over Thomas Jefferson's original script, transforming sections from the original handwriting to student-friendly printed font with word-processor-style edits.

The template for the computer interactive is a real rough draft of the Declaration of Independence, complete with edits made by Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin. On the "Overview" page, students can scroll their mouse over Thomas Jefferson's original script, transforming sections from the original handwriting to student-friendly printed font with word-processor-style edits.