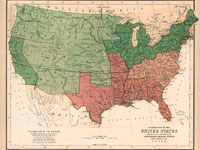

After the War of 1812, the northern, free states' members in the House of Representatives exceeded those from slave states. The slave states reckoned then that Congress could try to outlaw slavery in the South. Their representatives in the House had tried to stave off attempts by that chamber to legislate the abolition of slavery by instituting a "gag rule" which, for years, had blocked abolitionist petitions from reaching the floor of the House, but which had been rescinded in 1844. The South therefore worked out a strategy to ensure that they would not be outnumbered in the Senate. If they maintained a balance in the Senate, they figured, attempts to force the end of slavery on the southern states could be blocked.

To maintain this balance as new territories were admitted into the Union, slave states and free states were admitted, roughly speaking, in pairs: Mississippi and Indiana, Alabama and Illinois, Missouri and Maine, Arkansas and Michigan, and Florida and Iowa. In some cases, the admission of a state was slowed or sped up in order to pair it with another. This practice was the outcome of a strategy that the South considered essentially defensive. The South's primary aim in this was not so much to spread slavery as it was to protect slavery where it already existed. To do that, it had to protect its strength in the Senate, and for that to happen as northern territories were brought into the Union, the South had to find southern territories to balance them. Eventually, this even led some in the South to look for possible ways to annex Cuba and Nicaragua and bring them into the Union as slave states.

Texas and Wisconsin were considered to be a pair. Partly due to objections of northern abolitionists who feared that the admission of Texas by itself would tilt the Senate balance in favor of the South, the Lone Star State's entrance into the Union was delayed until December 29, 1845, and only happened then because of the successful Democratic campaign of 1844 that succeeded in electing James Polk to the White House on a platform that combined a call for admitting Texas into the Union with an expansionist stance on the question of setting the northern territorial claims of Oregon as far as possible. The northern vote was split in that election, between Whig candidate Henry Clay, Liberty Party candidate James Birney, and James Polk (partly because of his party's position on Oregon), giving the election to Polk.

There was a strong effort to bring Wisconsin into the Union in 1846, along with Iowa, but Wisconsin was not admitted until May 29, 1848. Did that make the Senate balanced in the South's favor between the time of the admission of Texas and the admission of Wisconsin? Not really. For one thing, the balance in fact was volatile.

For example, although Iowa had been admitted to the Union as a free state on December 28, 1846, political turmoil in its state legislature, almost evenly divided on party lines, and spiced by accusations of bribery, resulted in the state's inability at first to elect U.S. Senators to send to Congress. In addition, party politics factored into votes, with northern Democrats, for example, sometimes voting with their southern colleagues. Nevertheless, a rough parity existed in the Senate, although the South recognized it as tenuous.

South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun's speech in the Senate on February 19, 1847, described the situation in which the South perceived itself at the time:

Sir, already we are in a minority—I use the word 'we' for brevity sake—already we are in a minority in the other House, in the electoral college, and, I may say, in every department of this government, except at present, in the Senate of the United States—there, for the present, we have an equality. Of the twenty-eight States, fourteen are non-slaveholding and fourteen are slaveholding, counting Delaware, which is doubtful, as one of the non-slaveholding States. But this equality of strength exists only in the Senate. … We, Mr. President, have at present, only one position in the government, by which we may make any resistance to this aggressive policy which has been declared against the South; or any other, that the non-slaveholding States may choose to take. And this equality in this body is of the most transient character. Already, Iowa is a State; but, owing to some domestic calamity, is not yet represented in this body. When she appears here, there will be an addition of two Senators to the Representatives here, of the non-slaveholding States. Already, Wisconsin has passed the initiatory stage, and will be here at next session. This will add two more, making a clear majority of four in this body on the side of the non-slaveholding States, who will thus be enable to sway every branch of this government at their will and pleasure. But, sir, if this aggressive policy be followed—if the determination of the non-slaveholding States is to be adhered to hereafter, and we are to be entirely excluded from the territories which we already possess, or may possess—if this is to be the fixed policy of the government, I ask what will be our situation hereafter?

Calhoun was reacting here to the introduction of the "Wilmot Proviso," an attempt by northern anti-slavery congressmen to ban slavery in all territories that would enter U.S. possession in the future. Far from seeing itself at this point as capable of taking advantage of its senatorial strength, the South—as is clear from Calhoun's speech—saw itself as barely able to hold its defenses against an aggressive North intent on outlawing slavery everywhere. In his speech, Calhoun calculated that if all the territories were thenceforth brought into the Union as free states, the slave states would be outnumbered in the Senate by two to one.

The Wilmot Proviso was defeated in the Senate—that was as close as one could say that the South was able to "take advantage of" its strength there—but the battle over it served to turn opposing political forces further into sectional differences, North versus South, free state versus slave state. By doing this, it also helped to redefine the politics of the time away from party affiliation and loyalty to sectional affiliation. Both the Whigs and the Democrats underwent fragmentation and inner realignments during this period.

When California was admitted on September 9, 1850, its formal admission came only five days after the passage of the bills that formed the Compromise of 1850. As part of the Compromise, California came in as a single free state, rather than divided into two parts, one free and one slave, but Utah and New Mexico territories were organized to allow popular votes in the territories to decide later whether slavery would be permitted. In point of fact, the admission of California did not immediately change the balance of anti- vs. pro-slavery votes in the Senate because California, although a free state, sent one anti-slavery senator and one pro-slavery senator to Washington.

![[James Madison located bottom center] Painting, Close up of "Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States," 1940, Howard Chandler Christy, Wikimedia Commons Painting, Close up of "Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United St](/sites/default/files/oldimage.jpg)