Women's Suffrage: Jane Addams's Article

Video 1:

- Cover. Ladies Home Journal, January 1910.

- Addams, Jane. "Why Women Should Vote." Ladies Home Journal, January, 1910.

- Photo. "Jane Addams, head and shoulders portrait, facing left." Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction No. LC-USZ62-95722.

- Photo. "Jane Addams." c.1914. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction No. LC-USZ62-1059.

- Image. Milwaukee County League of Woman Voters. "Vote." Wisconsin Historical Society, Ephemera Collection, 1850-2000, Image ID #37894.

- Image. McLoughlin Brothers. Suffragette Paper Dolls. 1915.

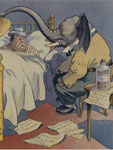

- Illustration. Keppler, Udo. "The Feminine of Jekyll and Hyde." Puck Magazine, June 4, 1913. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction No. LC-DIG-ppmsca-27952.

- Illustration. "The Audience Was Caught Off Its Feet," from "Coals of Fire." Scribner's Magazine, January 1915.

- Photo. "A Group of Suffragettes Who Were Arrested For Picketing." in "The Prison Special: Memories of a Militant." Scribner's Magazine, June 1922.

- Photo. Yellow Ribbon from 1911 Suffrage Parade. Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection.

Video 2:

- Illustration. Grant, Gordon. "Giddap!" Puck Magazine, March 14, 1914. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction No. LC-USZC2-1184.

- Poster. Grant, Gordon. "The Public Health Nurse She answers humanity's call : Your Red Cross membership makes her work possible." 1914–1918. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction No. LC-USZC4-7760.

- Cartoon. "Election Day!" Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction No. LC-USZ62-51821.

- Illustration. "Women Writers Suffrage League." International Women Suffrage Congress, 1913. New York Public Library Digital Gallery, Image ID: 1536719.

What arguments did women in the suffrage movement make to anti-suffrage women? TJ Boisseau suggests analyzing reformer Jane Addams's short essay "Why Women Should Vote," published in 1910. What nuances does Addams put in her arguments? How does what she says differ from other contemporary arguments for suffrage, and how is it the same? Are echoes of anything she writes about still debated today? What complications make the suffrage movement, as represented by this essay, less clear-cut than textbooks may paint it as?

A very famous essay by Jane Addams, "Why Women Should Vote," and it's recreated in many places. Jane Addams—you would probably want to introduce Jane Addams to the students first. She's a key progressive reformer and a key voice of women at the moment. She's probably the most well recognized and generally admired woman of her time. She writes an article where she says not only why should women get the vote—why women should have the vote—but she talks about why women should vote, why it is the responsibility of women to vote. She's in large part talking to a readership that is anti-suffrage and is female. So what she is trying to do is to appeal to women who are anti-suffrage. Men who were anti-suffrage were powerful voices, but when women seemed ununited on this issue it made it harder to make the claim that women should have the vote. In fact, a lot of public discussion after about 1905 was based on polls whether women wanted the vote, and if you could show that most women either didn't consider it relevant to them or felt uncomfortable with it or openly opposed it the idea was why should suffrage be granted, women don't even want it for themselves.

So she's speaking directly to women; she's trying to organize women and change women's minds, not just men's minds. I think that's probably something that the students might be surprised about as well. So when she says "Why Women Should Vote," she uses all of the social housekeeping or maternalist kinds of arguments we've talked about and we've seen in the visuals. It's three or four pages long, students can take it home, they can read it for themselves, and they can pull out, I think, easily recognized moments in the essay where she relies on those particular kinds of arguments.

One of the things I would do with that piece, which Victoria B. Brown, another historian, does so well herself, is to recognize that there is a subtle difference in Jane Addams's argument between saying that women are naturally and essentially and biologically more moral or more pure or more concerned about the health of others or more civic minded. She kind of avoids saying whether she thinks that or not, and talks about women's experiences that build those skills and build those characteristics. That's a subtlety that would be interesting to talk to students about, because a lot of students even in 2010 and beyond, I'm sure, struggle with how much they think women's nature or stereotypes about women or any other group are natural and are rooted in biology, and it is something that feminist historians have long addressed.

So Jane Addams's essay allows you to do a lot of good work around not only the particular issue of suffrage, but also the underlying ideological issues about gender that should be raised when we talk about suffrage. Because it's not just there was a movement and here's what happened, but what are the issues at that time that continue to raise themselves in our own time?

And they are reinforcing some conventional ideas that feminist historians since the 1970s have not always felt comfortable with: wanting them to have been more radical, or wanting them to have been less compromised by race or class issues. But as historians what we are really interested in is the complexity, is the messiness of it. I think bringing students to an appreciation of that is not only important, but it's what makes it interesting for them, too. I find students think one of two things—history is so easy, it's not worth studying, it's not hard like math; or history is boring because it's a chronicle of events. And I'm also bored by a chronicle of events. So, allowing them to see that there's an analytical set of issues that have to be explored triggers their curiosity and allows them to really stretch intellectually.

So I think that it's important even at a young age to bring that complexity in; otherwise we are going to bore them and not convey why this is so important. And I have taught high school myself, and I taught it at a very high level and found that students were more interested than they were when I tried to keep it at a low level in order to make sure I wasn't moving too fast or using too many big words.