The goals of U.S. foreign policy toward Egypt during the 1950s were to protect American and western European access to oil in the Middle East, to end British colonial rule throughout the area in line with the ideal of self-determination expressed in the Atlantic Charter, to contain the expansion of communism and particularly the influence of the Soviet Union in the region, and to support the independence of Israel without alienating the Arab states.

In all this, the U.S. State Department regarded Egypt as the natural leader among the Arab states and sought to make it an ally and to encourage pro-Western elements in Egyptian society.

The Basic U.S. Strategy

One essential problem was that the various goals of U.S. policy toward Egypt were often at odds with one another. As one example, the U.S. was sympathetic to Egypt's desire to free itself from British colonial rule--just as the U.S. had done--and emphasized its support for full Egyptian self-rule to the country's political and military leaders. But the U.S. was also allied with Britain to oppose the Soviet Union's expansion into Europe.

Almost all of Europe's oil at the time came through the Suez Canal. Britain was divesting itself of its empire, but in Egypt it had strong concerns about leaving the Suez Canal undefended. Britain's lingering military presence in the Mideast helped protect oil shipping lanes, the canal, and the oil fields from the threat posed by the Soviet Red Army. For its part, Egypt simply wanted Britain out and was disappointed when the U.S. did not always take its side.

Another example of internally conflicting goals--the U.S. supported "peoples' right to self-determination." This was, in fact, one way of framing why the U.S. opposed communism and the Soviet Union in particular: because it was totalitarian and crushed individuals' liberties. However, the U.S. had in mind a model of self-governance that assumed its own historical situation and that of other western European states who were the heirs of the Enlightenment and its ideals of individual autonomy. Other places were not necessarily burgeoning libertarian strongholds that only wanted a chance to grow to fruition as western-style capitalist democracies.

Eisenhower's Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, approached this dilemma by applying a "Marshall Plan" strategy of massive aid to places such as the Middle East, Asia, and Africa, while also implicitly dealing with the fact that in these places (unlike in the European countries with strong democratic traditions that had been devastated by World War II), the "people" were not necessarily committed to turning their countries into capitalist, pro-western democracies.

Dulles's State Department believed that countries such as Egypt, for example, would naturally undergo a two-step process. First, relatively corrupt old regimes would be cast aside (least destructively, by military coups) and the governments would then be controlled by relatively authoritarian regimes that would pull together and organize the country's various factions. Second, with development aid and the establishment of trade ties with the rest of the world, the countries would emerge (through a peaceful evolutionary process, it was hoped) as full-fledged democracies.

Even if this were a true description of the "natural" evolution of Third World countries, however, none of this could happen in isolation. Larger political forces, outside the individual countries, affected their internal politics.

For the U.S., Dulles's goal of opposing and, as he framed it, "containing" the expansion of the totalitarianism of the Soviet Union and China provided a dilemma. When colonial powers disengaged from their former colonies in the Third World, the power vacuum that resulted meant that the U.S. found itself in various places giving its support to indigenous, but authoritarian and even dictatorial, regimes. This, it was thought, would cordon off these countries' borders, as it were, against communist intrusion and provide an opportunity for the U.S. to engage there in what the State Department came to call "nation building," which generally meant the infusion of massive economic and military aid. The eventual goal was the peaceful evolution of these countries into functioning, pro-western democracies.

This was the template for U.S. policy toward Egypt in the 1950s. Unfortunately for its prospects of success, it was only partly congruent with Egypt's own perceived interests. In particular, Egypt's leaders were generally never sympathetic to communism, but they did not fear anything like a takeover by the Soviet Union. In fact, following a long established practice in Mideast diplomatic circles, they looked for ways to play off one great power against another to their advantage.

Egypt had centuries of experience in warding off the domination of great powers by playing them against one another. When the U.S. stalled in advancing Egypt's positions against Britain, Egypt sought to engage with the Soviet Union, partly because that was where it could find military and economic support and partly because it was a way to exact more concessions from the U.S. in return.

In addition, the political power that Egyptian leaders wielded, like that in other countries in the region, was weak. In a way that American diplomats did not understand, Mideast leaders had to adjust their countries' alliances constantly with one another and could not make permanent, unilateral alliances. It was an Egyptian goal to enhance its own power in the region, not as the leader of a pro-American alliance.

Initial Post-World War II Problems for the U.S. and Egypt

Beginning with President Roosevelt's meeting with King Farouk at the end of World War II, American diplomats (including Truman's Secretary of State Dean Acheson) assured Egyptian leaders that the U.S. supported the country's efforts at self-determination. The Egyptians unfailingly heard these assurances to mean that the U.S. would help them rid Egypt of Britain. Sometimes, however, U.S. diplomats used this sort of language to mean that the U.S. would protect Egypt from communist subversion, internally or externally, from the Soviet Union. This miscommunication caused confusion.

Internal Egyptian politics made Egyptian King Farouk align himself increasingly with factions that demanded an immediate abrogation of an earlier treaty that allowed Britain to continue control over the Suez Canal and that Britain pull all its troops out of Egypt. The U.S. found the King to be unsympathetic to America's reluctance to go along with the demand for Britain to abandon Egypt and the canal immediately. To the U.S., it seemed that political power in Egypt was rapidly being corrupted and that it was flowing "down the drain," out to the more radical political factions.

The U.S. State Department concluded that it would find a more sympathetic hearing from another ruler. Historians have reached different conclusions about the extent of the involvement of U.S. diplomats and CIA operatives at this juncture, but it seems fairly clear that they met with dissatisfied Egyptian military officers and at least promised them that if there was a military coup, that the U.S. would not oppose it, and that the U.S. would prevent possible British opposition to it, as long as foreign nationals and property were protected.

The coup occurred in July 1952. Two military officers, General Mohammed Naguid and Colonel Gamel Abdel Nasser, emerged as the new Egyptian leaders. The military government immediately asked for U.S. military and economic aid. A State Department official agreed, but the Secretary of State and the President balked at the deal, which caused internal political problems for the Egyptian leaders.

U.S. Efforts Intensify after Truman and Acheson Give Way to Eisenhower and Dulles

President Truman and Secretary of State Acheson were succeeded by President Eisenhower and Secretary of State Dulles in 1953. Dulles' brother Allen was made director of the CIA.

The Dulles brothers provided military advisors and equipment to the Egyptian army. Through clandestine contacts, both the State Department and the CIA gave Egyptian leaders, especially Nasser, important intelligence training and assistance in moderating potential internal political rivals and in conducting propaganda campaigns.

In 1954, Nasser edged out Naguid and ascended to sole leadership of the military government. During the tumult surrounding this, Nasser was able to disband the main faction of his opposition, the Moslem Brotherhood, after an assassination attempt during one of his speeches, in which the would-be assassin fired seven shots at him, but missed. Public sympathy for Nasser surged, allowing him to quash his opposition. Nasser's chief of security much later admitted that the CIA had given Nasser a bulletproof vest, which he was wearing during his speech, raising the issue of whether the assassination attempt was a setup, designed to benefit Nasser.

Egypt looked for military equipment and aid. During this period, both State and the CIA provided it, sometimes clandestinely, hoping for a formal military alliance with Egypt, and for Egypt to take the lead in reaching a peace settlement with Israel. Egypt, however, extracted as much military and economic assistance from the U.S. as it could, but refused a military alliance with the West. It was Nasser's intention to adopt a policy of "neutralism" between West and East (that is, between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R.) in order to maintain its own independence, and, in fact, to heighten competition between the two in the region in order to fend off domination and to gain as much aid as possible from each.

U.S. Hopes for a Mideast Pro-Western Alliance

The U.S. recognized that by the mid-1950s the U.S.S.R. had developed a Third World strategy of pouring vast amounts of money and material into countries in Asia, Africa, and the Mideast that had recently been colonies of Western countries. The Soviets hoped to counter Western influence in these countries by promoting anti-colonial sentiment and supporting socialist reform there. The strategy was quite successful, at least for a time. The result was that in much of the Third World, the Soviet Union was viewed more favorably than the United States.

The U.S. and Britain attempted to form a cordon of defensive alliances around the world in order to prevent Soviet expansion. This included NATA in Europe and SEATO in Southeast Asia. The initial plan also included a Mideast alliance to bridge the gap between the two, but when the U.S. and Britain began formalizing agreements with Turkey and Iraq (rivals of Egypt in regional influence), Nasser felt that they had discarded Egypt. Nasser's idea was to form a regional military alliance within the Arab League, with him as leader. The souring of relations between Nasser and the West resulted in a turning point in 1955 in which Nasser asked for, and received, large-scale military equipment sales from the Soviet Union, and distanced his country and himself from the United States. Indeed, he adopted socialist reforms and heavily promoted "pan-Arab nationalism," as well as "neutralism" and "noncooperation with the West."

Despite that, the U.S. continued to court Nasser with economic aid, which indeed he was happy to receive. The U.S. accepted that a "neutralist" Egypt was better than a communist one, and recognized that the Soviets, from this time, intended to block Western efforts to cordon them and, to do that, were encouraging vast sales of its military equipment all over the region, as well as supporting the idea of Arab nationalism, especially in opposition to Israel. The U.S. pressured Israel and Egypt to make concessions toward a settlement, with the intention of avoiding war and reducing Soviet influence in the region.

The U.S. Ends Its Balancing Act

When the U.S. found that Nasser and Israeli Prime Minister Ben Gurion were ultimately unable or unwilling to conclude a peace agreement, President Eisenhower and Secretary of State Dulles opted to call Nasser's bluff by countering him in several covert ways, especially in promoting relations with his regional Arab rivals in Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Libya. The U.S. calculated that Nasser, confronted by the possibility that the other Arab states were aligning with the West, would find himself in a situation that he would find unacceptable--namely, with only one powerful "friend," the Soviet Union.

In order to avoid such an outcome, the U.S. believed, Nasser would become more tractable to a peace settlement with Israel, so that he would not be left behind, relative to the other Arab states. In response, Nasser stepped up anti-American rhetoric in the region and, in return from the Soviets for help in setting up covert intelligence operations in the region designed to undermine the Arab monarchies of Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Libya, and Iraq, Nasser agreed to accept Soviet military assistance.

The denouement occurred over the plans to construct the Aswan High Dam, which the U.S. had been willing to fund, but which the Soviet Union had told Nasser that it would also be willing to do. Secretary of State Dulles, with Eisenhower's agreement, finally decided to extract the U.S. from situations in the Third World in which the countries were deliberately playing them off against the Soviet Union. In 1956, Dulles let it be known to Nasser that the U.S. would not fund the dam, believing that Nasser's only other option to finance it was to accept the Soviet Union's offer. This, Dulles believed correctly, Nasser would be highly reluctant to do. Nasser responded by opening diplomatic relations with China.

The Suez Crisis

Nasser also had another option that the U.S. did not anticipate: He suddenly took an enormously dangerous risk and nationalized the Suez Canal, anticipating that Egypt could use the canal revenues to finance the construction of the Aswan High Dam without U.S. or Soviet funding.

In response, three months later, Britain, France (the two foreign shareholders in the canal), and Israel attacked Egypt, resulting in a quick and decisive military defeat for Egypt. The Israelis occupied a large portion of the Sinai Peninsula, and the Anglo-French forces occupied Port Said and Port Fouad at the Mediterranean terminus of the Suez Canal. All of this they did without consulting the U.S.

Eisenhower and Dulles were appalled at the attack. They believed with some good evidence that it would result in a military response from the Soviet Union, risking a much larger war, and, in any event, would throw the weight of public opinion throughout the Arab Middle East entirely against the West and into the Soviet camp. The U.S., therefore, strongly and publicly opposed the invasion and worked in the U.N., especially with Canada, to pass a cease-fire resolution and a call for the withdrawal of military forces.

In addition, the U.S. pressured Britain by threatening to sell the British bonds it held, which would have forced a devaluation of the British currency and threatened Britain's ability to import food and oil. The British relented, a cease-fire was called, and the occupying forces were evacuated.

In the Suez Crisis, the Third World in general and the Arab states in particular saw the U.S. as having acted as its friend. Despite Egypt's military loss, Nasser remained in power with the Suez Canal under Egypt's control, and the British, French, and Israelis evacuated the region they had invaded.

The Eisenhower Doctrine

For the next few years, U.S. policy toward Egypt was guided by what became known as the "Eisenhower Doctrine," a declaration that the U.S. was prepared to offer assistance to any Middle Eastern country (if it asked for assistance) in order to oppose the military threat of "any nation controlled by international communism." In reality, the doctrine was fairly impractical for a number of reasons.

It invited pro-Western countries in the region to gin up internal or external "communist threats" as a simple way to procure U.S. aid without the necessity to negotiate agreements or treaties. Also, the policy was actually aimed at thwarting Nasser's ambitions to undermine his Middle Eastern rivals in the region, many of whom were pro-Western. The policy was given public shape, however, in a resolution that the Eisenhower Administration had pushed through Congress by the expediency of using the phrase "international communism." This left the Administration's actual policy in the dark and often at odds with its publicly expressed policy.

The practical result of this was State Department and CIA involvement, by covert means, in the complicated internal politics of the region, as the political winds within each country shifted. This created unintended and unwanted consequences for the United States, for which the CIA coined the term "blowback." Much of this activity, including coups and counter-coups, was inspired, influenced, or even orchestrated by the CIA. In Egypt, CIA operator Kermit Roosevelt, Jr. (Teddy's grandson), developed an exceedingly complicated and intimate relationship with (and sometimes against) the Nasser regime, as did CIA operative Miles Copeland. The U.S., however, acted for the rest of the decade under the conviction that Nasser himself was too powerful to be deposed and came to reconcile itself to containing his attempts to consolidate his influence with the other Arab states.

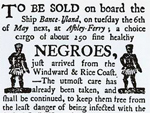

![[Stereograph], library of congress [Stereograph], library of congress](/sites/default/files/ad08001r.jpg)