The Many Faces of Immigration

Question

During the period from 1877 to 1925, what groups opposed immigration and who attempted to help immigrants?

Answer

“Immigration of some kind,” the historian John Higham has written, “is one of the constants of American history, called forth by the energies of capitalism and the attractions of regulated freedom.” This constancy did not preclude alternating periods of accelerating and waning nativism—a term understood best, Higham asserted, “as intense opposition to an internal minority on the ground of its foreign (i.e., ‘un-American’) connections.”

The half-century between the mid-1870s and the mid-1920s is a distinctive period in immigration history. As masses of immigrants arrived in the U.S. (nearly 24 million between 1880 and 1924), currents of intensifying nativism alternated with periods of decline until the spread of race-based nativism in the early 20th century led ultimately to the passage of legislation that severely restricted the numbers and types of immigrants entering legally. In charting the ebbs and flows of nativism, Higham’s classic study, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925, details two periods of national crisis: from 1886 to 1896, when immigration was linked with class conflict; and World War I, when cultural conformity became imperative to impose on immigrant groups who were viewed as threats to national unity.

During the first period of crisis, a number of groups sought restrictive immigration policies. Middle-class reformers and business leaders worried that polarization during a period of intense capital-labor strife threatened social stability; while native workingmen feared that immigrants competing for jobs would drive down wages. Most importantly for the future, “the amorphous, urban and semi-urban public,” consisting of “petty businessmen, nonunionized workers, and white-collar folk”—in Higham’s analysis, “rootless ‘in-betweeners’”—whose sense of danger grew into hysteria as increasing outbreaks of strikes and boycotts led them to identify immigrants with radicalism. Anti-immigrant hysteria flared up repeatedly throughout this period and afterward until restrictive legislation was ultimately enacted.

In eastern cities, anti-radical and anti-Catholic patriotic societies blamed immigrants for problems in schools and city government. The phenomenon spread nationwide when nativism arose in rural areas of the South and West. As new immigrants from southern and eastern Europe arrived in great numbers, patrician intellectuals and the Republican party, imbued with Anglo-Saxon ideology, pushed for restrictionist legislation. After Republicans won the 1896 election and the period of economic depression subsided, the national mood of crisis ebbed and the drive for restrictive legislation sputtered.

During the period of waning nativism that followed, progressives in the social settlement movement came to appreciate immigrants for values they might add to the national culture. Immigrant groups became influential forces in the Democratic and Republican parties. Politicians courted the immigrant vote, and with new immigrants comprising more than one third of the workforce in principal industries, corporate leaders shifted their stance and organized resistance to restrictive legislation.

At the same time, racially-based ideological beliefs gained force in other segments of society. Scientists promoted eugenics. Anti-Catholicism became an outlet for some former rural populists and progressives who blamed the Catholic Church when their hopes were not fulfilled. During the first quarter of the 20th century, racial nativism grew steadily in these segments.

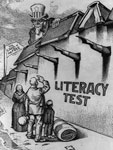

By 1914, the immigration restriction movement had strengthened in the South and West among the native-born working class and patrician intellectuals. On the West Coast, Japanese immigrants faced the same racial anxieties that infected attitudes toward Mediterranean and eastern European peoples in the east. However, restriction legislation failed to pass because the issue still was not felt deeply throughout the rest of the country, and strong opposition came from immigrant groups and big business organizations. Presidents Taft and Wilson vetoed literacy test bills, but in February 1917, Congress overrode the veto to enact the first law that prohibited immigration by adults unable to read.

During World War I, preparedness societies led the nativism movement. Simultaneously, an Americanization movement spread among churches, schools, fraternal orders, patriotic societies, civic organizations, chambers of commence, philanthropies, railroads, industries, and some trade unions with the goal of achieving a more tightly-knit nation through the assimilation of immigrants.

After the war and during the “Red Scare” that followed, the progressive ideal that America would steadily improve due to “immigrant gifts” lost credence. While immigrant groups actively continued to campaign against restrictive legislation, most of the other groups that had earlier opposed restriction now stood passively by as forces driven by anti-Semitism and anti-Catholicism, such as the Ku Klux Klan, intensified the “war-born urge for conformity.”

President Harding signed an initial immigration quota system into law in 1921. It marked, in Higham’s view, “the most important turning-point in American immigration policy.” Immigration quotas were established based on national origins: for each nationality, three percent of the number of foreign-born persons living in the U.S. in 1910 were allowed to enter the country. Passage of the law, Higham states, “meant that in a generation the foreign-born would cease to be a major factor in American history.” In 1924, a new law was enacted whereby quotas for each national group fell to two percent of the number of foreign-born living in the U.S. in 1890, a time when immigrant groups from southern and eastern Europe represented a much smaller percentage of the population than in 1910.

Higham’s critics have noted that his analysis in Strangers does not do justice to the situation of immigrants from Asia and Mexico. More recent scholarship (some of which is listed below) has investigated nativism with regard to these other groups of immigrants and relations amongst various immigrant groups. Newer studies also have focused more closely than Higham on the immigrant groups themselves and have examined immigration from comparative and global perspectives.

Bibliography

Barrett, James R., and David Roediger. “Inbetween Peoples: Race, Nationality and the ‘New Immigrants.” Journal of American Ethnic History 16 (Spring 1997): 3-44.

Barrett, James R., and David Roediger. “The Irish and the ‘Americanization’ of the ‘New Immigrants’ in the Streets and in the Churches of the Urban United States, 1900-1930.” Journal of American Ethnic History 24 (Summer 2005): 3-33.

Benton-Cohen, Katherine. “Other Immigrants: Mexicans and the Dillingham Commission of 1907-1911.” Journal of American Ethnic History 30 (Winter 2011): 33-57.

Bodnar, John. “Culture without Power: A Review of John Higham’s Strangers in the Land.” Journal of American Ethnic History 10 (Fall 1990-Winter 1991): 80-86.

________. The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985.

Gamio, Manuel. Mexican Immigration to the United States. New York: Arno Press and The New York Times, 1969.

Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, ed. Stephan Thernstrom. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1980.

Higham, John. “The Amplitude of Ethnic History: An American Story.” In Not Just Black and White: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Immigration, Race, and Ethnicity in the United States, ed. Nancy Foner and George M. Fredrickson, 61-81. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2004.

________. “Another Look at Nativism.” Catholic Historical Review 44 (June 1958): 147-58.

________. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925. 2nd ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1988.

Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876-1917. New York: Hill and Wang, 2000.

Lee, Erika. At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882-1943. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Martin, Susan F. A Nation of Immigrants. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Peck, Gunther. “Reinventing Free Labor: Immigrant Padrones and Contract Laborers in North America, 1885-1925.” In American Dreaming, Global Realities: Rethinking U.S. Immigration History, ed. Donna R. Gabaccia and Vicki L. Ruiz, 263-83. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

Roediger, David, and James Barrett. “Making New Immigrants ‘Inbetween’: Irish Hosts and White Panethnicity, 1890-1930.” In Not Just Black and White: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Immigration, Race, and Ethnicity in the United States, ed. Nancy Foner and George M. Fredrickson, 167-96. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2004.

Ueda, Reed. “Historical Patterns of Immigration Status and Incorporation in the United States.” In Gary Gerstle and John Mollenkopg, eds. E Pluribus Unum? Contemporary and Historical Perspectives on Immigrant Political Incorporation. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2001.

Ueda, Reed. “An Immigration Country of Assimilative Pluralism: Immigrant Reception and Absorption in American History.” In Klaus J. Bade and Myron Weiner, eds. Migration Past, Migration Future: Germany and the United States. Providence: Berghahn Books, 1997.