What is it?

A guided four-step reading process for primary documents that trains students to read a primary document like a historian. Use this guided process several times until students acquire the habit of reading and thinking like a historian.

Rationale

When historians read primary documents, they read at many different levels. They simultaneously pay attention to argument, purpose, context, content and credibility. Too often students will read a primary document as if it is a textbook. Students need to learn that reading a primary document is a different reading process and involves understanding the main point, but also contextualizing and asking skeptical questions about that point. Breaking the “reading” process into different steps helps students learn this.

Description

This is a teacher-led process that depends on transparency and discussion. In each step, the teacher clearly explains the purpose of that step, and uses questions to model how historians read primary documents. By doing so, the teacher shows students how to engage in the complex reading and thinking process that historians employ.

Teacher Preparation

- Choose a primary document that relates to the content you are teaching. If students already know some of the historical context when they read the primary document, they will be better able to think and read historically. (See Handout: Jackson Reading.)

- Read the primary document like a historian yourself. Make note of contextual clues (author, date, place, audience) and how those impact your understanding of the document. Underline the author’s main argument and supporting evidence. Make notes in the margins about the author’s purpose and the argument’s credibility. Write questions that you have about the document. With each of these steps, make a mental note of your reading and thinking processes so you can model these for students later. (See Example: Jackson Reading 4.) Be aware that you may need to conduct additional research to better understand the document’s historical context.

- Note characteristics of the document that will make it difficult for students to understand—for example, difficult vocabulary, obscure references, or confusing syntax. Consider using a vocabulary box at the bottom of the document or cutting sections of the document. (See this guide for help.) If there is a difficult section that is pivotal to the document’s meaning, mark it and review it with students in class as part of the discussion of the document.

In the Classroom

Introduce the activity

Give a copy of the primary document to each student. Explain that the class will learn how to read a primary document like a historian. Consider projecting the document on a screen so that you can model the kinds of observations that a historian makes and the kinds of questions she asks. The purpose is to show how historians consistently read at multiple levels.

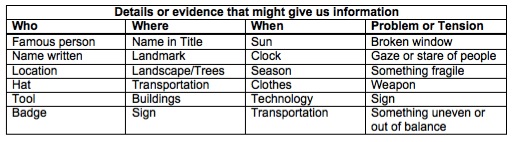

First Reading: Reading for Origins and Context

In this reading, ask students only to read the top of the document (where usually title, author, place, and date are provided) and the bottom of the document (where there may be additional information, in bibliographic notes, about the title, author, place, and date). For this read, students are not reading the main text of the document. The point here is to note and make some sense of the information about the document’s origins. Ask students to take note of each of the key sourcing elements. For each, they should ask themselves: Why does this matter? Why is the person significant? Why is the date or period significant? Why is the place significant? Why is the context significant? What background information do I know about any of these? (See Example: Jackson Reading 1.) Then ask students to identify what this context information suggests about the document. How does each part of the sourcing (person, place, date, context) impact how we read and understand this document? For more in-depth questioning on source materials, see here.

Second Reading: Reading for Meaning

In this reading, ask students to read the body of the text. They should read though the text to understand the author’s main idea and to get a sense of the document as whole. Ask students to underline only the sentence or phrase that best captures the author’s main idea. In this reading, students should skip over difficult vocabulary or sections. Too often students get stuck on a difficult or confusing section and stop reading or miss the big idea. The point here is to get the big idea of the document in order to make sense of more difficult or subtle parts later on. Once students have completed this reading, discuss students’ understanding of the big idea or meaning before moving ahead. If students have differing views about the big idea (and they usually do), ask different students to read aloud the sentence or section of the document they underlined. Discuss the merits and problems with each selection. Try to come to consensus about the big idea. Discerning the main argument is often difficult, but the process of wrestling with different claims is well worth it. (See Example: Jackson Reading 2.) Next, ask students what they notice about the document as a whole. In terms of genre, is it a persuasive speech, a private letter, or a newspaper article? In terms of content, is it clear or confusing? Were there many vocabulary words or historical references that students found difficult or skipped over? Who is the intended audience for the document? Discuss difficult passages or references. Often, when students get the main idea of a primary document, more difficult sections become easier to interpret. You might want to ask a student to read aloud a section that is particularly difficult and have the class work on interpreting it together in light of the main argument.

Third Reading: Reading for Argument

In this third reading, ask students to read through the body of the text again. This time students are reading to examine how the argument is constructed. What assertions, evidence, or examples are used to support or give credibility to the author’s argument? Students should underline any support (assertions, evidence, or examples) for the argument. Students should also write in the margins next to the underlined support. They should note whether they consider the support to be strong. Is it logical and believable? Does it contradict other evidence that the students have read? The point here is for students to see that most primary documents present arguments, and that arguments need to be understood and then interrogated for logic and credibility. Again, have a discussion with students. What are the supporting statements, and which supporting statements are strong? (See Example: Jackson Reading 3.)

Fourth Reading: Reading like a Historian

In this reading, ask students to go into the text one last time. This time students are bringing the earlier three readings together into a more complex final reading. Ask students to use the sourcing material (from their first read) to interrogate the argument and evidence (from the second and third reads). Students should write in the margins as they read to answer key questions. Given the author of the document, what bias or perspective might be expressed? How does that shape our understanding of the argument? Given the date of the document, what is the document responding to or in dialogue with? Given the place and audience of the document, how is the argument shaped to be effective? Like detectives, historians are suspicious. Their job is not to take the document at face value, but rather to dig deeper and use sourcing information to ask tough questions about the meaning of the document. Would the argument in the document have convinced its audience? Who might have disagreed or had a different perspective? What facts did the author leave out and why? What questions are unanswered by the document? Finally, historians evaluate primary documents. Is this primary document significant? Did it have an impact within its historical context? Did it express the view of an important group? How does it fit within debates taking place within that historical period? (See Example: Jackson Reading 4.)

Conclusion

Explain to students that they have now “read” a primary document like a historian. When historians read a primary document, they are constantly thinking about how their understanding of the argument or content is deepened by the sourcing information and historical context. Explain that as students become more experienced with primary documents, they too will become good historical detectives and be able to read at multiple levels. When a historian reads a primary document, a document becomes alive. The historian sees a primary document as part of a conversation or debate that took place within a specific historical context. The task for the sophisticated reader is to transform old, dead text into a live voice. Finally, ask students to list in their notebooks how a historian reads a primary document. Historians pay attention to sourcing information, select the main argument and support, look for credibility and bias, connect the text to the context, and ask questions like detectives. Note: Please see Four Reads handout for a short list of the four different reads.

Common Pitfalls

For teachers, this process takes time. You will need to dedicate a sustained block of time to teaching this approach. By dedicating time early in the year, students should be able to read primary documents more deeply over the rest of the year. For students, this process takes time. Too often students want to stop at the surface level of a document. With proper guidance, students should discover that there is a subversive pleasure in interrogating a document that is similar to interrogating an argument made by their parent or friend. Students should learn to use their natural skepticism to become historical detectives.