Free Speech Teaching Guide 1: The Birth of the Modern First Amendment and How Oliver Wendell Holmes Changed His Mind

This Teaching Guide is part of a series. Each of the four total teaching guides speaks to one aspect of the history of free speech. Although they work together to tell different parts of this history, it is not necessary to teach all of the guides or to teach them in a certain order. Each guide is a self-contained lesson.

(A PDF version of this teaching guide is also available for download-see left)

Other guides in the series:

Free Speech Teaching Guide 2: Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969): Defining and Arguing Hate Speech

Free Speech Teaching Guide 3: The Problem of National Security Secrets

Free Speech Teaching Guide 4: Mandel v. Kleindienst (1972): Censorship via Visa

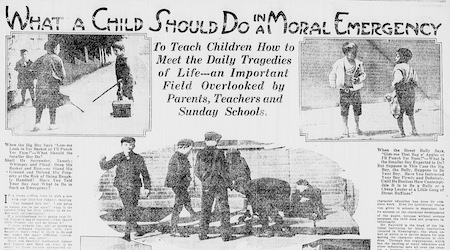

"Eugene V. Debs Making a Speech," c.1912-1918, Library of Congress

Recommended for:

- 11th Grade US History

- 12th Grade Government

- Undergraduate History

Table of Contents

Framing Essay:

This essay provides historical background on modern ideas about free speech and the First Amendment through analysis of two 1919 Supreme Court cases:

- Selection: Schenck v. United States 249 U.S. 47 (1919)

-

Selection: Abrams and others v. United States 250 U.S. 616 (1919)

Classroom Activities

Exercise 1: What does Freedom of Speech Mean? A guided reading of the Holmes opinion in Schenck v. United States 249 U.S. 47 (1919). Why did the Supreme Court decide it was acceptable to limit certain forms of speech?

Exercise 2: What Kinds of Speech are Protected? A full class group activity on the white board. What makes certain forms of speech so harmful that they fall outside First Amendment protection?

Exercise 3: Holmes Reconsiders. A detailed reading of Abrams and others v. United States 250 U.S. 616 (1919) and a comparison to Schenk. How might judges apply or avoid precedent?

Annotated Primary Sources

A section of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. majority opinion in the Schenck case.

A section of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. dissenting opinion in the Abrams case.

Homework Activity

Framing Essay

When I teach students the history of the First Amendment, the most basic thing I want them to learn is that the First Amendment has a history. Free speech seems like an enduring American value. After all, it is protected in the First Amendment to the constitution. But the idea that we should protect the "marketplace of ideas," that all sorts of speech should be protected from punishment, is barely more than a century old. In fact, its emergence can be traced to one year: 1919.

This guide focuses on the history of free speech in one crucial year (1919), exploring how one influential Supreme Court justice changed his mind about the value of antiwar speech and in the process wrote opinions that have shaped our attitudes to free speech ever since. It provides students an opportunity to see the First Amendment evolve at a crucial hinge in its history, and it also provides them an opportunity to think about how far the rights to free speech should extend during wartime.

During World War I, the US government sent critics of the war to jail. The Espionage Act of 1917 made it illegal to interfere with the draft, and government prosecutors successfully claimed that criticism of the war was a form of interference with the draft – if drafted soldiers thought the US should not be fighting the war, wouldn’t they be less likely to comply with the draft? On this theory, more than a thousand Americans were imprisoned for speech crimes. The most famous of them was Eugene Debs, the labor organizer and perennial Socialist presidential candidate, who was convicted for a Socialist stump speech in an Ohio park in the summer of 1918.

Find the text of the First Amendment Here

"Eugene V. Debs Making a Speech," c.1912-1918, Library of Congress

Eugene Debs Speaking in Canton, Ohio, c.1918, National Archives

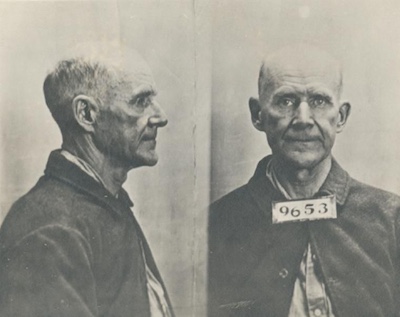

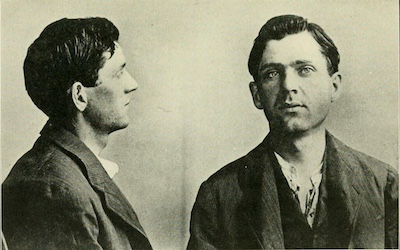

"Eugene Debs Mug Shot," c.1912-1929, New York Public Library

During class, I project the above images of Eugene Debs to force students to think about the human character at the center of this story. Debs was a noted orator, but we have no videos of him speaking.

We have to rely instead on photographs and the words of his audience, who described him as a captivating, moving speaker, who had the ability to make everyone in the crowd feel like he was addressing them directly.

Look Closer:

One technique Debs used was to lean out over the crowd – as you can see in the photo of his speech in Canton, Ohio.

You can find a transcript of Debs’ Canton Speech here: Eugene V. Debs' Canton Speech, 1918, Internet Archive

After the end of the war, in the Spring of 1919, the Supreme Court heard appeals from a number of the socialists prosecuted under the Espionage Act. The socialists claimed that the First Amendment protected their right to criticize the war. In unanimous decisions, the Supreme Court rejected their claims. During war time, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote for the court, it was perfectly acceptable for the government to criminalize speech that could interfere with the draft. The first classroom exercise will explore Holmes’s decision in this case: Schenck v. United States 249 U.S. 47.

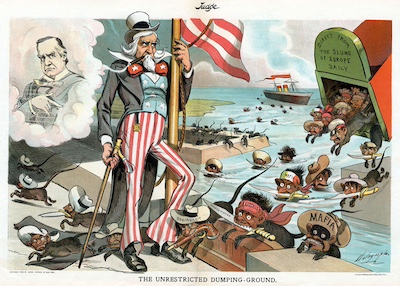

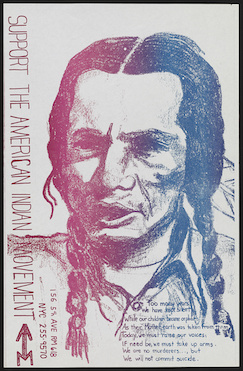

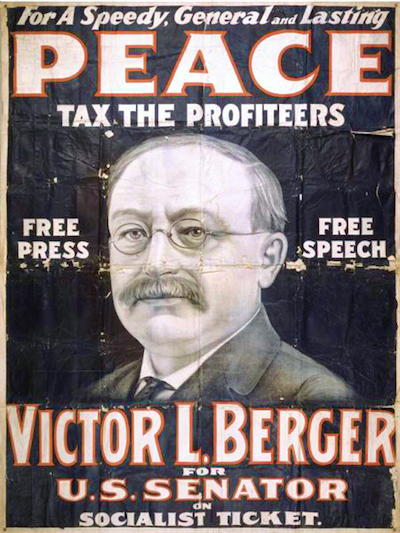

Victor L. Burger Campaign Poster, 1918, Wisconsin Historical Society

This campaign poster for Victor Berger reveals the centrality of free speech to the Socialist party and the connection between the right to free speech and opposition to the war.

Berger himself was prosecuted for speech crimes — a fascinating history that is well documented Wisconsin Historical Society site linked below.

Victor L. Berger Campaign Poster, 1918, Wisconsin Historical Society

Classroom Exercise I: What does Freedom of Speech Mean?

Contents:

Overview

Schenck WWI Anti-Draft Pamphlet, 1917

Excerpt of Schenck v. U.S.(1919)

Annotated excerpt of Schenck v. U.S. (1919)

Conclusion and Takeaways: What does free speech really mean?

Overview:

Holmes’ understanding of free speech was explained most clearly in the Schenck v. U.S. (1919) case, which concerned a pamphlet (pictured below) sent to drafted soldiers which encouraged them to protest the draft by writing to their congressional representatives.

It is useful to walk students through this excerpt from Holmes’ decision closely in class explaining the relevant steps of the logic. I do so by:

- Have students read the dense legal text of the Holmes’ decision out loud.

- Paraphrase and explain each sentence. My annotations provide the context and explanation I use. The following pages provide an annotated exploration of an excerpt of the Schenck decision.

Charles Schenck, WWI Anti-Draft Pamphlet, 1917, National Archives

Primary Source: Schenck v. U.S. (1919):

“It well may be that the prohibition of laws abridging the freedom of speech is not confined to previous restraints, although to prevent them may have been the main purpose, as intimated in Patterson v. Colorado, 205 U. S. 454, 462. We admit that in many places and in ordinary times the defendants in saying all that was said in the circular would have been within their constitutional rights. But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done. Aikens v. Wisconsin, 195 U.S. 194, 205, 206. The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing panic. It does not even protect a man from an injunction against uttering words that may have all the effect of force. Gompers v. Buck’s Stove & Range Co., 221 U. S. 418, 439. The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree. When a nation is at war many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right. It seems to be admitted that if an actual obstruction of the recruiting service were proved, liability for words that produced that effect might be enforced. The statute of 1917 in § 4 punishes conspiracies to obstruct as well as actual obstruction. If the act, (speaking or circulating a paper,) its tendency and the intent with which it is done are the same, we perceive no ground for saying that success alone warrants making the act a crime. Goldman v. United States, 245 U. S. 474, 477.”

For the Full Decision see: U.S. Reports: Schenck v.US 249 U.S. 47 (1919) Library of Congress.

Annotated excerpt of Schenck v. U.S.:

"It well may be that the prohibition of laws abridging the freedom of speech is not confined to previous restraints, although to prevent them may have been the main purpose, as intimated in Patterson v. Colorado, 205 U. S. 454, 462."

Previous or Prior Restraint:

- A particularly dangerous form of censorship because it prevents one from speaking at all without approval.

- In the 19th century, it was well understood that the First Amendment prevented this kind of licensing system - Holmes sees this as the "main purpose" of the First Amendment.

Patterson v. Colorado was a 1907 Supreme Court case in which a newspaper was punished for criticizing a court in Colorado. The newspaper claimed that the First Amendment protected their right to criticize the judiciary, but the Supreme Court ruled that it was acceptable to punish speech if it would interfere with the "course of justice." Holmes wrote the opinion for the court; two judges dissented.

Holmes cites this decision for two purposes:

- FIRST: in the sentence prior to the citation, he says that the main purpose of the First Amendment is to prevent the establishment of a censorship board that can approve or deny the right to speak or publish before one has spoken.

- The question at stake was whether the First Amendment also protected you from punishment after you have spoken.

- Holmes here begins by conceding that the First Amendment might offer some protections to post-speech punishment - it is not only limited to a ban on prior restraint.

- SECOND: the implication is that the First Amendment offers fewer protections against post-speech punishment than it does against prior restraint.

“We admit that in many places and in ordinary times the defendants ... circumstances in which it is done. Aikens v. Wisconsin, 195 U.S. 194, 205–206 (Volume, Publication Name, Page Numbers)...

This is an opportunity to explain to students how to read Supreme Court decisions. The citation of cases, followed by the numbers, is placed in the text which will be new to many students.

The citation is the equivalent of a footnote or parenthetical reference. If you just want to read the substance of the opinion, students can jump over the citation, which will make the opinion easier to follow. I often explain to students, familiar with finding material online, how bound volumes of cases look on library shelves, and why such a reference system is helpful.

Holmes cites an opinion from a 1904 case about unfair trade practices. The Aikens case established that the decision to sign or not sign a business contract might be protected in some cases, but not if it is part of a criminal conspiracy to harm a competitor.

The details are not directly relevant to the speech context; he is citing the case to support the abstract proposition that acts which can be constitutionally protected in some cases may not be constitutionally protected in different contexts.

In Schenck - the right to say what was said in the pamphlet might be protected in some contexts, but that doesn't resolve the question of whether it is in this case.

"The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing panic.”

- This is a famous metaphor. But how does it work in this case?

- Holmes is arguing that you do not have a right to falsely shout fire in a theater - this will cause a panic, a harm which societies would reasonably want to prevent.

- But it matters that he assumes that the shout of "fire" is false - if there actually was a fire in the theater, you definitely want someone to yell!

- The metaphor seems to have been introduced into case history by the federal lawyer prosecuting Eugene Debs. When Debs's lawyers claimed a right to free speech, the prosecutor said that this was the same thing as claiming the right to "go into a crowded theater...and yell 'fire' when there was no fire and people [would be] trampled to death."

- It seems likely that the prosecutor was thinking of a recent incident in Calumet, Michigan, where striking copper workers had organized a children's Christmas party on the second floor of a hall in 1913. During the party, someone yelled fire, and there was a stampede which killed 73 people. It made the front-page of the New York Times and entered the political culture. Woody Guthrie's 1939 ballad “1913 Massacre" is about the event - and captures the assumption by left-wing Americans that the false shout of fire had come from an anti-union vigilante.

- If this is the origin of Holmes' metaphor, it is deeply ironic that the socialists in these World War I cases were being accused of a "false shout of fire."

Questions for Students:

Is it fair to compare Schenck’s pamphlet to a false shout of fire?

Is the harm of the pamphlet as immediate as a stampede?

Is the pamphlet ‘false’ in the same way as the shout in the theater?

If the alarmist shout about the draft is the equivalent of a true fire, might there be benefit in hearing it?

What might the merits be of debating the pamphlet, even if it is difficult to establish whether or not it is true?

Why might Holmes have chosen this metaphor?

Why do courts use analogy, metaphors, and comparisons in their decisions?

Find the song here: Woody Guthrie, “1913 Massacre,” Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

“It does not even protect a man from an injunction against uttering words that may have all the effect of force. Gompers v. Buck’s Stove & Range Co., 221 U. S. 418, 439. The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree. When a nation is at war many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right. It seems to be admitted that if an actual obstruction of the recruiting service were proved, liability for words that produced that effect might be enforced.”

- Samuel Gompers was a union leader organizing a consumer boycott of Buck’s Stove, an anti-union company. A court ruled that this kind of boycott was an illegal interference with commerce, and Gompers claimed that the ban violated his rights to free speech.

- In 1911, the Supreme Court rejected the claim, saying Gompers’ speech was a "verbal act...exceeding any possible right of speech which a single individual might have."

- Here, Holmes is saying that it is possible to consider Schenck's pamphlet in the same way - as a verbal act which has such effects in the world that they should be treated as acts, not as part of freedom of speech.

- Holmes here assumes that constitutional rights during wartime are different, and this is crucial to his decision. This is a useful place to discuss with students whether they agree.

Questions for Students:

- What constitutes a “war”?

- US fought the Vietnam War, for instance, without a formal declaration of war.

- If the right to free speech should be limited during wartime, how do we define a war?

- Does a national security emergency count, or only when congress formally declares war?

- For a useful discussion of the ambiguities of the legal term "wartime," see Mary L. Dudziak, Wartime: An Idea, Its History, Its Consequences. (Oxford, 2012).

“The statute of 1917 in § 4 punishes conspiracies to obstruct as well as actual obstruction. If the act, (speaking or circulating a paper,) its tendency and the intent with which it is done are the same, we perceive no ground for saying that success, alone warrants making the act a crime. Goldman v. United States, 245 U. S. 474, 477.”

- Goldman was a case from 1918 about a conspiracy to interfere with the draft - it cited "settled doctrine" that conspiring to do an illegal act is a crime whether or not it is successful.

- This is another citation similar to Aikens. Students don't need to know the details of the case to grasp the general point: for certain crimes we punish attempts as well as successes. Attempted murder is the most obvious example.

- In some of his earlier writings on the law, Holmes had explained that we punish attempts as well as successes because we want to prevent certain dangerous outcomes - "the danger becomes so great that the law steps in" See G. Edward White, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes: Law and the Inner Self, 261-262.

Conclusion and Takeaways:

- To modern eyes, the decision seems to make a mockery of the First Amendment.

- If you can be jailed for telling people to write to their congressional representatives, what does freedom of speech even mean?

- But Holmes’ decision reflected prevailing understandings of the First Amendment. Throughout the nineteenth century, it was understood that freedom of speech had limits – that there were some sorts of speech acts – such as obscenity, or certain forms of criticism of public officials – that fell outside the protection of the First Amendment.

- In his influential 1833 treatise on Constitutional law, the Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story put it like this: “that this amendment was intended to secure to every citizen an absolute right to speak, or write, or print, whatever he might please, without any responsibility, public or private therefore, is a supposition too wild to be indulged by any rational man.” “Freedom of speech” didn’t mean you could say anything at all, with no consequences. Speakers could be held responsible—could be punished—for speech acts that went beyond the pale.

- The amendment being referred to here is the First.

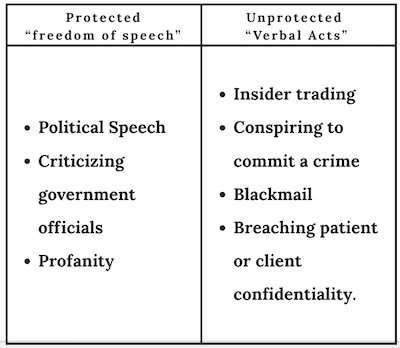

- Even today, in fact, we still criminalize some sorts of speech which we believe to be outside of the “freedom of speech”: no-one can claim First Amendment rights to insider trading, to conspiring to commit a crime, to blackmail, to breaching patient or client confidentiality.

Classroom Exercise 2: What Types of Speech are Protected?

Contents

Overview

Group Activity Directions

Group Activity Example

Overview:

To help students grasp the nuances of free speech, I often do a classroom exercise exploring the differences between speech-acts which are considered protected parts of freedom of speech and which are considered verbal acts not warranting protection. After completing the exercises below, students should be able to better grasp the following ideas:

- In the spring of 1919, Holmes was simply saying that war criticism was a sort of speech that fell outside the meaning of “freedom of speech” under the First Amendment.

- Speech that created a “clear and present” danger to the war effort could be regulated – and criticism of the war effort created such a danger.

- Eugene Debs' appeal was denied along with that of Schenck He ran for president in the 1920 election from jail, where he received 913,000 votes.

- But the legal meaning of free speech did not end with Schenck and Debs. As we will see in the final exercise (and additional teaching guides in this series), classifications of free speech would continue to be debated throughout the rest of the twentieth century.

Group Activity Directions:

- Step 1:

- Use the language from the Gompers decision to create two categories on the board: speech protected by “freedom of speech” and “verbal acts” that are unprotected. It might be helpful to explain that this means that simply because words are used is not enough to make it “Speech” that is protected under the First Amendment.

- Step 2:

- Ask students to name some sorts of speech that are protected by the First Amendment. Depending on their level of awareness, it is normally not too hard to generate a few examples: political speech; criticizing a government official; profanity; and so forth. This should only take a minute – you just want a few examples.

- Step 3:

- Ask students what types of verbal acts can they think of that are not protected by free speech? They often struggle for a while, naming hard cases but ones implicated by free speech rights – for instance, pornography. You can put these in the middle of the two categories, as you can for anything you are not sure of. But some sorts of speech are clearly just verbal acts that raise no First Amendment concerns- insider trading, conspiring to commit a crime, blackmail, breaching patient or client confidentiality. If students are struggling, I give them one (insider trading) and see if they can come up with others. It normally only takes about 5 minutes or so, but it usually produces a fairly animated discussion, and helps clarify the conceptual issue by having students practice applying it.

- Step 4:

- After outlining the two categories, ask the students where Holmes was putting Schenck’s pamphlet. This one has a correct answer: He was saying it wasn’t like a piece of political speech; it was an act of interfering with the draft – one that just happened to be verbal, to take the form of speech – that could be regulated.

Classroom Exercise 3: Holmes Reconsiders

Content:

Overview & Primary Source: Abrams Pamphlet

Context

Holmes' Dissent Annotated

Group Questions

Conclusions and Key Takeaways

Overview:

If desired, you could assign the Abrams Pamphlet or the case dissent as homework reading. First, review the Context for yourself, then break students into groups for the activity.

- Have students read the Abrams dissent if they have not already.

- Have groups discuss the questions listed in the annotation.

- Provide students with information in the Context and Conclusion

Jacob Abrams Pamphlet and Transcript

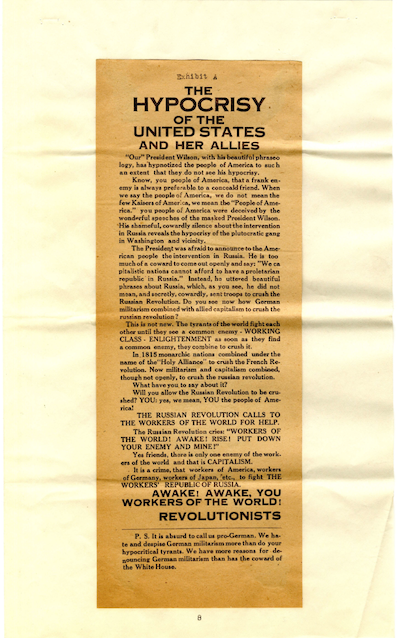

“The Hypocrisy of the United States and her Allies,” August 1918, National Archives.

"THE HYPOCRISY OF THE UNITED STATES AND HER ALLIES

“Our” President Wilson, with his beautiful phraseology, has hypnotized the people of America to such an extent that they do not see his hypocrisy.

Know, you people of America, that a frank enemy is always preferable to a concealed friend. When we say the people of America, we do not mean the few Kaisers of America, we mean the “People of America.” You people of America were deceived by the wonderful speeches of the masked President Wilson. His shameful, cowardly silence about the intervention in Russia reveals the hypocrisy of the plutocratic gang in Washington and vicinity.

The President was afraid to announce to the American people the intervention in Russia. He is too much of a coward to come out openly and say: “We capitalistic nations cannot afford to have a proletarian republic in Russia.” Instead, he uttered beautiful phrases about Russia, which, as you see, he did not mean, and secretly, cowardly, sent troops to crush the Russian Revolution. Do you see now how German militarism combined with allied capitalism to crush the Russian revolution?

This is not new. The tyrants of the world fight each other until they see a common enemy — WORKING CLASS — ENLIGHTENMENT as soon as they find a common enemy, they combine to crush it.

In 1815 monarchic nations combined under the name of the “Holy Alliance” to crush the French Revolution. Now militarism and capitalism combined, though not openly, to crush the Russian revolution. What have you to say about it?

Will you allow the Russian Revolution to be crushed? YOU: yes, we mean, YOU the people of America!

THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION CALLS TO THE WORKERS OF THE WORLD FOR HELP.

The Russian Revolution cries: “WORKERS OF THE WORLD! AWAKE! RISE! PUT DOWN YOUR ENEMY AND MINE!”

Yes friends, there is only one enemy of the workers of the world and that is CAPITALISM.

It is a crime, that workers of America, workers of Germany, workers of Japan, etc., to fight THE WORKERS’ REPUBLIC OF RUSSIA.

AWAKE! AWAKE, YOU WORKERS OF THE WORLD! REVOLUTIONISTS

P.S. It is absurd to call us pro-German. We hate and despise German militarism more than do your hypocritical tyrants. We have more reasons for denouncing German militarism than has the coward of the White House."

“The Hypocrisy of the United States and her Allies,” August 1918, National Archives

Context

- In the fall of 1919, six months after the Schenck decision, another group of radicals appealed their conviction for wartime dissent. This time, the case concerned anarchists who had distributed a pamphlet calling for a general strike in New York City in an effort to prevent the production of war materials. They had been charged under a different section of the Espionage Act, one which made it illegal to interfere with wartime production.

- In the Abrams case, seven of the justices simply applied the Schenck precedent from the spring and dismissed their appeal. As your class discussion might reveal, that seems sensible enough—if it had been illegal to advocate writing to a congressman, then calling for a general strike seemed even more of a “clear and present danger.”

- But then Holmes did a surprising thing. Rather than applying his own precedent from only six months prior, he dissented – arguing that the anarchists had a First Amendment right to call for a general strike. What had happened?

- Over the summer, Holmes’ decisions in the Schenck and Debs cases had been criticized by a newly emerging group of free speech advocates – intellectuals, lawyers and journalists that Holmes respected, and who were often friends. In particular, Harold Laski, a British-born academic teaching at Harvard and a close confidant of Holmes, waged a subtle influence campaign: sending Holmes reading material on the history and philosophy of free speech; arranging for Holmes to meet with a Harvard Law professor who had criticized the Debs decision. At the same time, Laski and other friends of Holmes at Harvard faced their own free speech crisis – they had spoken out in support of a strike of Boston police in 1919, and many were calling for them to be fired from the university.

- These experiences changed Holmes’ mind about the value of free speech, and his dissent in Abrams reflected this new understanding.

Holmes' Dissent Annotated:

Abrams v. U.S. Dissent

“Persecution for the expressions of opinions seems to me perfectly logical. If you have no doubt of your premises or your power and want a certain result with all your heart you naturally express your wishes in law and sweep away all opposition. To allow opposition by speech seems to indicate that you think the speech impotent, as when a man says that he has squared the circle, or that you do not care whole-heartedly for the result, or that you doubt either your power or your premises. But when men have realized that time has upset many faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas-that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out. That at any rate is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment. Every year if not every day we have to wager our salvation upon some prophecy based upon imperfect knowledge. While that experiment is part of our system I think that we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe and believe to be fraught with death, unless they so imminently threaten immediate interference with the lawful and pressing purposes of the law that an immediate check is required to save the country."

- The first thing to point to in this passage is that Holmes is not citing any cases. This is a sign that he is thinking more philosophically about what free speech should mean; and also that he is venturing into new territory, not covered by previous cases.

- Classroom Discussion (Advanced Classes):

- Does the role of judges only apply to already-existing law when deciding cases?

- Or are judges creating law when they judge particular cases?

- "If you have no doubt of your premises or your power and want a certain result with all your heart you naturally express your wishes in law and sweep away all opposition."

- This sentence more or less sums up the approach Holmes took in the Schenck case six months prior - if you want to stop interference with the draft, why not ban speech that seeks to interfere with the draft?

- "...ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas-..."

- This is a crucial passage in the history of the First Amendment, where Holmes introduces the idea that there is a "Free trade in ideas" and that the best test of truth is whether it succeeds in the "competition of the market." While he doesn't use the exact phrase, this would come to be known as the "marketplace of ideas" - and the idea is closely related to his relativistic theory of truth: there are no guarantees that you can realize absolute truths, but the best method is to let all ideas be expressed, and see which becomes the most popular.

- It is ironic that this defense of the free speech rights of radical socialists and anarchists is expressed in the language of the free market - for they were critics of the market. But Holmes had translated their calls for free speech into his own language, influenced by his reading of 19th century liberal philosophy.

- "That at any rate is the theory of our Constitution..."

- Holmes here warns us that there is no promise that truth will emerge from the competition of the market - you can't be sure that the best or most correct ideas will catch on.

- But what it means to live in the American democracy, he says, is that you have to believe in that process of experimentation and trial and error, and that public opinion - even if based on imperfect knowledge - should be the guide to determining what is correct.

- If it is true that the democratic experiment relies on the free formation of public opinion, Holmes suggests, then it is a dangerous thing to let governments block any expressions of opinion, even those we hate.

Compare Frameworks: Schenck & Abrams

Schenck:

- Holmes says it is legitimate to police speech that might cause something you believe to be an evil.

Abrams:

- Holmes warns against such censorship.

- Censorship should be allowed only when it threatens "imminent" and "immediate" interference with a "pressing purpose."

Find the Abrams dissent here: Abrams v. United States (1919), National Constitution Center

Group Questions:

- Is the harm to the war effort here more or less severe than that in Schenck?

- In Schenck, the pamphlet asked people to write to their congresspeople to protest the draft; here the pamphlet calls for a general strike. Students should be able to see that a general strike would interfere with production more directly than a criticism of the war would interfere with the draft.

- Is the danger more "clear and present" in Abrams or Schenck?

- Arguably, throwing leaflets out to workers is more direct than mailing them to soldiers or speaking to a picnic – you are directly addressing the audience you want to act, and asking them to act soon.

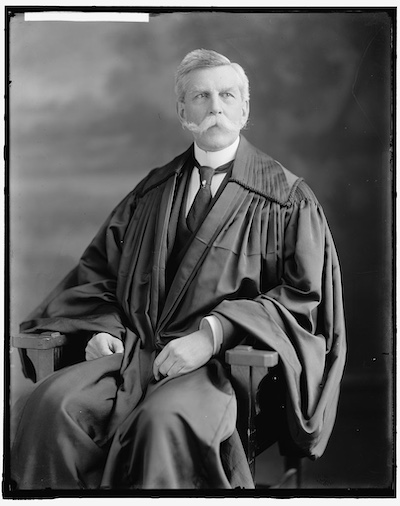

“Holmes, Oliver W. Justice,” c. 1905-1945, Library of Congress

Conclusions and Key Takeaways:

- Holmes was not a radical, and he had no sympathy for the anarchists at the heart of the case – he thought they were advocating a “creed of ignorance and immaturity.” But he had come to believe that it was important to democracy to protect their rights to speech.

- In the short-term, of course, that didn’t matter to the defendants in Abrams. A dissent doesn’t have any impact on the outcome of the case, which is determined by the majority decision – the anarchists were sent to jail, and later deported, for their pamphlet. But a dissenting opinion in a Supreme Court case also creates a record of the fact that some Justices disagreed with the opinion of the majority – and Holmes’s dissent in Abrams would become so famous and influential that it would end up becoming the legal consensus.

- Over the twentieth century, Holmes’ dissent would guide the development of First Amendment law and philosophy, playing a crucial role in the rise of our contemporary right to free speech. Following from Holmes’ Abrams dissent, Americans today tend to speak of a “marketplace of ideas,” in which there is value to hearing from a diverse range of voices, even if you disagree with them, even if you think they might cause some harm you would prefer to avoid. But it wasn’t inevitable that this would be the way Americans came to think about the First Amendment.

- It came out of a particular moment of history – the clashes between socialists and the government in World War I, the police strike at Harvard, and the influence of a small group of civil libertarians seeking to change the mind of one Supreme Court justice.

Optional Classroom or Homework Exercise:

- Ask students to identify a sort of speech today that they believe could be treated as a “verbal act” outside of the protection of the First Amendment.

- Ask them to make two arguments, one on either side of the question:

- If they had to make the case that it creates a “clear and present danger,” how would they do so?

- What are the benefits of protecting that speech as part of the marketplace of ideas?

Remember: The goal here is not for students to necessarily decide on a complicated question, nor to correctly understand the current state of First Amendment law on these issues, but to practice applying the two different visions of free speech implicit in the Schenck decision and the Abrams dissent – one which focuses on regulating harms, the other on the democratic value of hearing all speech.