Andrew Johnson, the 17th president of the United States, became the first to be impeached when the House of Representatives on February 24, 1868, overwhelmingly passed an impeachment resolution and in the next few days approved 11 articles of impeachment for the Senate to consider. Following an 11-week trial, the Senate vote for conviction fell one short of the two thirds required by the Constitution to remove a president from office. That failure, some historians believe, may have had an adverse impact on the fate of Congressional Reconstruction and influenced the orientation of the Republican Party.

Johnson, a member of the Democratic Party, and the Republicans who controlled Congress differed greatly concerning Reconstruction. Johnson wanted the South to remain, in the words of his biographer, historian Hans L. Trefousse, a “white man's country,” while Republicans believed that blacks deserved civil rights. Through its Reconstruction legislation, Congress had empowered the army to carry out its policies in the South, but Johnson, as the army's commander-in-chief, had obstinately blocked their execution.

Factions within the Republican Party itself differed concerning Reconstruction policies. Radical Republicans, many of whom had been leaders of the abolition movement, envisioned Reconstruction as inaugurating fundamental change. Their ideology, as Eric Foner has written, “was the utopian vision of a nation whose citizens enjoyed equality of civil and political rights, secured by a powerful and beneficent national state.” Radicals believed that blacks should have the same opportunities for employment as whites and some supported land confiscation of the South’s ruling class in order to grant homesteads to former slaves. Mainstream Republicans opposed confiscation and feared policies that might lead to inflation and inhibit economic growth. They generally favored fiscal responsibility and the establishment of a coalition between “enlightened planters, urban business interests, and black voters, with white propertied elements firmly in control,” Foner asserts.

Radical Republicans, many of whom had been leaders of the abolition movement, envisioned Reconstruction as inaugurating fundamental change.

Although radicals began to talk of impeachment as early as October 1865, moderates in the party agreed to use it only as a last resort after their efforts at Reconstruction had been stymied repeatedly by the president's resistance and Democrats had achieved key victories in 1867 elections. Moderates joined radicals in their belief that the Democrats would gain the presidency in 1868 if Reconstruction was not successfully achieved. Trefousse contends, “A majority of the Republican party had become convinced that Reconstruction could not be completed successfully as long as Johnson occupied the White House.”

Yet impeachment carried with it grave risks for the Republicans. Its failure “would be interpreted as a stunning defeat for radicalism,” Trefousse writes. “Reaction would be revived in the South, and the foes of Reconstruction would be reassured and strengthened.” Trefousse views the failure to predict this outcome as “one of the greatest mistakes the radicals made.”

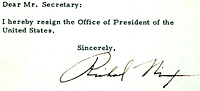

The specific impeachment charges drawn up by moderates in the House dealt for the most part with Johnson's removal from office of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, an act allegedly in violation of the Tenure of Office Act that Congress had passed to keep Johnson from dismissing underlings without Senate approval. Whether the law applied to Stanton, an ally of the Congressional Reconstruction effort, was debatable, however. Seven moderate Republican senators voted for acquittal after deals were made with Johnson to ensure that he would not interfere with Congressional Reconstruction and would appoint a new secretary of war agreeable to the moderates.

Mainstream Republicans opposed confiscation and feared policies that might lead to inflation and inhibit economic growth.

In the short term, Congressional Reconstruction did not seem to be affected adversely by Johnson's acquittal. Most of the new state governments in the South were controlled by Republicans, the Fifteenth Amendment was passed and ratified, and blacks were elected to federal, state, and local offices. Trefousse contends, however, that the acquittal offered “a tremendous moral boost for the conservatives” and “demoralized the radicals.” Moderates subsequently gained power within the Republican party, and during the 1868 convention nominated Ulysses S. Grant over Benjamin F. Wade, the congressman who had been in line to become president had Johnson been impeached and an ally of the radicals.

Reconstruction's success in the long run, Trefousse asserts, was impossible without strong presidential support to stop reaction from setting in. “Had Johnson not been as persistent and had the impeachment succeeded,” he concludes, “it is conceivable that the outcome might have been different.” Johnson's latest biographer, Annette Gordon-Reed, concurs with Trefousse, quoting his statement that as a result of the acquittal, Johnson “preserved the South as a white man's country.”

Some reviewers of Trefousse’s monograph on the impeachment have taken issue with his conclusion. Michael Perman criticizes Trefousse for “grossly exaggerating Johnson's impact by suggesting . . . . that his acquittal helped Alabama Conservatives return to power six years later in 1874.” Richard H. Sewell contends that “recent studies . . . . , make it appear doubtful that ‘a real social revolution in the South would have occurred in these years whatever Johnson might have done.”

![Photo, [Andrew Johnson, half-length portrait, facing left], 1865-1880, A. Bogardus, Library of Congress Photo, [Andrew Johnson, half-length portrait. . . ], 1865-1880, A. Bogardus, LoC](/sites/default/files/andrewjohnsonand113x150.jpg)