Overview

The New York Public Library offers a digital gallery of many photographs and artifacts from its collections. The NYPL–Digital Gallery features a searchable index of thousands of pictures and artifacts related to a wide variety of subjects in American history. Best of all it is free and easy to use.

How to Find What You’re Looking For

Next time you are looking for a photograph of an important historical figure, try using the NYPL-Digital Gallery to search for images of him/her. A simple search in the NYPL search engine box on the home page can unearth thought-provoking photographs, like this candid shot of President Grover Cleveland. This image says a lot more than the images one would obtain from a basic Internet image search.

Also from the home page, try browsing by subject and look for documents related to your state. There are many great images that capture towns and cities in the past. This is a fantastic way to tie in local history. On a digital map, instruct students to locate where an old building once stood using a site like WhatWasThere.com. Students could also compare this detailed 1911 collection of photos of 5th Avenue to a Google Maps street view of 5th Avenue today to show students the impact of urbanization.

The NYPL-Digital Gallery can also help locate sources that might display social change over time. For instance, you might find pictures showing how bridal fashion has changed over time. If you click ‘Browse Sources’ and type “brides” into the ‘Explore Subjects’ search box, you will see a link to pictures tagged by this subject from 1400 through 1939.

Instructional Ideas

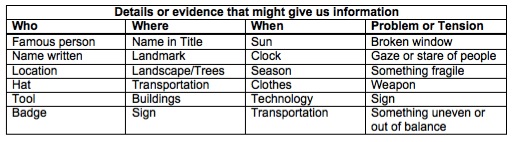

One of the skills we want to teach history students is how to ask the right questions. A way to practice this might be with the use of interesting images, like this one, of a “courting stick” in action. This photo begs students to ask many questions. A courting stick is a long, hollow tube around six feet long with a mouthpiece at each end. It allows courting couples to discreetly speak with one another while maintaining the appropriate physical boundaries. If you simply browse the depths of the NYPL-Digital Gallery for 10 minutes, you are bound to stumble across a treasure like this that will capture your students’ historical curiosity.

Another idea is to have students create a digital timeline incorporating images found in the Digital Gallery to demonstrate the concept of change over time. This assignment asks students to analyze changing American culture. Students could use the subject search feature of the Digital Gallery to find images related to sports, weddings, leisure, and other cultural phenomena in America over the last 250 years.

Allow yourself an opportunity to explore this vast collection of primary sources for use in your classroom. Give your students time to investigate the Digital Gallery as well. After all, this is one way historians craft questions about the past. In my browsing, I stumbled across this revealing group of photos related to African Americans serving in World War II. The photos capture the many ways African American men and women served during the war.

The NYPL-Digital Gallery is a one-stop-shop for primary sources on every topic in American history, and it is organized in a logical way, making it easy to collect documents and images.

The NYPL-Digital Gallery is a one-stop-shop for primary sources on every topic in American history, and it is organized in a logical way, making it easy to collect documents and images. As you search for images you may want to create a collection of images for a class. You will note, above each image is a button to “select” the image. By selecting a picture it is stored in “My Collection,” accessible from the home page and from the menu bar at the top of each page. This function is handy when building a lesson around a group of documents. As you find new ways to use the NYPL-Digital Gallery I hope you will share them with us here.