Daily Objects, 19th-century America

Video One

- Erastus Salisbury Field, American, 1805-1900, Joseph Moore and His Family, c. 1839, oil on canvas, 109.23 x 237.17 cm (82 3/8 x 93 3/8 in.), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Maxim Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815-1865, 58.25, Term of use: Life of project, Photograph copyright 2009 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Lambert Hitchcock (American, 1795-1852), Side Chair, 1826-1829, Mixed hardwoods, paint, and rush, 33 x 17 3/4 x 20 in. (83.8 x 45.1 x 50.8 cm), Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of Lucy D. Hale, 1990.28.2.

Video Two

- Erastus Salisbury Field, American, 1805-1900, Joseph Moore and His Family, about 1839, oil on canvas, 109.23 x 237.17 cm (82 3/8 x 93 3/8 in.), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Maxim Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815-1865, 58.25, Term of use: Life of project, Photograph copyright 2009 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Looking glass, American, about 1830-40, Object Place: Connecticut Valley, United States, Mahogany, gilt; glass, H: 37 5/8 in., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Maxim Karolik, RES.58.3, Term of use: Life of project, Photograph copyright 2009 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Tie pin, about 1830-40, Object Place: New England, United States, Gold and black enamel, hair, Overall: 2.2 cm (7/8 in.), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Maxim Karolik, RES.58.5, Term of use: Life of project, Photograph copyright 2009 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Buckle, about 1830-1840, Object Place: Massachusetts, United States, Mother-of-pearl, Overall: 8.3 cm (3 1/4 in.), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Maxim Karolik, RES.58.7, Term of use: Life of project, Photograph copyright 2009 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Brooch, about 1830-50, Object Place: New England, United States, Gold, stone, Overall: 1.9 cm (3/4 in.), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Maxim Karolik, RES.58.6, Term of use: Life of project, Photograph copyright 2009 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Video Three

- "Across the Continent: Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way"; lithograph; hand colored; Currier and Ives (publisher); Ives, J.M. (lithographer); Palmer, F. (Fanny), 1812-1876 (artist), BANC PIC 1963.002: 1530-D. Courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

- The Parley, 1903 (oil on canvas), Remington, Frederic (1861-1909) / Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas, USA / Hogg Brothers Collection, Gift of Miss Ima Hogg / The Bridgeman Art Library International.

- Cottone Auctions

- Country Home

- Federalist Antiques

- Hitchcock Chair Company

- Larry Miller, Flickr

- Library of Congress

- Minneapolis Institute of Arts

- National Archives and Records Administration

- New Jersey State Museum

- Producer's Blog: Currier & Ives

- Project Gutenberg

- Style in the Heartland

- University of Virginia

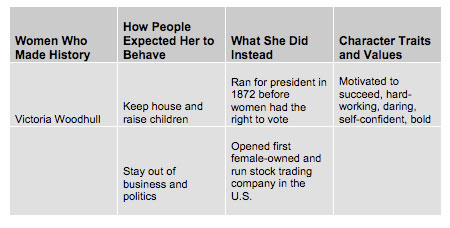

Historian David Jaffee analyzes three 19th-century objects (a Hitchcock chair, a family portrait, and a lithograph of the West), discussing how they were made, how they were used, and what they can tell us about the past. Jaffee models several historical thinking skills, including:

- (1) Close reading of the portrait and the lithograph, paying attention to symbols, objects, and other visual clues to understand the images.

- (2) Attention to key source information, such as the date and artist of the lithograph to highlight the significance of its portrayal of the west through the eyes of easterners.

- (3) Contrasting the Hitchcock chair as a manufactured object with its use in the portrait as a carefully selected symbol of the family’s wealth and possessions.

- (4) Examining the larger context of all three objects to connect them with economic, cultural, and social change.

This is a side chair, meaning it's not an armchair. Doesn't have arms. Much more interestingly, it's a Hitchcock chair. Now, Hitchcock chairs are both known as chairs that were made by the Hitchcock Company or Lambert Hitchcock initially, the entrepreneur in Connecticut. But more significantly they're a certain genre of chair. So lots of different painted chairs of the first half of the 19th century, sort of festooned with lots of cornucopia and sort of gold stenciling, cane seats, were known as Hitchcock chairs. So it's got a larger sort of import because of that.

But it's extremely popular. You can still find lots of these in antique shops.

What I find really interesting about it first of all, is the decoration. And I think that's what it was meant to say. It's a decorated chair, not just a plain, black chair.

What I know from my own prior knowledge of course, is that often painted decoration stands in for sort of other kinds of decoration. In earlier chairs, one would have used rich carving, which takes a lot of experience by the artisan. So here, instead of having rich depth in the carving, we have two things which stand in for that three-dimensionality. We have turnings. This is done on a lathe. These are done—also mass-produced, so that these parts are relatively interchangeable.

So at the same time as these Hitchcock chairs were being mass produced, $1.50 a piece, usually sold in sets, someone like Eli Terry in the Connecticut clock industry is also making cheap shelf clocks by relatively interchangeable parts, so that the gears in the clocks are made all at once and they can be fit into a variety of different clocks. So that obviously is going to cut down on cost.

And also on the skill level for the chair workers assembling the chair. So, much of the work is really done by semi-skilled workers rather than an older style where one person made one chair at a time.

In some chair industries they would have made some parts at the sawmill. They would have then made other parts or assembled them in a shop. And then third, they would have had women and children seating the chairs by hand in homes. And then collected everything together.

So, in the case of Hitchcock's innovation, sort of like the Lowell Mills, is that he did everything together in a factory, which really allowed him great advances in terms of scale—savings by scale.

When you look at the back, on the back of the seat it will say, "Hitchcock warranted." And so it's got a stencil on the back—this is the first entrepreneur to do this—so that they're sort of warranted that if, you know, there's a problem with this, you can sort of return them.

So again it's this assumption, and this is a new stage, that these will be distributed throughout the United States. There will not be a face-to-face encounter between maker and consumer, so that you would need to have this sort of publicized warranty in a way that if you actually knew the craftsman 20 years earlier you wouldn't need that sort of published, stamped warranty.

So what Hitchcock's great idea was to take a bit of this and a bit of that, put it together, push it forward with division of labor, and also extensive marketing, and really produce something that's a prototype of a sort of mass-produced object that bespeaks gentility to a wide section of the American public from top to bottom, and do it at a really low price. And that really is what accounts for the popularity of the chair at the time, and I think also its significance for us to sort of look at and talk about.

It's much easier to talk about the making of these than it is the use of them. So we move from something that's available in antique stores or lots of museums, to a painting which is a singular thing. This one, Erastus Salisbury Field’s Joseph Moore and His Family, about 1839 it was done by Field, is that we can see the Hitchcock chairs in the painting.

So paintings are a good iconographic source of, okay, there are these things made, they now sit in museum collections or private collections. But did anyone care? Did anyone use them? And then second, how did they use them? What kinds of rooms did they appear in? Did they appear in porches, as porch furniture? Did they appear as kitchen seats? Or in this case, did they appear in the parlor, the fanciest room of a house?

So, here we have interestingly enough, there's a family of four children, two adults. Everyone is in black, white and black. The father and the mother are sitting in these Hitchcock chairs. They're very brightly—we can see the cornucopia on Joseph's chair along with the striping on the legs that peers out, so this gives you a sense of the vibrancy when these were new.

There's stenciling on the stand right behind the family. In that case, the stenciling is used along with the mirror that's above them to give the imitation of mahogany, of richer wood. So stenciling can be used also as a means of imitation. So there's lots of this faux décor going on.

Because, again, these middling people are looking on one hand to establish a connection to sort of what was once previously luxurious goods, and so they are using, just like the portrait itself, something that used to be beyond the reach of a middling family.

This is a family dressed in their best. This is not an ordinary experience. This was an exceptional experience.

So we often need to look at, what are the moments in a family's lifecycle when a portrait might be made? Marriage. Death. Addition to the family. So again, these are exceptional moments, and we can sort of trace out the lifecycle.

So, this is in some ways like an inventory. It's an inventory of all the nice things that they've acquired, and actually some of these objects that Elmira's holding in her hand, some of the furniture, these two chairs, are actually passed down from the family with the portrait and exist in the same collection at the Museum of Fine Arts. So, we always sort of wonder about that. Are these things sort of like that the portraitist brought in and gave to the family so they could look fancier? Or actually are they their real possessions? Are they their real clothes? So, here we have I think, the jewelry that she's wearing, has passed along in the family collection, so we know that these adornments are theirs.

And then, I think with students it's really fun to work from, what do you see? What are the different things you see? And I think students can do a good job with that to, what do you think they're used for?

What does it mean? What did this portrait mean to the family that commissioned it? What did it mean to the family that displayed it?

This thing is almost six feet wide. It fills a whole wall at the Museum of Fine Arts. You wouldn't know that from this. It could easily be a miniatu&8212;you know, small. So, that's something you really want to sort of make sure that's in there because something that's six feet would take a lot more time, a lot more money.

Now, what's of course most interesting about this one is its title, "Across the Continent, Westward Course of Empire Takes Its Way." It has all the elements, all the stereotypical elements, of the sort of westward movement. We actually know the engraver, Frances Flora Bond Palmer, she’s a—Fanny Palmer as she was called. She's the most famous Currier & Ives employee, and also was a painter in her own right, as a British immigrant.

When I look at it, I see most—first of all a diagonal. It cuts across the image. And what cuts it across is the railroad. The railroad moves from east to west, from one corner to the other corner, as far as the eye can see, the rails go to this sort of featureless line that is the future.

On one side of the diagonal I see a natural scene. It's a heavily constructed natural scene, but nonetheless it is nature. It has a beautiful series of lakes or waterways that move up to a set of Rockies or whatever. Trees as far as one can see along with more of a prairie landscape.

But, right next to the railroad on the immediate foreground are two Native Americans on horses. They are part of the natural world, which again is a stereotype. Sitting on their horses with their spears pointed, or lances, sort of looking somewhat forlorn. In fact, the plumes of smoke from the railway go in their direction, pretty much sort of cover them. So there is a certain element of disrespect going on, that they are being left in the traces of the railway, left behind.

So that is the past. On the other side of the diagonal is a very different scene. This is civilization. This is a cluster of log cabins in the foreground. One in the foremost—closest to us, is a log cabin with a sign emblazoned on it, "Public School." What is more typical, stands in for civilization for these pioneers, is the public school. The engine of progress. The engine of civilization. Whatever community wanted to set up to proclaim that they were connected, you know, to their past and to their future.

So, the railway sort of cuts across. There are people watching, well dressed, sort of watching the railway. There are men all the way on the left that are hacking out, cutting down, trees. So again, it has this 19th-century—the emblem of progress is stripping away the forest, cutting down the trees. The more stumps, the better. This is not an ecological consciousness; this is a progressive consciousness.

And the fact that it's so stereotypical makes it wonderful to use, because it lays out the formulas. It's expansive in its meaning, and thousands of these were made, and thousands of these went up in people's homes on their walls, framed. So it really has the element of sort of mass produced, mass marketed, even though it's made by hand in many of its elements, and distributed widely, and really speaks for these tropes of American memory. What the past is, but more importantly, what the future might be.

The trick I think, with the Fanny Palmer, is of course to teach this as a heavily symbolic image made by an Eastern establishment, rather than a representation of pioneer activity. Almost all the images we have of the West, and this goes through the 19th-century Frederick Remington or others, are made by Easterners. And that's a question itself. So, was this something that—you know, why would someone have wanted to own this? Even better yet, what would someone think about going west if they saw this? Would this make it attractive? Probably, yes, actually, because the Indians are off on one side, civilization's on the other. There are public schools. This looks like, you know, real progress is going on. It's a fairly safe environment.

Now, when we read women's letters at the same time, from the Illinois prairie or from the Oregon or whatever, we often get much more discordant notes about isolation. So, instead of the social thickness of ties here that are easily reproducible and make it attractive for men and women, these women write about the fact that they've lost their friends. Nearest settlement is—nearest farmhouse is three miles away. And maybe only on Sundays, or the men go into town to do business, but they stay home with their ever-increasing family.