According to the National Museum of the American Indian's website, the museum strives to advance, "knowledge and understanding of the Native cultures of the Western Hemisphere, past, present, and future, through partnership with Native people and others. The museum works to support the continuance of culture, traditional values, and transitions in contemporary Native life."

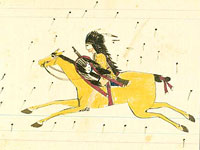

There are two sections of the NMAI website which are optimal for educational use. First, is the museum's collection of print resources, designed with educators in mind. These include study guides, posters for your classroom, museum guides, and lesson plans. The other must-see section consists of the museum's more than 30 online exhibits, ranging from horses in Native American culture to how native traditions fared after European contact.

If you're specifically interested in planning for the holidays, be sure to check out the museum's study guide, selections of the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address, poster, and list of activities on Native American perspectives concerning Thanksgiving.

The museum also offers several audio resources. See how something we view as so definite—time—is actually cultural, by exploring Native American chronological perspectives. You can also use the site's list of radio and film networks to help you research available Native American media.

Visit Indigenous Geography for a wide variety of Native American perspectives on the environment. The site also offers introductory lessons in multiculturalism and curriculum guides for each community presented.

Luckily, for teachers who are interested in visiting the museum in person, there are two locations—DC and New York City, with the archives at yet another site, Suitland, MD. School visits are welcome. If you are considering visiting the New York museum, consider arranging a cultural interpreter, to give a tour from a Native American perspective, or take a look at the upcoming student and teacher workshops.