Teaser

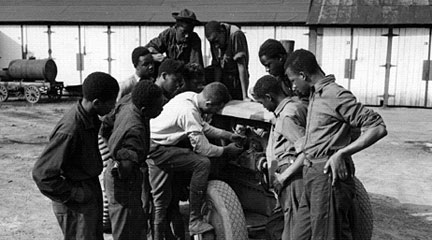

Examine the role of African Americans in the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Great Depression.

Description

Students engage in a sophisticated exploration of the African American experience with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) during the Great Depression.

Article Body

The strength of this 2–4 day lesson is that it presents students with primary source documents representing multiple perspectives. These documents can help build students' understanding of the issues surrounding African American employment in the CCC. The documents also provide an excellent platform for students to explore the sticky political and civil rights issues facing the Roosevelt administration as it attempted to hold together a precarious political coalition that included both large numbers of African Americans and conservative Southern Democrats opposed to civil rights reforms. The lesson is comprised of four activities. Each activity is well structured and provides detailed procedures for classroom teachers. Teachers will use class discussions to assess student learning. The lesson closes with a solid writing prompt that encourages students to use documentary evidence to construct a historical argument. The lesson plan does not, however, provide resources for teachers to help students construct a high-quality historical essay. We suspect that teachers may need to provide guidance and assistance for writing the essay beyond that which is described in the lesson.

Topic

Civilian Conservation Corps; New Deal, Civil Rights

Rubric_Content_Accurate_Scholarship

Yes Historical background is detailed and accurate. Most documents are from the American Memory collection of the Library of Congress.

Rubric_Content_Historical_Background

Rubric_Content_Read_Write

Yes Lesson centers on reading and interpreting documents. It ends with a writing assignment that requires students to use textual evidence to support their answers.

Rubric_Analytical_Construct_Interpretations

Yes Students use evidence from primary documents to build understanding of the African American Experience in the CCC and its political and social ramifications.

Rubric_Analytical_Close_Reading_Sourcing

Yes Guiding questions require close reading of both source and perspective.

Rubric_Scaffolding_Appropriate

Yes Appropriate for 9–12 U.S. history classrooms. Could be adapted for higher-level middle school classrooms.

Rubric_Scaffolding_Supports_Historical_Thinking

Yes Activities 1, 2, and 3 include excellent guided questions for use in class discussion or small group exploration. Activity 3 provides strategies to help students analyze a primary document.

Rubric_Structure_Assessment

No Assessment is conducted primarily through class discussion. However, a final essay question encourages students to use historical evidence. No evaluation criteria are included.

Rubric_Structure_Realistic

Yes Activities are clear and explicit. Of course, teachers may need to adapt the lesson to meet student needs. Lesson presents teachers with the option to use electronic tools to help manage documents and student work if they set up a free user account.

Rubric_Structure_Learning_Goals

Yes The four activities are well structured and the activities progress logically.

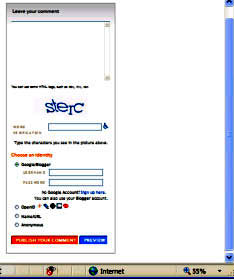

The screenshot above shows what appears after a student clicks on the comment link. To leave a comment, the students type in the comment box, insert the word verification, and then choose their identity (assigned by the teacher). As the creator of the blog, you will be able to edit and remove any comments that you deem inappropriate.

The screenshot above shows what appears after a student clicks on the comment link. To leave a comment, the students type in the comment box, insert the word verification, and then choose their identity (assigned by the teacher). As the creator of the blog, you will be able to edit and remove any comments that you deem inappropriate.