My project was to write a history of the election of 1932, which is an election that everybody figured they all knew, it was a forgone conclusion that because of the Great Depression, Franklin Roosevelt was going to be elected president. In fact, many accounts reduced the election of 1932 to a single sentence, "The Depression elected Franklin Roosevelt president." So the question is, how do you write a book about something everyone else can write off in a single sentence? I came to the conclusion that people read backwards into history, we know how history ends and we have 20/20 hindsight and we make assumptions from the end. But those who lived through it didn't see the end first, they started at the beginning and they worked their way to the end, much of which was very problematic.

The thing that surprised me when I read the sources was that Herbert Hoover thought he was going to win reelection in 1932, and there were a lot of very good, very competent political commentators who thought he had a very good chance of doing that. Actually, statistically if you look at what was happening in early 1932 there was an upswing in the economy. About a million people went back to work, and business was beginning to move again. Hoover thought that if that continued until November of 1932 he would be reelected; it was not a bad assumption in a lot of ways. He thought he could run the traditional 'rose garden' campaign the presidents did in those days. Which [meant] they stayed in the White House and they made official proclamations and they let their cabinet go out and campaign for them. Calvin Coolidge did that in 1924, and it was seen to be unseemly for presidents to get in a train and go around the country and pitch for themselves. So Hoover played a very low-keyed campaign from the time of his nomination in June throughout the summer.

A couple of things happened to change all of his expectations. One was the reason why the economy was coming back was because the Federal Reserve had loosened up on credit in early 1932. And the reason they did that was because Congress, which was in panic over the Depression, was pushing for inflationary solutions—lots of government spending, let's get money into circulation, let's get people back, let's hire people to work and there were all sorts of federal emergency relief programs that were being proposed in Congress. So the Federal Reserve to steer Congress out of that loosened up credit and things were going fine.

Well, in the summer of 1932, Congress adjourned—they went home—which they did, they usually worked for six months of the year and then they were gone for six months a year. The Federal Reserve sort of breathed a great sigh of relief and tightened back up on credit, under the old orthodox financial system they were trying to balance the budget. One way to do this is to tighten up on credit. Well, the economy went into a tailspin, the million people who had gone back to work at the beginning of the year had all lost their jobs, plus more by the end of the year. In fact, the economy went into a total tailspin, even after the election until March of 1933 when Roosevelt was finally inaugurated.

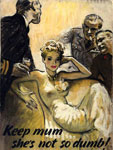

This is happening in the summer and the fall and it takes a while for Hoover to recognize what the public mood really is. The turning point is the main elections in September, and that's what this cartoon by Clifford Berryman—which ran in the Washington Star—depicts. Clifford Berryman was a cartoonist most famous for creating the teddy bear. When Theodore Roosevelt was president he—Theodore Roosevelt—refused to shoot a small bear on a hunting trip and so Berryman created a cartoon about this and the small teddy bear became very popular as a children's toy and that became Berryman's symbol for the rest of his career. He was still drawing cartoons when Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman and I think Eisenhower were president; his son then took over drawing the cartoons and continued to draw them until Nixon was president. All of those cartoons have been given to the National Archives and they're in the Center for Legislative Archives.

So as I was getting ready to write my book, I contacted the National Archives and I said, "What Berryman cartoons are available for the election of 1932?" One thing you're looking for, of course, are sources that you can use that are not copyrighted, and the Berryman cartoons are all public domain. So, the Archives gave me about a half a dozen cartoons from that election; I wound up using two in the book. This one I used because I thought it captured the moment when the Republicans knew they were in trouble and when Hoover realized that he was in trouble.

Now Maine, because of the weather, always held its state elections in September before the snows came. That was considered to be a barometer of what public opinion was. There was an old slogan, going back to the Civil War, "As Maine goes, so goes the Union." Maine tended to vote Republican—actually since the end of the Civil War—the Republicans were the majority party; so therefore, whatever Maine voted did tend to reflect what was going on. Also, in those days the Republican Party's base really was in New England and in the Midwest. So a Republican president candidate was probably never going to get an electoral vote in the South, not as many in the West—it's up for grabs, the West was a contested area. But Republicans from McKinley on counted that they were going to carry the Midwest and they were going to carry New England and the Northeastern states.

Hoover figured that, even though he had done fairly well in the South in 1928, he probably was not going to do very well there in 1932. The reason he did so well in 1928 was that he was running against the first Catholic candidate, there was huge anti-Catholic sentiment in the South—Al Smith did very poorly in the South, Hoover did very well. But that was not an issue in 1932. Then he thought that the West was sort of radical and he probably wouldn't carry much of the West, but that he would carry New England and Northeastern states.

So when Maine went Democratic in September of 1932, when they elected a Democratic governor and Democratic members of the House of Representatives everybody was shocked. When Franklin Roosevelt was campaigning—the news came as he was campaigning—and everybody in the stands yelled, "As Maine goes so goes the Union!" meaning you're going to do this, Maine has already voted Democratic. In fact, John Nance Garner, who was the vice presidential candidate for Roosevelt told the crowd, "Maine's already voted Democratic, you might as well make it unanimous." So that became a slogan, it boosted Roosevelt's spirits and added to his crowds that he was getting.

It shocked Hoover, and Berryman captured this perfectly, I thought, in this cartoon. The Republican elephant—and the elephant was the symbol of the Republican party going back to the days of Thomas Nast and the Civil War era—is obviously ill, in a terrible funk with a cloud over its head.

It has several nurses; one of the nurses is Vice President Curtis. Charles Curtis had been majority leader of the Senate, he was vice president but he was not Hoover's choice for vice president, he was sort of thrust on Hoover by the Republican convention. Hoover referred to him always as the "Old Gentleman," had very little to do with him; in fact, during Hoover's presidency there was a George Gershwin play called Of Thee We Sing, and there's a vice president in the play who's modeled after Curtis who can only get into the White House on public tours. So this is Charles Curtis, well, Curtis is this solicitous nurse taking care of the elephant.

Also Everett Sanders, who's the chairman of the Republican National Committee, is the other nurse fretting over this. And "Doctor" Hoover is saying, well, we're going to have to do something to—you know, give some new medication, we've got to get this patient back on his feet because this is the first omen of tough times coming up in this election.

In fact, one of the sources that I used most heavily for this project was the diary of Hoover's press secretary, a man named Ted Joslin. Joslin wrote a little page everyday while he was Press Secretary and in his book—in his little notes—Hoover says, "This is a disaster for us" when he gets the results. "We are going to have to change our tactics, we're going to have to campaign vigorously." Hoover realizes the rose garden campaign is out, he's got to raise a lot of money, and he's got to get out on the campaign hustings and he's got to campaign. From that point on, Hoover changes course and does become a very active candidate in October. It's almost too late for him at that stage.

But this cartoon captures that moment. And I think in that sense, for students coming to the project, it personalizes it a little bit, it shows them the urgency and it's also a humorous account of the period. That’s one of the great things about editorial cartoons in general, that visual depiction with a bit of humor. And in the case of Berryman of course the faces are all very close to what the people actually look like, it's just that the bodies have been twisted around to make them a little bit funnier and [he's] dressed them up as nurses and doctors at that point.

One of the things that editorial cartoonists like to do is put people into funny costumes. It's very common in the late 19th, early 20th century for them to dress men as women. For instance presidential candidates are all going to Cinderella's ball, which one is going to be—who are the ugly stepsisters and who's going to be the "Cinderella" at the ball. Of course these were bearded men dressed up in frilly frocks and all the rest of it to make it a little bit funnier and to bring them all down to size a bit. In this case Curtis and Sanders were not particularly dynamic figures so it's sort of making fun of them to turn them into nurses.

Women were not major political players, they were just getting into it because starting in 1920 women got the right to vote. A lot of women didn't use the right to vote actually at that period; there were a few women who were elected to office, not many. In 1932 there was a women candidate for the Senate in Illinois and she's defeated. Really it takes a while for women candidates to take over. So politics is still "men's business," but the cartoonists still turn the men into female figures.

Now, "Doctor" Hoover is dressed as a man. Hoover ran his administration, he was in charge, nobody would have put Hoover in a nurse's costume. He was the doctor. He had been seen actually before this as the nation's physician. Before he became president he had been Secretary of Commerce during a major flood that took place in the Mississippi River. He was sent in to help [with] emergency relief. Before that during World War I he had provided emergency relief for the Belgians and others in Europe. So Doctor Hoover was the man who came in when you were sick and in trouble. That was the great irony of his presidency—the nation was in trouble and Doctor Hoover failed and people had expected him to play the role he had played before he had become president. For a lot of ideological reasons Hoover refused to do that. But again, an editorial cartoonist would have never gotten away with putting Herbert Hoover in a skirt in any of these cartoons.

One of the cartoonists who's very influential at this period is a man named Rollin Kirby. Kirby reported for—or drew cartoons for—the New York World, which was a liberal, Democratic newspaper; which did not survive the Depression, it went out of business in 1931, it was folded into [a] very conservative newspaper in New York. It dispersed all of its editorial writers, people like Walter Lippmann and others—and also the cartoonists—so Kirby began drawing for national syndicate, or rather having a single newspaper. His cartoons were syndicated all over the country.

When Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, went to the Chicago convention, he flew to the Chicago convention, to accept the nomination in 1932, this broke all precedent. Kirby was impressed by this and caught up with that. In the midst of Roosevelt's speech—which reporters had not gotten an advanced copy of the speech, because Roosevelt was actually putting it together as he spoke. He was taking a draft from one set of advisors and a draft by another advisor and mixing the two, as he tended to do during the campaign. There's a line in there [in which] Roosevelt promises a "New Deal" for the American people. His speechwriter had lifted this from a series of articles that was appearing in the New Republic at the time, it was a nice applause line, and it sort of reflected back to his cousin Theodore Roosevelt's Square Deal.

But Roosevelt really didn't see this as the defining description of his upcoming administration. In fact, he doesn't use the phrase for the next several speeches. It's only because Rollin Kirby, the cartoonist, drew this cartoon of a plane flying over with the words "New Deal" on it and a farmer in the field looking up at this plane going by as the symbol of "change is in the air." Newspaper editorial writers, and headline writers, and others began to realize that the New Deal was a nice little catchphrase to describe this sort of disparate notion of the types of things that Franklin Roosevelt was proposing. So Roosevelt himself later embraced the idea of the New Deal, but the editorial cartoonists were actually ahead of him in this case. That's the idea, you want to get it down to the nub, get the idea in the point it can be visual, everybody understands what it's about, makes the point, and they—in some cases—get a chuckle out of it and then they turn the page and go on to the sports.

Because the editorial cartoonists are aiming at a general public—they're not aiming at a highly educated people—they're aiming at a "man on the street" image. They want to make sure that everyone knows exactly what this is, which is the reason why they put lots of labels on to everything that they're doing so you don't make any mistakes about it. The really clever cartoonists don't need a lot of labels—the picture tells the story—but usually there's a very strong visual sense with an editorial cartoon. There are stacks and stacks of these cartoons—Berryman's at the National Archives, the Library of Congress has the Herblock cartoons from the Washington Post. It’s a huge collection, and Herblock was doing cartoons from the 1930s to up through George W. Bush's presidency.

These are terrific teaching tools; we can go back to the 19th century and use Thomas Nast cartoons. Earlier than that if you deal with the American Revolution, they have cartoons but they're so complicated and they have so many layers in labels that in many ways they overwhelm the student. But visually the cartoons become more pointed the further on you go, and certainly at least from the 1860s on they are just absolutely terrific teaching tools.

I think cartoons have changed with audiences and audience expectations. How much time people had to spend to look at these things. You know, looking at Tom Jones is a novel and the convoluted nature of those things, people enjoyed that and they could relate to that. Of course you're also talking about a much smaller reading class of people who would have looked at a magazine or a newspaper that would have carried a cartoon like this. For mass consumption, cartoons are much simpler. So for instance Benjamin Franklin draws the snake that's divided and it says "unite or die" and that's something that anybody—even the mob—will recognize and see. For the genteel drawing-room class, then you have lots of pictures that draw on religious allegories and others. You can see this change over time.

I think the late 19th century is one of the great periods for editorial cartoons. Part of this was printing needs, the artist would sketch but then it would have to be copied over by engravers. Well you have to make it a little less complicated to do that, to make the transfer. Then you had the Germans coming in, and it was a very strong German press in the United States in the late 1880s, 1890s, and on. Pulitzer and other people coming out of it, getting experience there. Hiring editorial cartoonists—people like Keppler and others—drawing originally for the German-speaking population of the United States, then translating it into English. They brought in all sorts of fanciful, fairytale, Brothers Grimm type of images into the cartoons.

They began to settle on certain very recognizable images. Nast uses the elephant for the Republicans, he's got a donkey for the Democrats—but sometimes a rooster for the Democrats, sometimes the Tammany tiger for the Democrats—but it begins to develop a lot along those lines. Uncle Sam becomes a familiar figure. Santa Claus actually was a cartoon figure that appears in the same period by the same cartoonists. So by the 1900s, the average person who picks up a newspaper can tell right away if this is a cartoon about the Republicans or the Democrats and the pictures are getting simpler and simpler.