A project of the Library of Virginia, this website makes many of the library's resources available to the public in digital form. Most resources in its digital collections relate to Virginia history, making this a treasure house for educators teaching Virginia state history.

"Digital Collections" contains the bulk of the site's content. More than 70 collections document aspects of Virginian life and politics from the colonial era to the present day, and include photographs, maps, broadsides, newspaper articles, letters, artwork, posters, official documents and records, archived political websites, and many other types of primary sources.

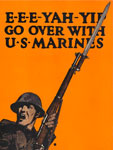

Topics include, but are far from limited to, modern Virgina politics and elections; the 2007 Virginia Tech shooting; World War II photographs; Works Project Administration oral histories; the 1939 World's Fair; World War I veterans and posters; the sinking of the Titanic; stereographs; the Richmond Planet, a 19th-century African American paper; Civil War maps; official documents related to Civil War veterans; religious petitions from 1774 to 1802; letters to the Virginia governor from 1776 to 1784; Dunmore's War; and official documents from the Revolutionary War. Collections can be browsed by topic and title, and are internally searchable using keywords and other filtering tools.

Other features on the site include the "Reading Room," "Exhibitions," and "Online Classroom." "Reading Room" lets visitors explore a primary source for each day in Virginia history or browse a timeline of Virginia history. There are eight essays on unusual sources in the library's collection as well as on new finds in the library's blog, "Out of the Box."

"Exhibitions" preserves 25 exhibits on Virginia history topics that accompany physical exhibitions at the library. "Online Classroom" orients teachers to the site with a short "Guide for Educators," suggesting possible uses for the website's resources, and offers four source analysis sheets and 30 Virginia-history-related lesson plans, all downloadable as .pdfs. The section also highlights two online exhibits designed to be particularly useful to teachers: "Shaping the Constitution," chronicling Virginians' contributions to the founding of the country, and "Union or Secession?", which uses primary sources to explore the months leading up to Virginia's secession in the Civil War.

An invaluable resource for educators covering Virginia state history, this website should also be of use to teachers covering the colonial period, the American Revolution, and the Civil War generally, among other topics.