Incorporating 20th Century US Environmental History in the 6-12 Classroom

Introduction: How to Use this Guide

Organization

- Sources are sorted into four thematic sections, arranged chronologically.

- Each section begins with an overview and index of sources.

- Primary sources are curated alongside questions, videos, and podcasts to help contextualize each source.

Links

- Many sources are linked to their hosting websites (external to this site).

Environmentalism in the Progressive Era & WWI (c. 1890-1920)

Overview

The primary source documents and videos in this section illustrate the growing environmental ethos evident in the early twentieth century, from the Progressive Era through Wold War I.

The Progressive Era, spanning roughly from 1890-1920, can be understood as a period of reform movements formed in response to rapid industrialization, urbanization, and commercialization. Among these reform movements were two early environmental movements known as preservationism and conservationism. Preservationists believed that natural landscapes should be left exactly as they were, and conservationists sought to maintain natural resources in order for them to be best used and enjoyed. John Muir was known as the most prominent preservationist, whereas Gifford Pinchot was known as the most prominent conservationist.

This growing environmental ethos continued into World War I, as Americans conserved and rationed resources in order to support the war effort. Through their participation in garden clubs and local victory gardens, American women and children on the home front used agricultural practices to support soldiers abroad.

The sources in this section exemplify the many perspectives among Americans fostering connections to the environment in the early twentieth century.

Sources

- Essay: Gifford Pinchot, 1890 (Excerpt)

- 6-12 Video: Mira Lloyd Dock: A Beautiful Crusade

- Legislative Summary of the Bill to Establish the National Park Service, 1916

- 6-12 Video: Brigadier General Charles Young

- “Everybody Plant a Garden,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 22, 1917

- “Yule Exhibits in Portsmouth,” Virginian-Pilot, December 11, 1941

- Will you have a part in Victory? 1918 Poster

- The Gardens of Victory, Poster

- Victory Gardens Video

Excerpt: Gifford Pincho Essay, 1890

Link: https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/environmental-preservation-in-the-progressive-era/sources/919

Background:

- Gifford Pinchot (1865-1946) was known as the “father of American forestry.”

- He was an influential Progressive Era conservationist who advocated for the protection of natural resources in the United States.

- This 1908 Essay discusses issues of deforestation, the over-extraction of coal and other minerals, and the negative effects of monopolies on natural resources.

- Pinchot calls for a “New Point of View” regarding the environment, and he appeals to doing so for future generations and the United States as a nation.

Discussion Questions:

- Which natural resources do you think Pinchot is referring to?

- What might Pinchot mean by a “critical point” in history?

- In what ways might this relate to industrialization?

Extension Video:

Mira Lloyd Dock: A Beautiful Crusade (Link to Web)

Annotation/Discussion Questions:

- How might Dock’s experiences growing up in an industrializing city influenced her career trajectory?

- What were some of the environmental hazards

Harrisburg faced due to industrialization? - What were some of the argument Dock made for cleaning up Harrisburg? How might her trip to Europe have influenced her arguments?

- How might public parks have helped industrializing cities?

- How might Harrisburg’s city beautiful movement have influenced movements in other cities, as well as city parks in our own time?

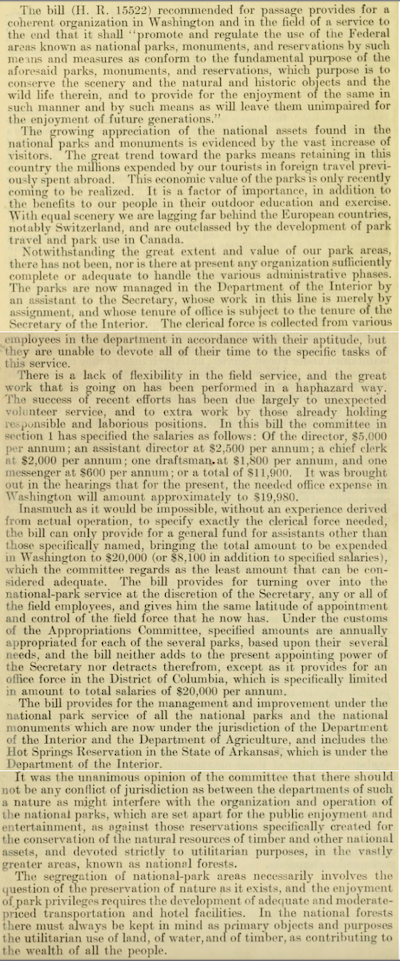

1916 Congressional bill to establish the National Park Service & NPS Video

Link: https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/environmental-preservation-in-the-progressive-era/sources/913

Background:

- President Woodrow Wilson established the NPS

into law through the 1916 “Organic Act.” - Congress proposed a bill to establish the NPS in response to the growing national ethos toward conservation coming out of the Progressive Era.

- This Congressional report summarizes the bill,

highlighting the utility behind the creation of the

NPS under the Secretary of the Interior.

Annotation/Discussion Questions:

- In the first paragraph, the report summarizes the main purposes behind the foundation

of the National Park Service. What are they? - Which department will manage the NPS? Why do you think Progressive Era Americans wanted the federal government to oversee parks? How might this fit into broader Progressive Era reforms?

- How does Congress distinguish the difference between the National Parks and the National Forests?

Extension Video:

Brigadier General Charles Young Link: https://home.nps.gov/seki/learn/historyculture/young.htm

Background:

- First Black National Park Super Intendant of Sequoia National Park

- Prolific military career despite segregation of US armed forces

Link to Supplementary Lesson Plan, NPS: https://home.nps.gov/articles/000/-h-our-history-lesson-fit-for-service-colonel-charles-young-s-protest-ride.htm

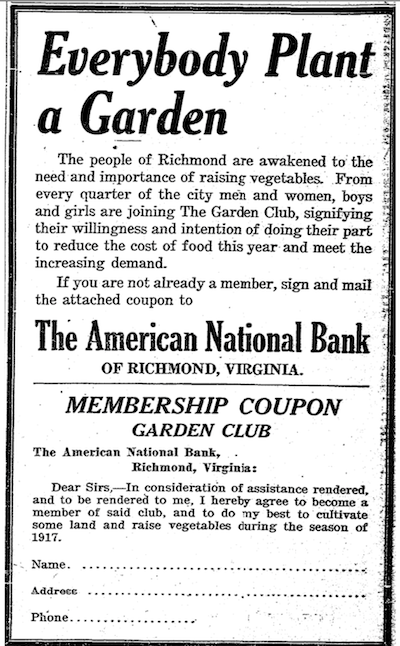

"Everybody Plant a Garden," Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 22, 1917

Annotation:

- As a newspaper, this was intended for a wide audience and was published just weeks after the US declared war on Germany during WWI. Victory Gardens were encouraged as a way to help with food shortages and rations during the war. Gardening also gave people something to do and a way to participate that would ease anxieties about the war, food, and the threat of inflation.

- While Garden Clubs were primarily run by women, men and children were also encouraged to join so the whole family could be involved.

- War took millions of men away from their jobs which included agriculture and transportation. Imports of goods from other countries including fertilizer also slowed or stopped. With decreased home grown food and decreased imports of foreign food, shortages occurred which caused increased prices and hoarding.

- The bank invested in the Garden Club in support of the war effort and the local economy.

Discussion Questions:

- Why might the Bank sponsor a Garden Club? For what reasons might the government have encouraged victory gardens?

- What benefits do you think victory gardens provided?

- What do you need to start a Victory Garden? Can everyone do it? (knowledge, tools)

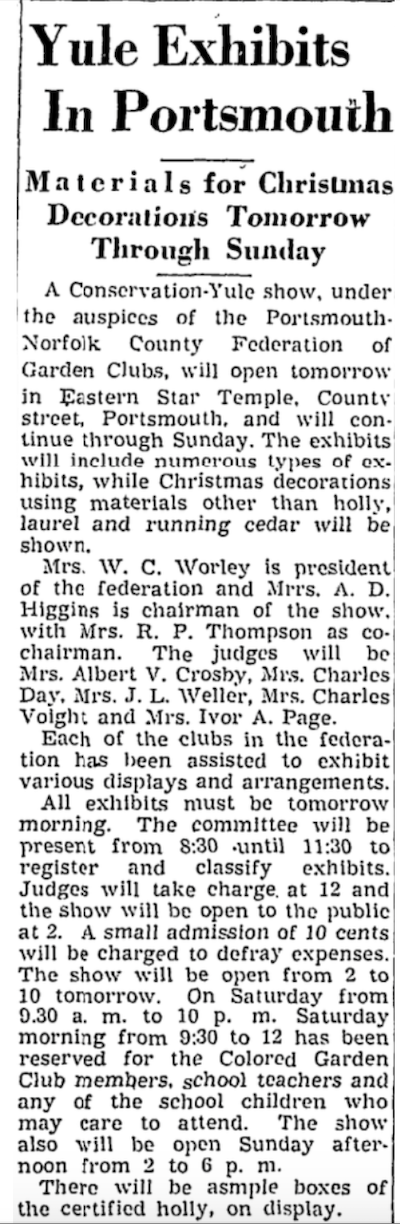

"Yule Exhibits in Portsmouth," Virginian-Pilot, December 11, 1941

Annotation:

- As a newspaper, this was intended for a wide public audience. The date reveals that this Yule Exhibit was held the weekend after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

- A Federation of Garden Clubs through the County indicates that Garden club work was important to the government. Even on the local level, there was institutional support of the war effort.

- This exhibit attempted to make conservation interesting

to a wide audience by connecting it to Christmas, and

hoped to encourage families to reduce waste and decorate using recycled materials at home. Reducing

waste was important during war time when money and

resources were scarce. - All of the club’s leaders were women which shows that

conservation was seen as a “women’s activity.” Garden

Clubs provided women leadership opportunities. Also note that they were all listed by their husbands’ names. - Garden Clubs were often made exclusive to only wealthy

white women. This article shows that in spite of

segregation, Black women organized their own Garden

Clubs and advocated for conservation.

Extension Videos:

Smithsonian Gardens: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TtrlcLslK5w

Discussion Questions:

- How might Garden Clubs connect to politics?

- Why was gardening an “acceptable” way for women to become activists and professionals?

- What were gender roles of the time? How did this work stay within or reject them?

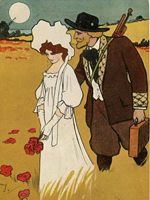

Will you have a part in Victory? 1918

Link: https://www.loc.gov/item/2002712327/

Annotation:

- This was published by the National War Garden Commission, a temporary department created to encourage gardening during WWI.

- Dressed in the American flag, this woman, beautiful and innocent looking, represents the country. She appears delicate and yet powerful, but ultimately worthy of

protection. She walks with a purpose and sows seeds that presumably will allow the nation to win the war. This imagery is often used for America or American ideals (think Statue of Liberty). The image conjures an emotional attachment to the nation, but also inspires women to join her in the garden or farm fields. - “Every Garden a Munition Plant” communicates that growing food is just as important as manufacturing guns and ammunition.

Discussion Questions:

- How is this similar to or different

from other propaganda images? - Why might America be depicted in

this way? Where have we seen

something similar? - Why do you think the painting/image

was made to look this way? - Who is the audience for this image?

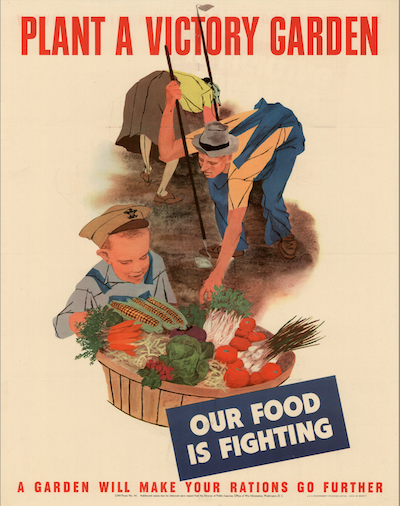

The Gardens of Victory

Gardens of Victory Video

Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uBg1ND5X3tA

Annotation:

- This film was made by the United States Office of Civil Defense. It shows the wartime need for vegetable gardens. It advertises that people can get instructions from the government on how to plant a successful garden. The film also says that people benefit from being in the sun and feeling involved in the war effort.

- In both of these sources, every member of the family is shown participating in the garden. The poster is not just focused on a wife or mother, in fact she is in the back. This family also does not appear to be wealthy which suggests Victory Gardening is for everyone.

- “Our food is fighting,” is similar to the WWI Poster that said “Every Garden, a Munitions Plant.” Food is seen as just important as military material and action.

Discussion Questions:

- Do you think this video would have been helpful to people? Why?

- What are some of the benefits victory gardens provided?

- How is this poster similar to or different from other propaganda images?

- Do you see any similarities or differences between these sources and victory garden material from WWI?

The Great Depression & The New Deal (c.1929-1945)

Overview

The sources in this section chronicle the environmental aspects of the Great Depression and the New Deal. This period can be studied for both its environmental disaster and federal initiatives toward conservation and reforestation.

In the early 1930s, as the Great Depression wreaked havoc on the economy, the Dust Bowl hit in the Great Plains and the eastern US. The Dust Bowl became known as the largest human caused environmental disaster in US history and is largely attributed to the poor use of agricultural lands as well that were intensified by a long drought in the region. The disaster would lead to mass migration from the Great Plains to Wester states, including California. Primary source photographs, an interview, and a PBS video illustrate the toll the Dust Bowl had on the environment and the people living there.

President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal ushered in a series of federally funded programs to alleviate financial burdens of the Great Depression, while also focusing on environmental projects. Notably, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) employed young men to work on conservation initiatives and reforestation projects. Their work would benefit the National Park Service, as well as State Parks around the country.

Sources

- The Dust Bowl & The Great Depression

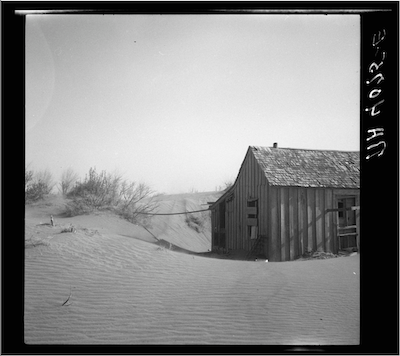

- Photo: Arthur Rothstein, “Abandoned farm in the dust bowl area, Oklahoma,” April 1936, Farm Security Administration.

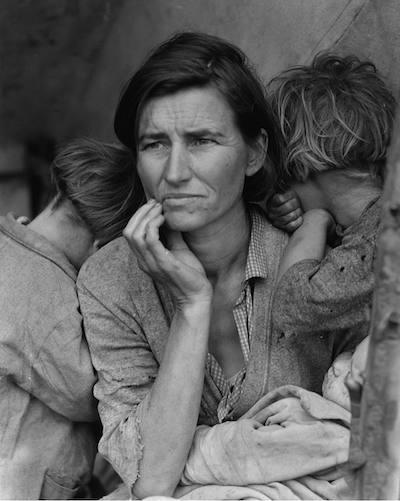

- Photo: Dorothea Lange, “Migrant Mother: Birth of an Icon,” Nipomo, 1936.

- Video: A Man-Made Ecological Disaster

- Interview with Flora Robertson, 1940

- Civilian Conservation Corps & the New Deal

- Video: Zion National Park Ranger Minute

- NPS, Civilian Conservation Corps Article

- Video: Civilian Conservation Corps | Oregon Experience, Oregon Public Broadcasting

The Dust Bowl and the Great Depression

Photographed by Arthur Rothstein of the Farm Security Administration April 1936, Library of Congress.

Background:

- In the early 1930s, extreme drought hit the Great Plains. For decades, farmers in the region had been over-plowing and depleting the soil through a lack of crop rotation.

- The drought, combined with high winds, caused massive

dust storms that blew across the plains, further stripping topsoil. - Along with environmental damage, the Dust Bowl caused

further economic hardship and health issues. - The Dust Bowl would also cause a mass migration of

farmers out of states like Oklahoma, Texas, and Arkansas

and to California as they searched for better opportunities.

Discussion Questions:

- Describe what you see in the photo.

- Read the caption:

- Who took this photo and when?

- Where is this located?

- Why do you think this photo was taken?

- Why might this photo have historical significance?

- Taken together, how do these two photographs provide different perspectives of the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression (eg. environmental, migration, childhood)

Extension Videos:

A Man-Made Ecological Disaster

Interview with Flora Robertson, 1940

Discussion Questions:

- When was this interview recorded and where is Flora located?

- How did Flora take to protect her from the dust storms?

- Why might Flora have waited to move to California?

- How does a personal account of the Dust Bowl add to your understanding of what happened?

Segregation and Jim Crow in the Environment

Overview

In the early twentieth century, Jim Crow segregation relegated Black Americans to separate and often unequal environmental spaces. In spite of this, Black Americans had robust relationships to the environment through recreation, and commercial or personal ownership.

The sources in this section highlight the specific ways outdoor spaces were segregated through law and social custom. The sources also reveal how Black Americans maintained connection to the outdoors despite the segregation they actively fought, creating spaces of joy and environmental connection for their communities. By exploring these not so distant stories, students will also be able to consider what effects of environmental segregation and racism are still present today.

Sources

- Ownership and Segregation of Beaches

- Photo: “YWCA camp for girls. Highland Beach, Maryland,”

1930, Scurlock Studio Records, Box 41, Archives Center,

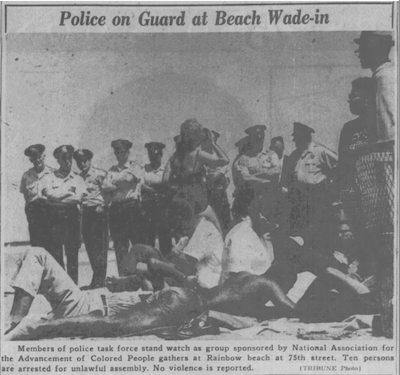

Smithsonian National Museum of American History. - Newspaper: “Police on Guard at Wade-In,” Chicago Tribune, July 9, 1961

- Video: “Five Minute Histories: Carr’s Beach,” Baltimore Heritage, August 25, 2023.

- Photo: “YWCA camp for girls. Highland Beach, Maryland,”

- “African Americans and the Great Outdoors,” National Park Service, Digital Project and Map

Ownership and Segregation of Beaches

Smithsonian National Museum of American History. https://sova.si.edu/search/ark:/65665/ep80096b07bf0a64bfb9fd5ec70b4dd9cc6

Annotation:

- Incorporated in 1922, Highland Beach was the first African American municipality in Maryland. It was also the first African American Summer Resort in the Country.

- Many very wealthy African Americans including Mary Church Terrell and Charles Douglass.

- In the late 1800s and early 1900s, most beaches and coastal properties were owned by Black people, particularly formerly enslaved folks and their descendants because the weather and sandy soil made the land less valuable. In the 20th century, predatory white land developers started trying to take these properties and monetize them as segregated beaches and resorts.

- The car and clothing hint at when this was taken, and reveal the presence of Black people in outdoor spaces, specifically beaches, long before desegregation.

- This photo is of a YWCA camp for girls. Recreation, specifically in the outdoors, was not limited to just boys.

Annotation:

- Wade-ins were just like sit-in protests happening at lunch counters during the civil rights movement. Instead of sitting down in restaurants, activists were visiting the beach and swimming in the ocean.

- Many of the beaches where wade-ins occurred, including Rainbow Beach, were not legally segregated, but were “segregated by custom,” meaning that only white people had been welcome there for many years, they were dangerous places for Black people to go.

- Wade-ins advocated for integration. Many communities ended up getting designated Black beaches rather than equal access to all beaches.

- The police are facing the group of protestors. This stance indicates that the protestors were seen as the threat of violence rather than the racist mob.

- Although no violence was reported, ten people were arrested for “unlawful assembly.” This charge is meant for people who enter a space illegally or who threaten public safety. Since there was no legal segregation of Rainbow Beach, neither one of these things was the case.

Discussion Questions:

- What or who do you see in these photos?

- When do you think these photos were taken?

- Why do you think the photos were taken?

- Did anything in the photos surprise you?

- What questions do you have for the photos?

The Environmental Movements of the 1960s and 1970s

Overview

By the 1960s, decades of industrialization, resource over-extraction, and use of harmful chemicals had taken a noticeable environmental toll. The sources in this section explore the environmental movements of the 1960s and 1970s and pieces of federal legislation passed in response to the growing popular movement to protect the environment.

By the early 1960s and 1970s, what had been a burgeoning environmental movement grew into the mainstream as activists and scholars alike noticed an intensifying environmental crisis. Some key issues included deforestation, air and water pollution, and species extinction. A few key moments in this growing environmental movement include: the fight against DDT, made popular by Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring; the first Earth Day in 1970; and the American Indian Movement’s March to Wounded Knee in 1973. Important pieces of legislation include the Wilderness Act (1964), Clean Air Act (1970), the Endangered Species Act (1973).

Sources

- "DDT is good for me-e-e," Advertisement, Time Magazine, June 30, 1947

- Podcast: "DDT: The Britney Spears of Chemicals"

- Rachel Carson, Silent Spring, excerpts

- American Experience: Rachel Carson Video

- Earth Day and March to Wounded Knee

- Walter Cronkite, Earth Day CBS News Broadcast, April 22, 1970

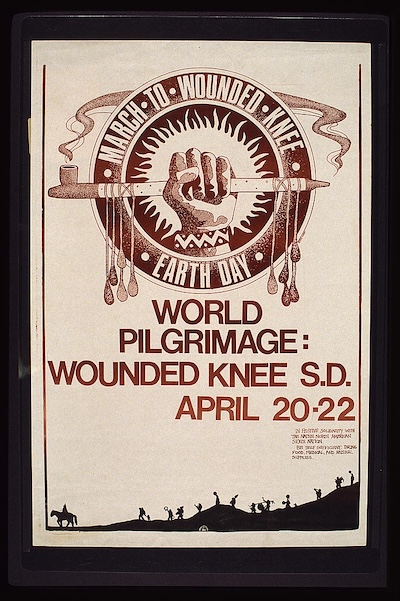

- "World Pilgrimage: Wounded Knee," Poster, April 22, 1970

- Podcast: Throughline, "The Force of Nature"

- Video: PBS, "The American Indian Movement and Wounded Knee"

- Environmental Movement: Legislation

- Complete Text of the Wilderness Act (Teaching Version)

- Endangered Species Act of 1973

- Video: PBS Learning Media, "Birth of the Clean Air Act"

- Video: US Fish and Wildlife Service, Endangered Species Act 101

"DDT is good for me-e-e," Advertisement, Time Magazine, June 30, 1947

(see https://digital.sciencehistory.org/works/1831ck18w)

Background

- Created by the Penn Salt Chemicals company

- Published in Time Magazine, June 1947

- Touts the multiple uses and benefits of DDT for different audiences, including commercial farmers and in the home.

- Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT) was developed in the late nineteenth century, but became commercially available by the 1940s.

- The US military initially used DDT to stop the spread of diseases, like malaria, that spread through insects.

- DDT became commercially available in the 1940s as a pesticide that everyday Americans and famers could use to keep insects off of crops.

- Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring has been credited with exposing the harms of DDT on human, animal, and plant health.

- The movement against DDT can be seen as one of the main signifiers of the modern environmental movement, which had already started to take shape by the early 1960.

Discussion Questions

- What kind of document is this? (Is it a newspaper article, an advertisement, a letter, etc.)

- Who created this document?

- Who might the intended audience be for this document?

- Choose three of the photographs and text blurbs. What do these sections argue?

- Taking the document as a whole, what do you think the argument of this document is?

- Given what has been discussed about DDT, how might this document be misleading?

Extend: "DDT: The Britney Spears of Chemicals" Podcast, https://digital.sciencehistory.org/works/1831ck18w.

- What were some of the initial uses of DDT?

- When did the public start to question the use of DDT and why?

- What are some of the different interpretations of when the public started doubting the use of DDT?

- How did the Polio epidemic sway public opinion on DDT?

- Where do we see discourses surrounding uses of chemicals and safety in today’s media?

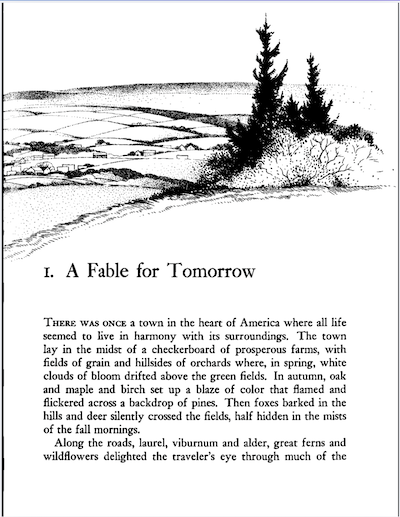

Excerpts: Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, 1962, Chapters 1 & 17

Background

- Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was published in 1962.

- Carson’s work exposed the dangers of DDT to the public, spurring an already growing environmental movement.

- Carson was born in Springdale, Pennsylvania (near Pittsburgh) in 1907, and died in 1964 after a battle with cancer.

- Carson was one of the foremost nature writers of the twentieth century.

- For more on Rachel Carson see: https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/bios/carson__rachel_louise.

Video Source: American Experience on Rachel Carson https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SeJNRaE11A0.

Questions

- Carson’s introduction spells out a “before” and “after.” How does she describe the natural landscape like before?

- How does she describe the condition of nature after?

- What is the cause of this change, according to Carson?

- Why might Carson have called her book Silent Spring?

- What is Carson’s call to action?

- How does Carson appeal to broad audiences beyond the scientific profession?

- How would you describe Carson’s philosophy behind humanity’s relationship with nature?

- Do you think Carson’s observations and solutions are still relevant today? If so, how?

The First Earth Day & March to Wounded Knee, 1970 & 1973

Walter Cronkite, Earth Day CBS News Broadcast, April 22, 1970, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WbwC281uzUs.

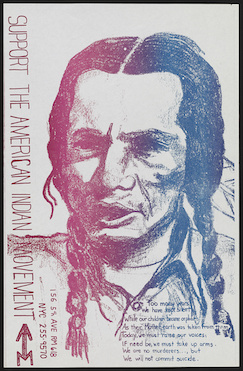

March to Wounded Knee: Earth Day World Pilgrimage Poster, 1973, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2016648085/.

Background

- The growing popular movements aimed at environmental protection led to a major moment in 1970 with the first Earth Day.

- Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin is credited with organizing the first Earth Day, wherein activists from across the country, protested the environmental degradation caused by unchecked industrial pollution.

- The American Indian Movement (AIM) used Earth Day as a focal point of the 73-day Wounded Knee occupation in 1973.

- AIM protested the US government’s broken promises and exploitation of American Indian land and human rights. Activists protested on the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre.

Cronkite Broadcast Questions

- What are some of the environmental issues Earth Day might have remedied?

- Who participated in the first Earth Day?

- Why might Cronkite have said Earth Day “failed?”

- What role do the media play in shaping public awareness and action on environmental issues?

- How do you think the environmental movement has evolved since 1970?

- In what ways do you think it has succeeded, and where do challenges remain?

March to Wounded Knee Poster Questions

- Who created this poster, and when?

- Why was this poster made?

- What is on the poster, and what might these symbols represent?

- How might the goals of Earth Day align with those of AIM?

Extension Podcast and Video

- NPR Throughline Podcast, "The Force of Nature," https://www.npr.org/2021/04/19/988747549/earth-day-1970.

- PBS Video: "The American Indian Movement at Wounded Knee," https://www.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/ush22-soc-aimwoundedknee/the-american-indian-movement-and-wounded-knee-we-shall-remain-wounded-knee/.

Environmental Movement: Legislation

Background

The growing social and cultural movements throughout the 1960s and 1970s helped push both state and federal legislatures to pass a series of laws to combat air and water pollution, and curb species extinctions. Legislation including the Clean Air Act (1963, 1970), the Wilderness Act (1964), and the Endangered Species Act (1973), provided federal support for the conservation and protection natural environment. These acts, along with the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970, formed the backbone of modern environmental policy, as the federal government began to take a more active role in environmental protection efforts.

Sources

- Complete Text of the Wilderness Act, 1964, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/wilderness/upload/W-Act_508.pdf/ .

- Endangered Species Act of 1973, https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/endangered-species-act-accessible_7.pdf/.

- PBS Video: "Birth of the Clean Air Act," https://www.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/birth-of-the-clean-air-act-video/ecosense-for-living/.

- Fish and Wildlife Service Video: "Endangered Species Act 101," https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y6wJpGO8j4Q.